Review: Brilliant transformation of ‘The Magic Flute’

With its show-business staging of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” as a cheekily animated silent movie, Los Angeles Opera on Saturday night got what it very much needs. That this will be a hit goes without saying. But what this once pioneering company really needs right now is a reason to be talked about again.

So let’s talk about Barrie Kosky, one of the hot directors on the international scene and, like most hot directors on the international scene, ignored in America.

Not too many American opera companies dare hire directors who put buckets of excrement onstage, as Kosky did in a recent German production of Janácek’s “From the House of the Dead.” Don’t expect the Metropolitan Opera to call on the outspoken Australian director any time soon. In the current issue of Opera magazine, he calls the Met’s “Live in HD” “repulsive and fake,” dismissing the company’s popular movie theater broadcasts as “spectacle, schmecktacle.”

VIDEO: Backstage with ‘The Magic Flute’

Not that L.A. Opera is taking any chances with Kosky’s U.S. debut. He turns “Flute” into a dazzling live-action cartoon far too adorable to offend. Go ahead and bring the kiddies.

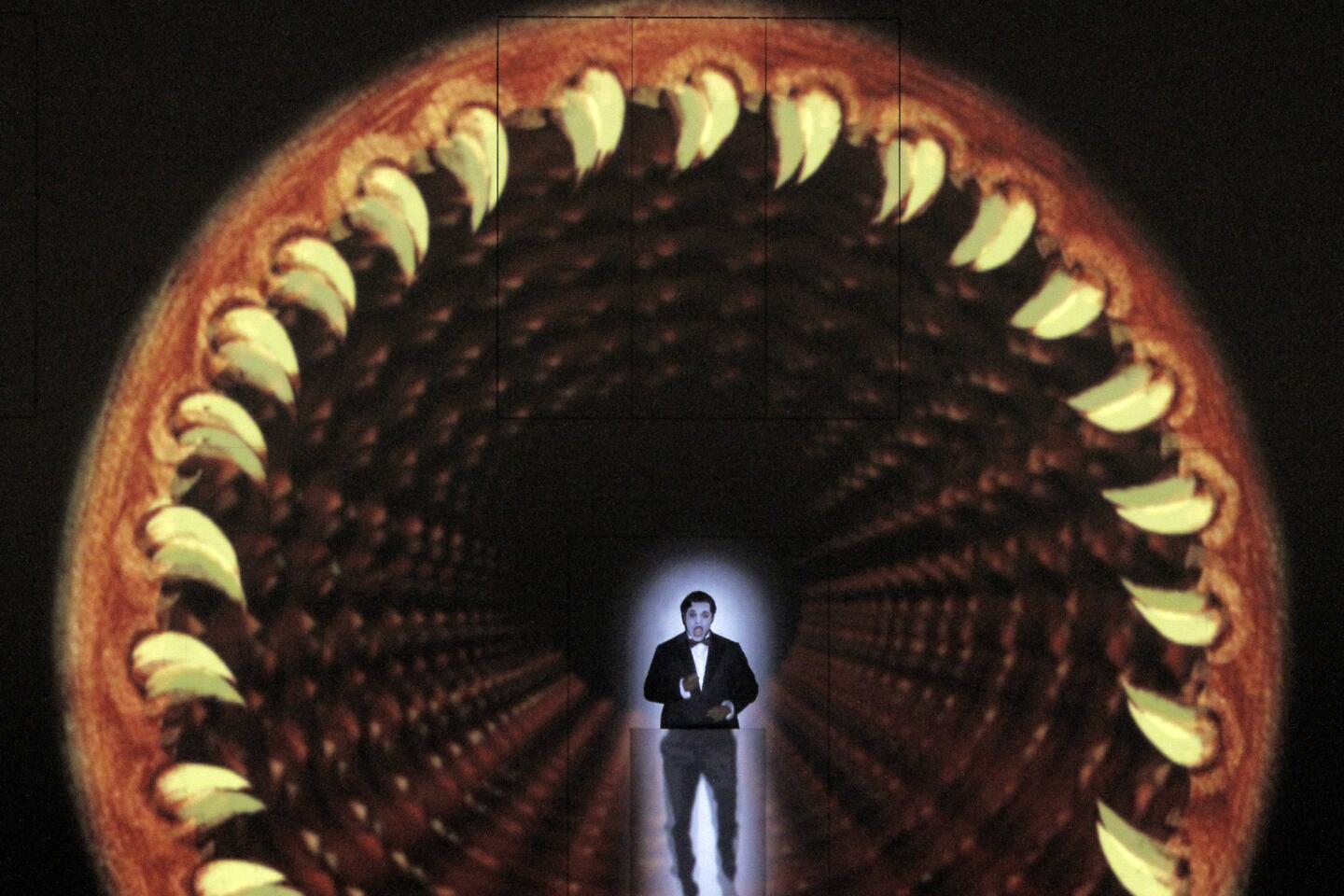

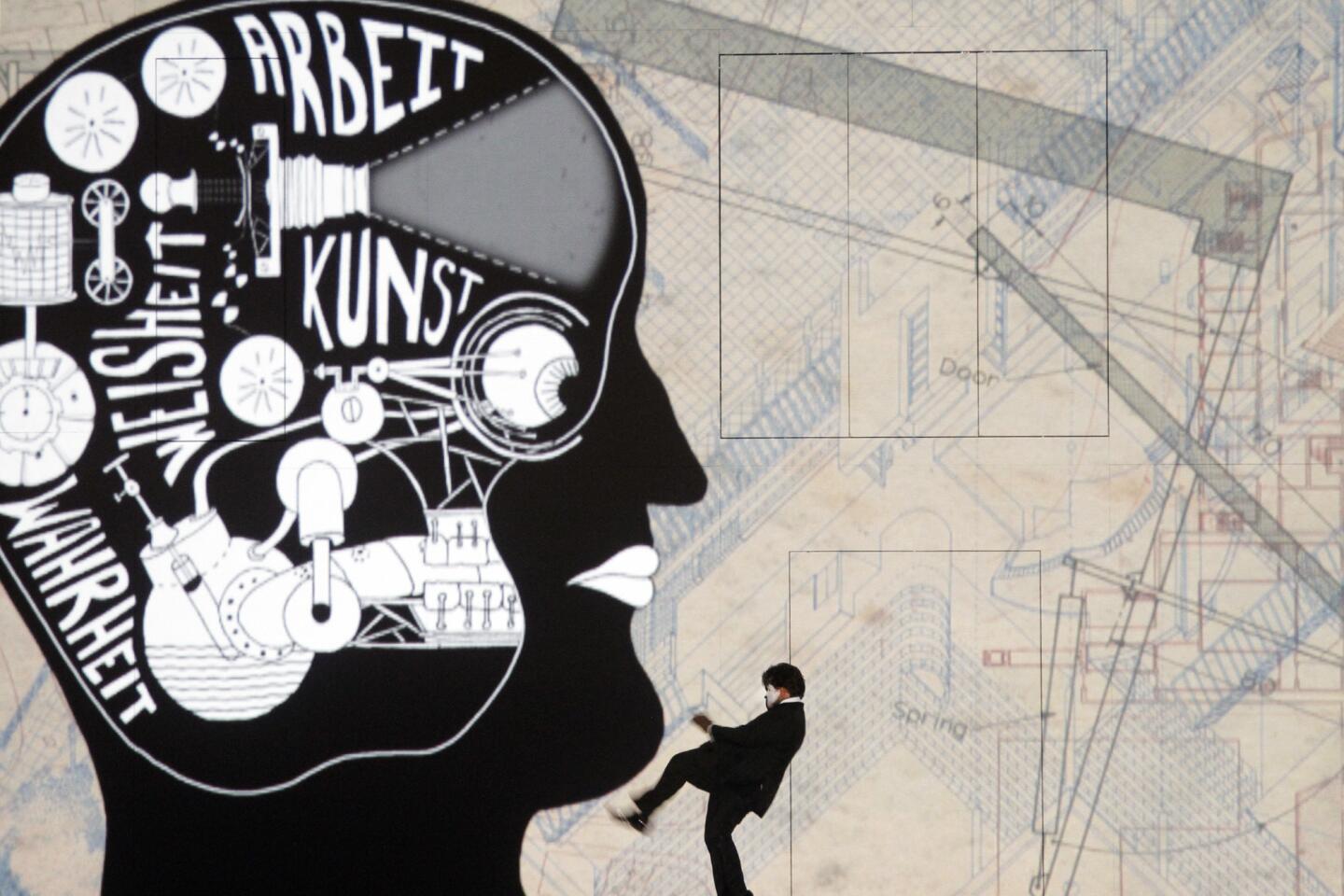

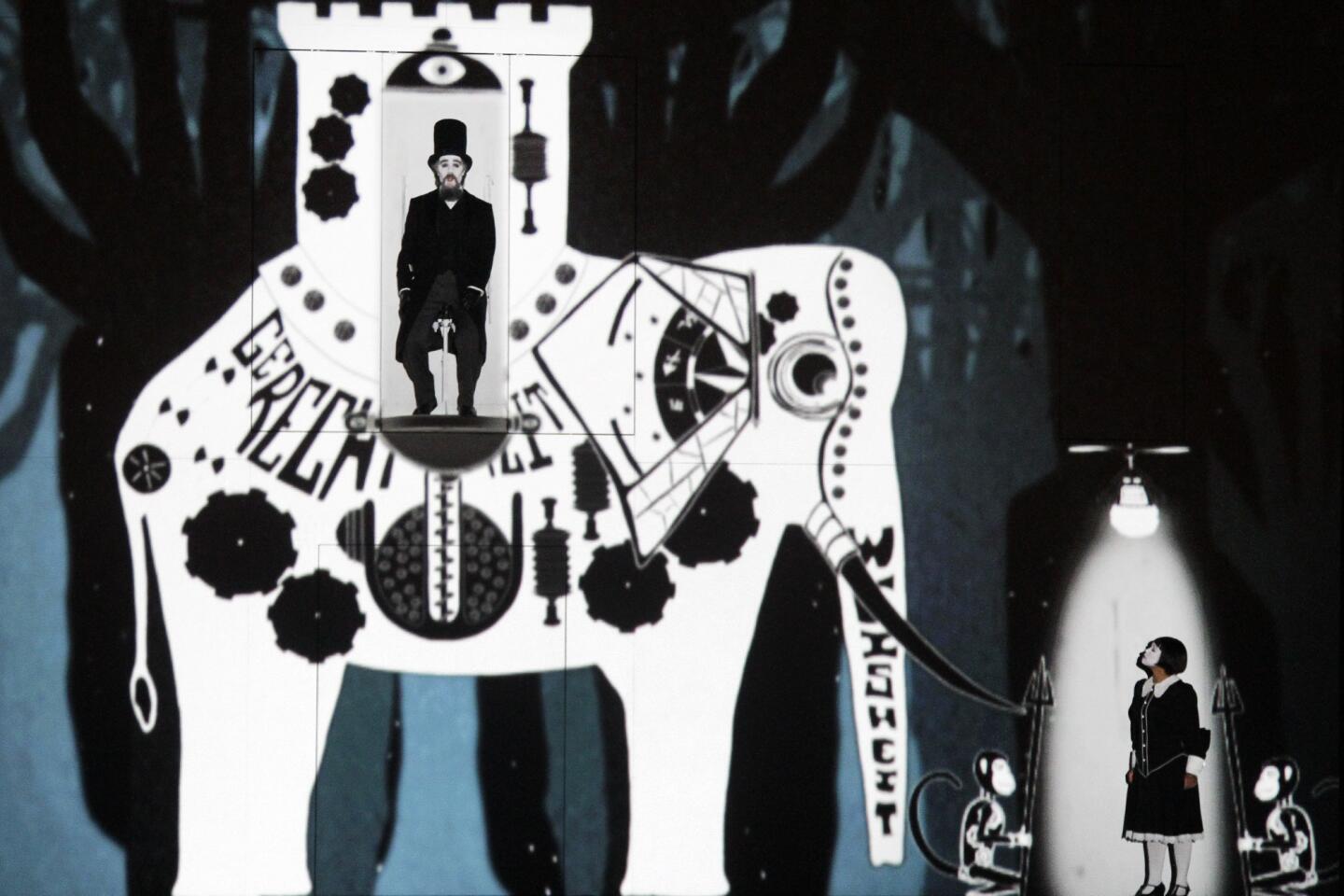

The Dorothy Chandler stage becomes a cinema. A large screen on which animation is projected has various cutout doors and platforms for the characters to pop in and out. Rather than projected opera, Met style, Kosky’s idea is projected animation as living theater. And with a cast that has effectively learned its carefully choreographed moves, the concept works brilliantly.

Attacked by a serpent at the start of the opera, Tamino really is swallowed by the beast, tumbling into a comic-book stomach, surrounded by comic-book intestines and miscellaneous yet-to-be-digested junk. The audience laughed hysterically.

PHOTOS: LA Opera’s ‘Magic Flute’

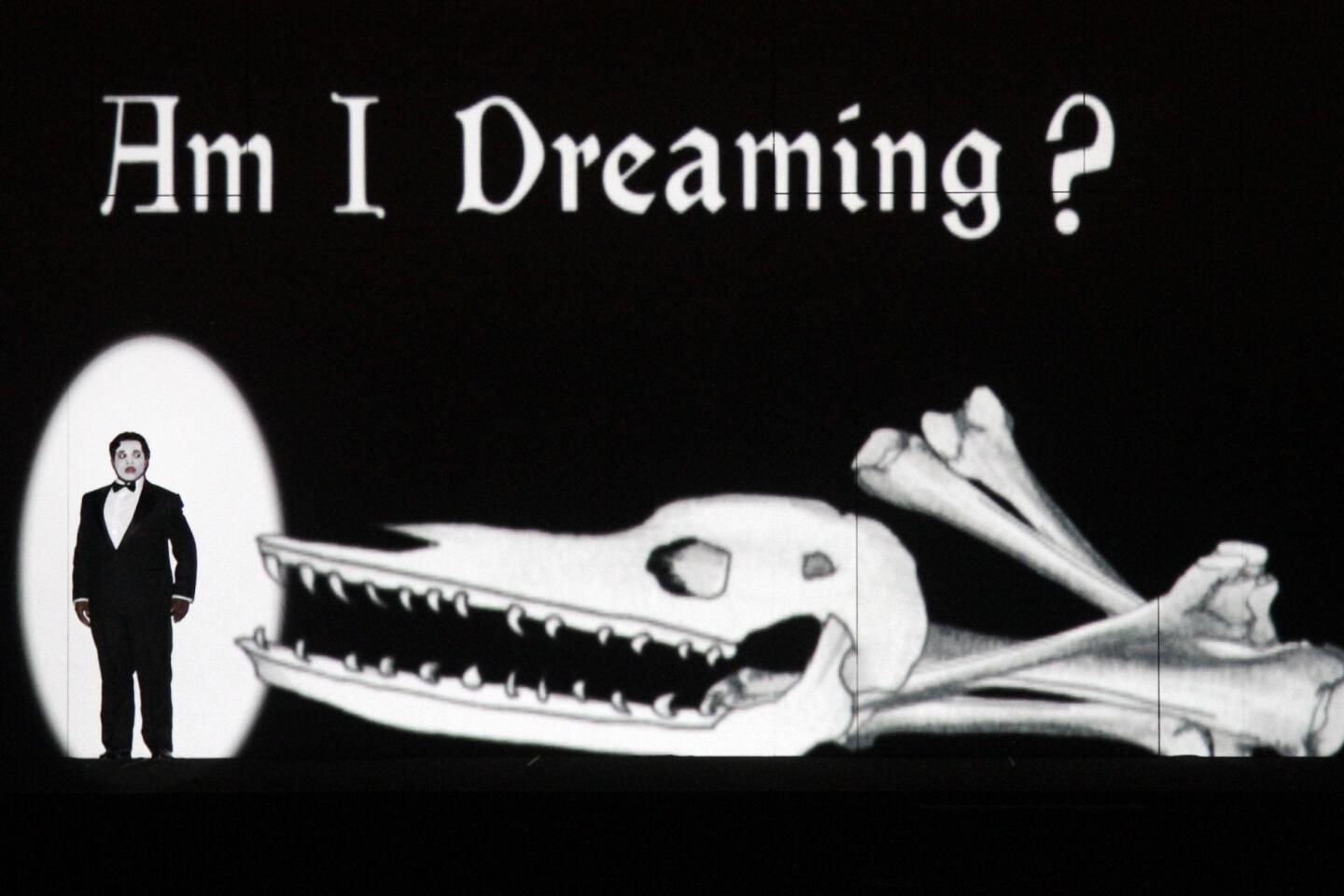

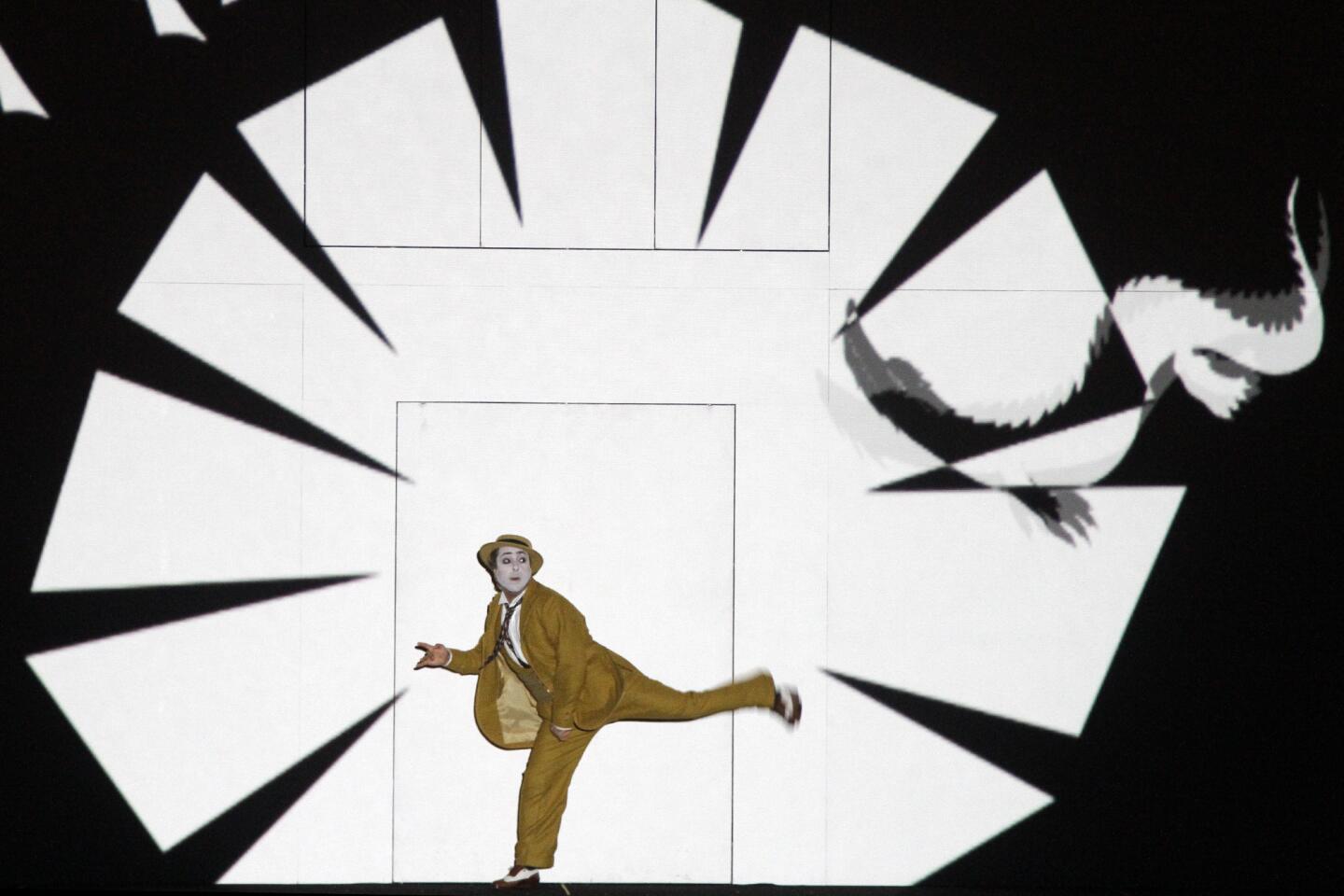

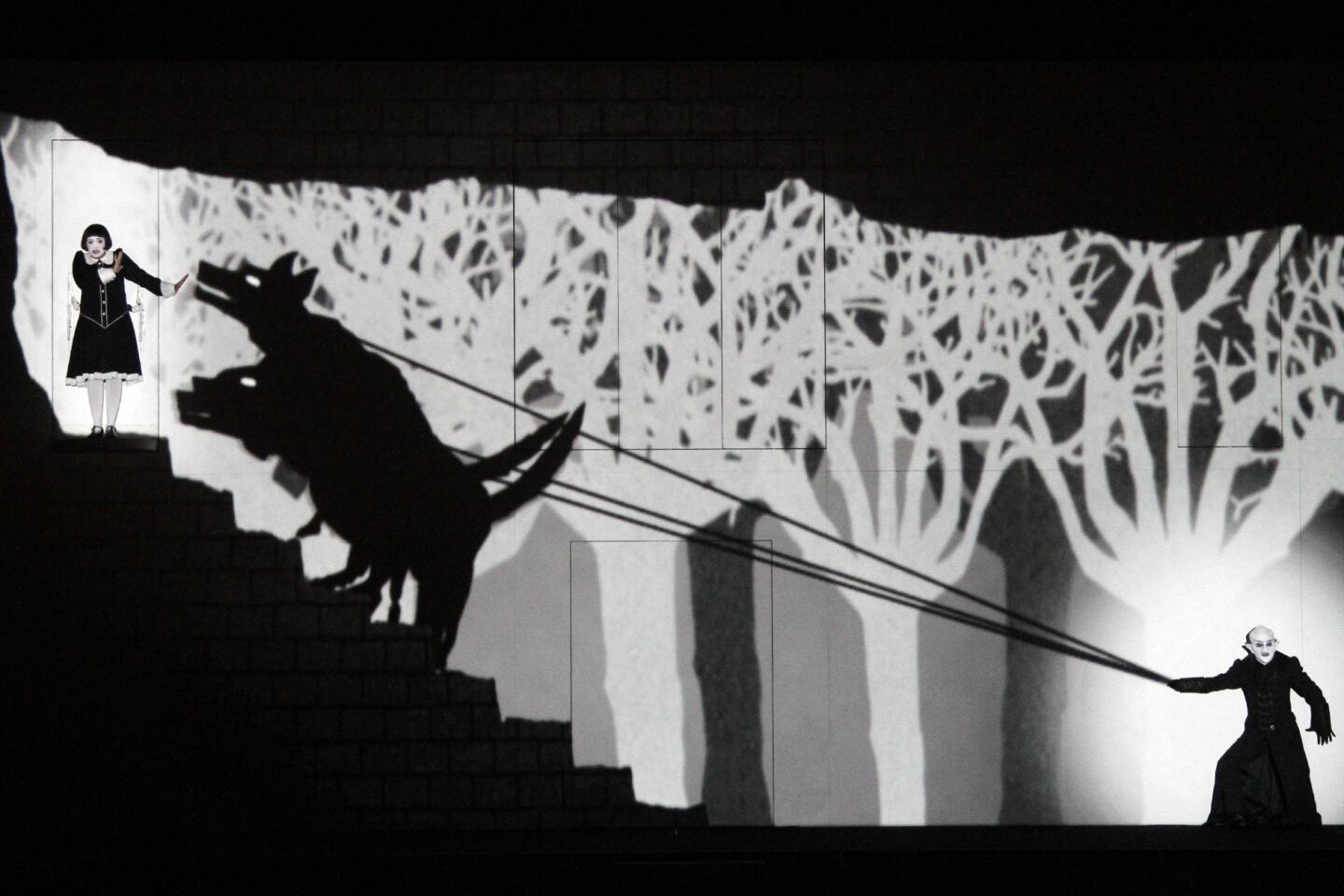

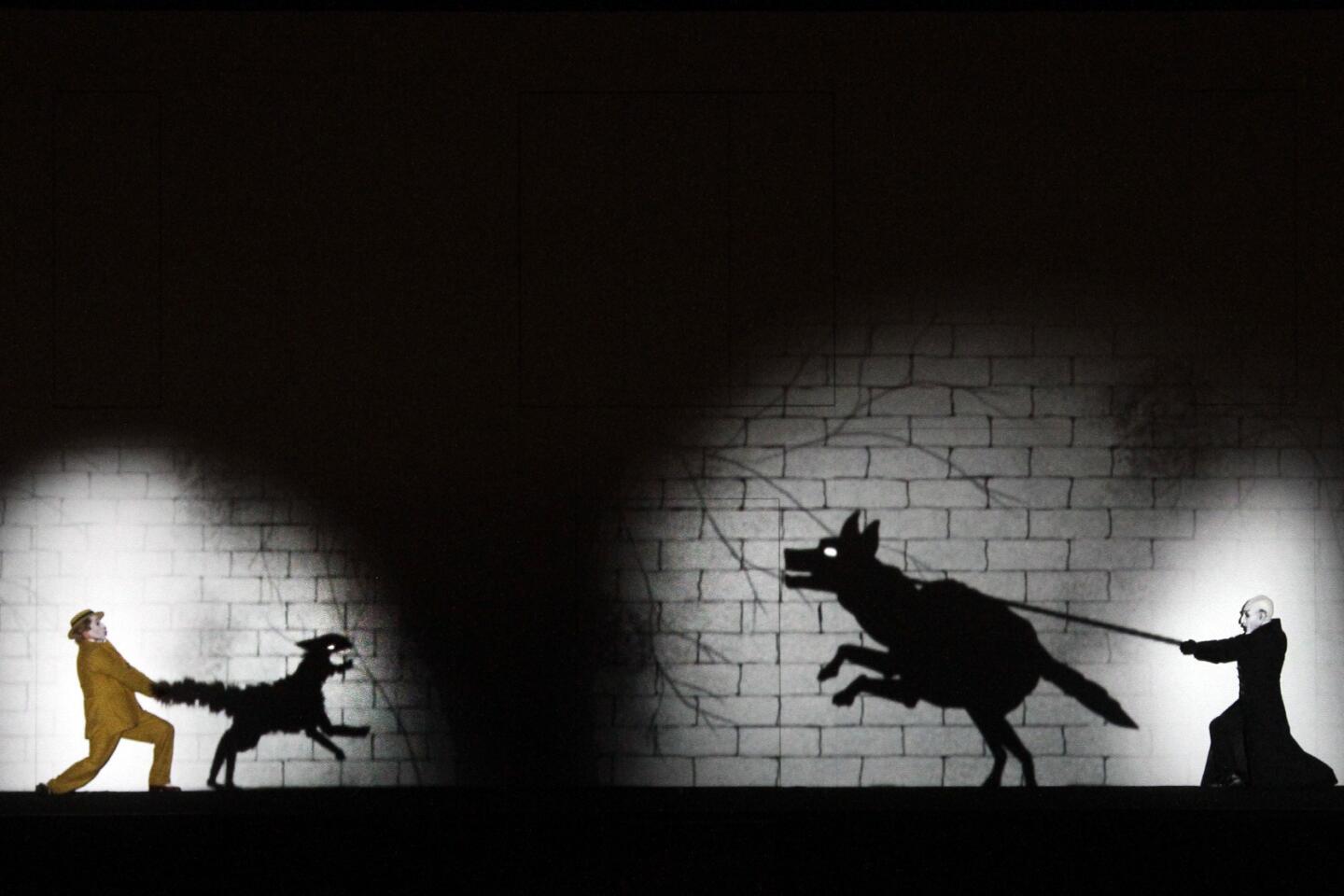

Much else is funny as well, as Mozart meant his opera to be, even if Kosky ultimately turns just about everything into a joke. Some characters become specific silent film personas, and that pretty much works. Papageno, the bird catcher, is Buster Keaton, though not as sad-faced. Pamina, whom Tamino pursues, is Louise Brooks in her Lulu haircut. Monostatos, the mean Moor, is Nosferatu.

Kosky replaces the opera’s sometimes-tedious spoken dialogue with silent movie intertitles. They are accompanied by excerpts from Mozart’s C-minor and F-minor keyboard fantasies on a period hammerklavier rudely yet delightfully amplified to resemble a barrel-house upright.

For all the fun, Kosky’s “Magic Flute” also has a subversive context. The production comes from the Komische Oper, the avant-garde and typically controversial Berlin company that Kosky has headed since last year. In addition, he collaborates with a young British theater company, 1927 (named for the year “The Jazz Singer” ushered in the talkies), that mixes theater, music and animation. All of this is clearly poking fun at the spiritual reverence with which Berliners hold “Flute.”

The first great recording of the opera was a glowing account by the Berlin Philharmonic under British conductor Thomas Beecham in 1937. Just last month, the Berlin Philharmonic released a new recording of the opera, on DVD. It is led by Simon Rattle, who is quoted on the jacket as saying, “Let’s not forget what a raging masterpiece” the opera is.

PHOTOS: LA Opera through the years

This is exactly what Kosky and his 1927 co-director, Suzanne Andrade, along with 1927 animator Paul Barritt, intend for us to forget in their fine entertainment. Kosky, in fact, is a slippery character. He says in the L.A. Opera program book that everyone knows “The Magic Flute” and that an 8-year-old can enjoy it. He told The Times the opposite: that he hated Mozart’s opera when he saw it as an 8-year-old and that his 1927 collaborators had never heard of it when he first approached them.

Not every production of “Flute,” of course, needs to explore the social and spiritual intentions that Kosky’s has little use for. Thus, the mysterious high priest Sarastro, in top hat, may be meant to merely represent Georges Méliès, the early French fantasist filmmaker whose 1902 “A Trip to the Moon” seems to have inspired some of Barritt’s imagery. Sarastro’s domain is full of fin-de-siècle machinery.

There are many visual surprises. I’m not going to spoil them other than to say that the pink elephants are pure pleasure and that the butterflies are a little too cute in a Hallmark card sort of way. For all that is gained, some things are lost in this extravagant animated conceit.

The music, although not secondary, can sometimes seem to take on an accompanimental role. The singers are so challenged with their exacting moves that they must often struggle to project the character of Mozart’s score. The cast, probably necessarily, relies on emerging singers game for such a challenge.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

Janai Brugger, who has sung secondary roles with L.A. Opera, is a rapturous Pamina ready for prime time. Lawrence Brownlee presents a bright Tamino; Rodion Pogossov, a sweet slapstick Papageno; Amanda Woodbury, a sexy Papagena. Not everyone in “Flute” is meant to be endearing, especially Monostatos, but Rodell Rosel makes him the kind of vampire you’d like to take home as a pet.

Less effective are Evan Boyer, a small-voiced Sarastro, and Erika Miklósa, a still Queen of the Night. Both seem straitjacketed in solitary poses they can’t quite seem to overcome.

James Conlon has had experience conducting “Flute” on film. He was responsible for a more intense performance used in 2006 as the soundtrack for Kenneth Branagh’s fine version of the opera. For Kosky, Conlon lights up and maintains a sprightly pace that feels natural despite the production’s demanding cinematic needs.

In the end, Kosky’s “Flute” may be more remarkable as a hybrid of film and theater than of cartoon and opera. But it is fun, if, perhaps, an uncharacteristically tame debut for a provocateur.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.