Review: L.A. Opera’s ‘Lucia di Lammermoor’ sweeps away resistance

A terrific cast, a production that enhances or at least doesn’t much get in the way, and superb conducting make Los Angeles Opera’s new production of “Lucia di Lammermoor” a go-to event.

Unveiled Saturday at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Donizetti’s hair-trigger emotional extravaganza swept away all resistance in its gorgeous bel canto flights of drama and lyricism.

In the title role, Russian soprano Albina Shagimuratova was hardly a stereotypically frail dramatic pushover. She was a dominant force, first among a cast of equals, as she reined in her power to skillfully delineate Lucia’s increasing isolation and mental decline, seeming as fresh vocally in her climactic 16-minute mad scene as she was at the beginning of the opera. Perhaps she could have gone on for another virtuosic quarter-hour. She earned the thunderous ovation she got at its end.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

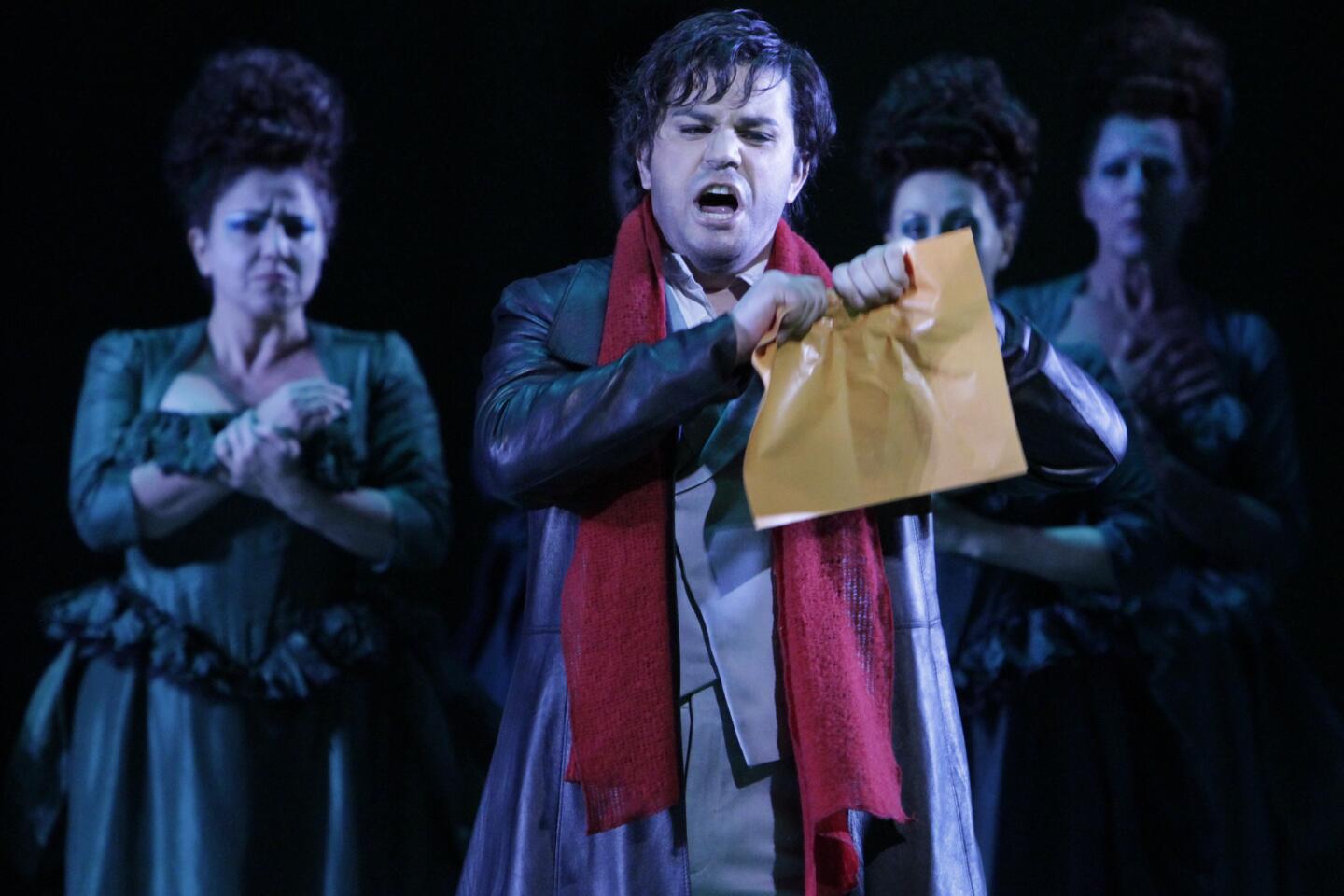

As Edgardo, her star-crossed lover, Saimir Pirgu blossomed wonderfully in the heights and rose with unflagging stamina and clarity to the cruelly high-flying lines in his death scene. The Albanian tenor acted with virile and persuasive energy, signaling in his quicksilver shifts in emotion that he, like all the principals, was a bit mad. But that’s what bel canto opera is and why we love it.

Opposing him, dynamic for dynamic and confrontation with confrontation, was Pennsylvania baritone Stephen Powell as a powerhouse Enrico, excellently even in range, and actually sensitive to the havoc he was causing his sister because of the desperate political need to save the Lammermoor line as well as, not so incidentally, his own position.

James Creswell was chilling in his vocal power as the voice-of-God chaplain, Raimondo. Creswell’s bass was burr-free and even from top to bottom. When he commanded the antagonists to put up their weapons during the wedding scene, citing Scripture, it was a Moses moment that almost exonerated the chaplain’s own role in the betrayal of Lucia.

PHOTOS: The most fascinating arts stories of 2013

Vladimir Dmitruk as the ill-fated bridegroom, Arturo, managed to basically hold his own, while Joshua Guerrero (Normanno) and D’Ana Lombard (Alisa) wisely didn’t try to compete.

In a director’s note, Elkhanah Pulitzer said she set the piece in 1885, which makes hash of Enrico’s remark that the change of succession on the throne of England (Mary following William) threatened the very survival of the Lammermoors. But maybe nobody was listening.

Pulitzer said she wanted to explore a culture in which women were controlled and marriages were arranged, as if that were not sufficiently obvious already. She got a bit heavy-handed, though, in the identical stylized dresses (by Christine Crook) and stiffly held arm postures of the women, who were roughly manipulated by dress-alike men. That presumably showed how free they were.

Admittedly, there wasn’t much a director could do with the stand-and-challenge duet between Edgardo and Enrico in the Wolf’s Crag scene (thank goodness it wasn’t cut, as it was in the bad old days), but their mere circling each other seemed routine, as did her staging of a stand-and-sing opening chorus.

Elsewhere, however, Pulitzer made effective use of dramatic shadows and lighting to show Enrico’s dominating of his sister at the beginning of Act 2, and she staged Lucia’s mad scene, with its risk-taking descent and ascent of a steeply raked series of steps, with clarity and focus.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

The projections by Wendall K. Harrington and the lighting by Duane Schuler sometimes beautifully evoked mood (consider the luscious green forest of the opening scene or the stormy sky during the Wolf Crag duet), sometimes crudely signaled it (violent red for Enrico’s angry outbursts), and sometimes perplexed (the screen-saver wandering lines between the changes in scene in Act 1). Carolina Angulo was credited as the scenery designer; Kitty McNamee was in charge of movement.

The L.A. Opera Chorus, prepared by Grant Gershon, was bold and forceful, but also, in the men’s announcement of Lucia’s imminent death to Edgardo (in one of those heaven-sent Donizetti moments), tender.

Presiding over all was conductor James Conlon, who whipped up climaxes, spun out lyrical lines and supported the singers with sensitive attention. Reverting to the original scoring, the Mad Scene incorporated a glass harmonica to illuminate Lucia’s hallucinations. Thomas Bloch intoned the spectral, eerie sounds expertly.

It was a good night for Donizetti. It was a good night for opera.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.