Eli Broad calls his collection ‘unique in the world,’ says building ‘exceeded’ expectations

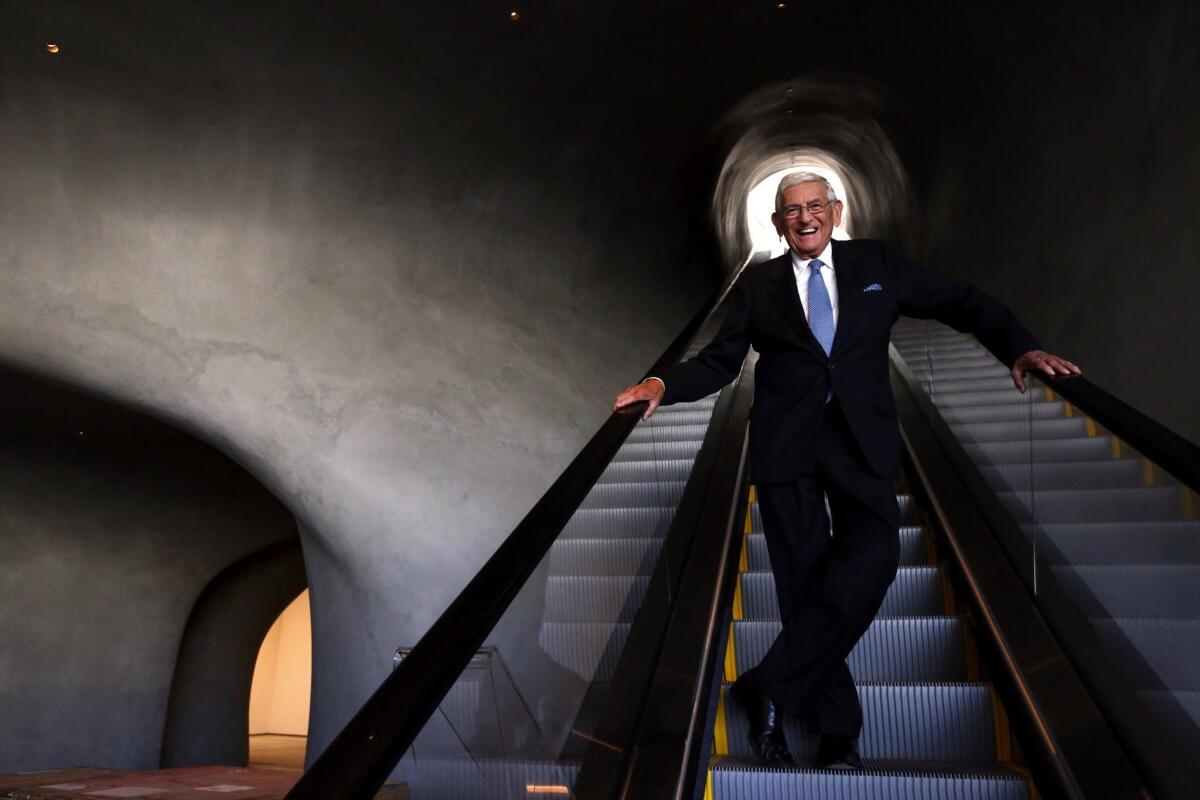

Eli Broad stands inside the Broad, a new contemporary art museum on Grand Avenue in Los Angeles on Aug. 17, 2015.

In the skewed perspective of a longtime art writer, it felt like a historic moment. After three decades of interviewing philanthropist and art collector Eli Broad about his involvement with the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and other institutions, I was going to talk to him about the museum that he and his wife, Edythe, had built for their own collection. As I entered the lobby of a Century City high rise, stepped into a private elevator and ascended to his 360-degree-view complex on the 30th floor, I reflected on dozens of past encounters — quick conversations by telephone as well as face-to-face meetings at his home and various Westside offices.

But this was different. The subject was “more personal,” as he put it. And he was up for it. Having bounced back from a series of back surgeries in time to enjoy the museum’s opening festivities, Broad, 82, was more relaxed than usual. But he isn’t one for small talk. When I told him that I had questions, he said: “Let’s get to work.”

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Broad museum: In the Sept. 13 Arts & Books section, a graphic detailing the design of the Broad in downtown Los Angeles said that all of the free, timed-admission tickets for the art museum’s Sept. 20 opening day had been distributed. A limited number of walk-up tickets will be available. —

------------

Is the museum what you envisioned when you started planning a new home for your contemporary art collection?

Yes. We had an international competition of architects and took a chance with Liz Diller. I thought her firm, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, had the best idea of what our museum ought to be. They followed the program very closely and came up with this idea of “the veil and the vault.”

So the building has measured up to your hopes and expectations?

It has exceeded them. The physical facility is second to none. The quality of the architecture is great, and it all works very well. You can’t see any other museum in the art world that has the quality of high-tech storage that we have. In the past, we had five or six different warehouses in Culver City and El Segundo. I wanted to get the collection all under one roof, other than a few things that are too big.

Private collectors have established museums around the world. What makes the Broad distinctive?

I’m very fond of the Beyeler Foundation in Basel [Switzerland, designed by Renzo Piano]. It’s a great place. The Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris [designed by Frank Gehry] is a great piece of architecture. No question about it. But we are clearly different. This all started with 40-some years of collecting and the desire to continue showing the work to the broadest possible public. We are very proud of the quality of what we have, the 2,000 works, and we wanted far more public outreach. We started with the “Un-Private Collection” series of art talks, which was a great success — 1,800 people in the audience [at the Orpheum Theatre] and more online for John Waters’ interview of Jeff Koons. We also wanted to be accessible, so we have free admission and we are easy to get to. There will be a subway portal in back of our museum. We are a more public institution than many museums that get public funds, and we think we can serve a broader audience.

What museums are peers of the Broad?

Our collection is unique in the world. We have collected artists in depth and followed them through their careers. If you think about contemporary art in the New York museums, the Museum of Modern Art has great collections, of course, but in contemporary it’s limited. You’ve got the New Museum, which is very small. You’ve got the Whitney Museum of American Art, which covers a lot of territory, going back to its founding days. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has ambitions to expand [its holdings of contemporary art], and it is taking over the Whitney’s Madison Avenue space, the Breuer Building. But as far as contemporary art goes, starting in the mid-1950s and continuing for 50 years, I can’t think of any place that’s going to have a better quality representation than ours.

In light of your long involvement with Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art and its close proximity to the Broad, how will the two institutions interact?

We are one of the best things that’s ever happened to MOCA. Why? We have a marketing budget. We are going to bring people to both museums. Admission is free at the Broad, and there will be exciting things happening. MOCA is going to benefit from all this. And we will be the beneficiary of MOCA’s being there. If people want to see great works of the 1940s and ‘50s — the Rothkos, Rauschenbergs, Klines and so on — MOCA is right across the street. And we built a very nice crosswalk.

What will the Broad mean to Los Angeles?

I think it will really help cement Los Angeles as a cultural capital of the world, together with New York, London and Paris. Those cities get 10 to 15 million tourists a year, which is a big boost to their economy. We get only about 5 million, but I think that’s beginning to change. With the amount of attention we are going to get, we will help make people want to come to Los Angeles, not only for us but for the other visual arts institutions and the performing arts.

If you add our 50,000 square feet of gallery space to MOCA and BCAM [the Broad Contemporary Art Museum at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art], I can’t think of any city in the world that has more museum gallery space for contemporary art. Los Angeles has great artists and the best art schools in the world, and there’s a whole migration of arts people coming here and more galleries opening. New York is not going away, but you don’t have to go there any more to make it.

I also feel very good about the role we have played on Grand Avenue. I’m very proud of the quality of architecture and the addition of Grand Avenue Park. When Grand Avenue is completed in two or three years, we will have a much greater population downtown. It will be fun, more lively than in the past.

When Eli Broad buys a work of art, people pay attention. How does it feel to be a force in the art market?

I think we’ve got a great reputation as having an important collection. Some people are influenced by that. Dealers, of course, use it to their advantage. But we are not a force at auctions, except when I really want something specific. Most of the things we have done started with the artists: Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat — when they weren’t icons at all. It’s almost embarrassing how little we paid for Jean-Michel’s work — $5,000, $6,000, $7,000. And to see his stuff going for $20 million! We don’t chase that.

So you don’t think you have driven up prices or played any particular role in the market?

No. In fact, I try to discourage people from buying art for investment.

In the course of your collecting, are there artworks that got away, ones you wish you had?

Of course. I don’t know where to start. But I wish we had been earlier with Andy Warhol. It took the famous show organized by Kynaston McShine at MoMA [in 1989] to really get me to understand what Warhol is all about. We have quite a collection of Andy’s work now, but I wish we had started sooner.

What will happen to your collection when you are no longer here?

It will continue. It will have the funds to continue. Perhaps not at the same intensity. The core of the collection will be from the mid-1950s and early ‘60s to now. Works and artists will be added, but we are not going to double the size of the collection. We won’t go from 2,000 to 4,000. We don’t want to be like most museums, which have things in storage that are never shown. I have a big problem with museums that do not lend and have 90% of their collections in storage, especially smaller museums.

Are your sons or other family members engaged in management or oversight of the museum?

No, they are not involved. Just Edye and me. But we have a small board of governors. The question was, who’s going to be the director? Joanne Heyler has been with me 27 years. I can’t overestimate the credit that she ought to get for all of this. People had all sorts of ideas of who ought to be the director. And I said, “You know what? I think Joanne will turn out to be a great director.” Her management skills have far exceeded anything I expected. She has assembled a great staff, quality people, and managed them very well. There’s no flash there; she’s not looking for great attention. She does a superb job. And she’s only gotten angry with me once or twice over all these years.

Did you consider not putting your name on the museum?

I sort of thought about it, but no. It’s our collection, so the name is appropriate. We started out calling it the Broad Collection and then we shortened it to the Broad.

Will your museum stand the test of time?

It will be very well endowed. We know what’s happened to the Barnes Foundation and others that were not well endowed. We are mindful of that.

How big an endowment will it take to ensure a long, healthy life for the Broad?

It will be very well endowed. Not quite the Getty, but well endowed.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.