Black composer William Grant Still drew from the blues. Forty years after his death, he still fights to be heard

William Grant Still’s ancestors were plantation slaves, working the fields of Mississippi, far from the concert stages of New York and Los Angeles, where he would rise as the preeminent African American classical composer of his day, infusing his symphonies with the sorrows and aspirations of the blues.

He played oboe, wore a thin mustache and collaborated with jazz musicians and poet Langston Hughes during the Harlem Renaissance. He was the first black person to conduct a major American orchestra when he led the Los Angeles Philharmonic in a 1936 Hollywood Bowl concert. His “Afro-American Symphony” distilled the pain and yearnings of a people brought to this land in bondage and forced to endure generations of racism.

Still’s works — lingering on the edges of a classical canon dominated by Europeans — are not often performed today. They echo with the jazz, blues and spirituals that rose from furrowed soil and oppression to define American music. In his autobiography, Still, who made a home in Los Angeles and died here in 1978, wrote that the blues “are the secular music of the American Negro and are more purely Negroid than many spirituals. They show no European influence at all.”

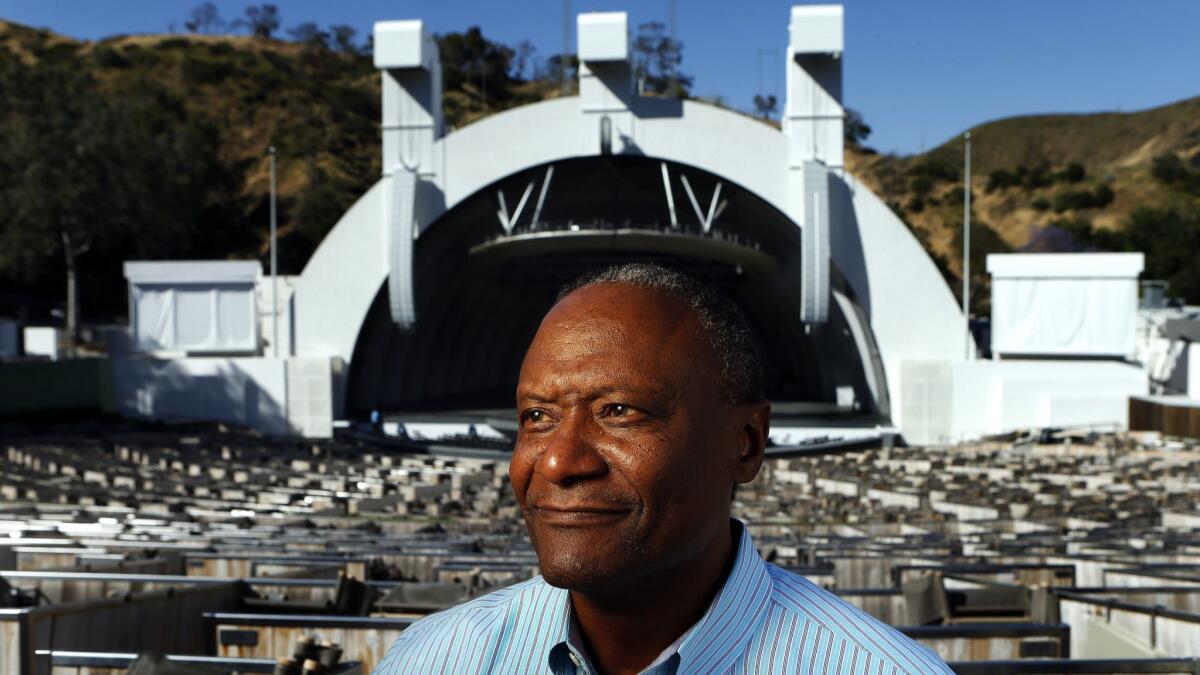

The L.A. Phil will perform the “Afro-American Symphony” on Saturday and Still’s “Symphony No. 4” on Sunday. They will be conducted by Thomas Wilkins, principal conductor of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra and music director of the Omaha Symphony. Wilkins, who is black, described Still, influenced early in his career by French-born modernist composer Edgard Varèse, as “culturally honest, unapologetic and comfortable in his own skin.”

Revisiting Still’s music today focuses attention on black composers and conductors seeking a wider influence in a field that has often overlooked minorities. It also comes at a time of troubling cultural and political tensions. Voices of recrimination rise over the nation these days as if from a crude and bitter score. President Trump’s divisive rhetoric and resurgent white supremacist fervor, including the 2017 neo-Nazi march in Charlottesville, Va., are reminders that, despite changing demographics and increasing diversity, America has yet to fully come to terms with its racist legacy.

Don’t have Negro night at the symphony or Mexican night at the symphony. Just add this repertoire to the canon.

— Thomas Wilkins, principal conductor of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra and conductor of the L.A. Phil’s programs centered on composer William Grant Still

Still endured prejudice, but he was a resilient child of schoolteachers. He believed in God and hard work and that a man’s singular abilities could lift him. But he was a realist, and like many black writers, musicians and artists of his era, he knew the sting of a slight and how the heritage and work of a race could be subsumed and reclaimed by others.

“I am waiting patiently,” he said in his autobiography, “for that man who wrote the book about how most Negro Spirituals were borrowed from White sources to come along and prove that Bach or Beethoven actually did originate them. Why not? They say that someone even proved, more than a score of years ago, that ‘ragtime’ came from Mozart’s ‘tempo rubato.’ If one has the time and the patience and a big enough ax to grind, he can prove anything.”

Still found a rich creative space in Los Angeles and his musical range was all encompassing. He scored ballets, operas and composed and arranged music for films, including “Lost Horizon” (1937) and “Pennies From Heaven” (1936). The following is an edited conversation with Wilkins about Still, race, and the prospects faced today by minority composers and conductors.

What do you find most profound in Still’s work, and what influence did the blues have on some of his compositions?

He certainly knows how to write in other styles, but he is true to his own heritage in both the “Afro-American Symphony” and the Fourth Symphony. It took me 20 years to get to that point. At first, I thought this was just folksy music, [but] the more I defend American music, the more I’m convinced that that’s OK. Certainly other composers used folk music. Dvorak. Mahler. They understood this was music that would have the largest appeal to common people. The blues and the Harlem Renaissance brought Still back to his roots. There was a certain degree of acceptance of jazz among the [musical elite]. But the blues just felt too secular, too raw, too on the nose. The blues made a lot of people uncomfortable. You were too personal with blues. I think Still’s point was, Well, so what, it is what it is and I’m not going to apologize for it.

What in particular strikes you about his “Afro-American Symphony”?

I think that’s his strongest piece. It’s the reality of the sorrow, the reality of the longing. The symphony opens with that solo plaintive English horn sound. It’s the perfect instrument to start this piece, and, then, in the last movement, there’s this aspirational, lovely song that the entire orchestra plays, and, then, he puts it in the voice of a cello, which, in my mind, is the closest instrument in that orchestra that sounds like a human voice. And then, all of a sudden, he flips the switch, and there’s a driving energy that takes us to the end of that piece as if to say this can be the possibility if you aspire to it.

Some African American composers and conductors feel they are invisible in the classical music world. What are the prospects for black composers and conductors today?

I think African American composers have more opportunity now than perhaps they’ve had in the last 30 years. They are certainly less invisible. Part of that is because of the generational shift in people making decisions, especially in the arts. We are less afraid to not solely exist in that Western European tradition. We are braver about embracing things. There’s a great canon we have that comes from that [European] tradition, but it is not correct to pursue that canon at the expense of the other. I think everybody now is braver about pursing the other as long as we don’t abandon the great canon. And that creates more possibilities for African Americans, women, Asian composers. We’re more open to a broader palette. I think we are coming to realize more keenly now, because of what’s happening the world, that we need art to speak to our common humanity more than ever.

Coming up in the classical world as an African American, what kind of prejudice and discrimination did you encounter and how did you handle it?

I can’t control what is in the heart of other people. I can only be responsible for when an opportunity presents itself to do the very best that I can. I’m sure that I have not gotten opportunities because of the color of my skin or not been hired as a music director or conductor. There’s no way for me to prove that, and I can’t spend a lot of time wallowing in that. I do have a certain degree of success. I have four jobs [he laughs], and possibly that allows me to be a little more cavalier about it. But I’m also a realist. It’s incumbent on people like me who have a degree of success to do a good job so that people don’t look at those who are coming after me — and who look like me — with a degree of suspicion in regard to intellect or ability.

Still knew the classical canon, but he also seemed to want to expand it. He knew there were other places to go. How does his work and the work of other African American or minority composers fit into this?

Don’t validate that music only in February during Black History Month. We say this about American music, period. Let’s not have 99.9% of your concerts be out of the Western European tradition and, then, one week call it an All-American program. Why not incorporate this into the regular offerings throughout the season, so it looks like you’ve taken ownership of the repertoire, not just made this mantlepiece every once in a while? Don’t have Negro night at the symphony or Mexican night at the symphony. Just add this repertoire to the canon.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

L.A. Phil: William Grant Still and the Harlem Renaissance

Saturday: 8 p.m. Thomas Wilkins conductor, Charlotte Blake Alston narrator, Aaron Diehl piano. Ellington’s “Come Sunday” from “Black, Brown and Beige,” Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” Ellington’s “Harlem” and Still’s Symphony No. 1 “Afro-American.”

Sunday: 2 p.m. Thomas Wilkins conductor, Aaron Diehl piano. Ellington’s “Three Black Kings,” Gershwin’s “Second Rhapsody,” Hailstork’s “Still Holding On” (world premiere) and Still’s Symphony No. 4, “Autochthonous.”

Where: Walt Disney Concert Hall, 111 S. Grand Ave., L.A.

Tickets: $55-$199 (subject to change)

Information: (323) 850-2000, www.laphil.com

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.