Study sends ‘wake-up call’ about black and Latino arts groups’ meager funding

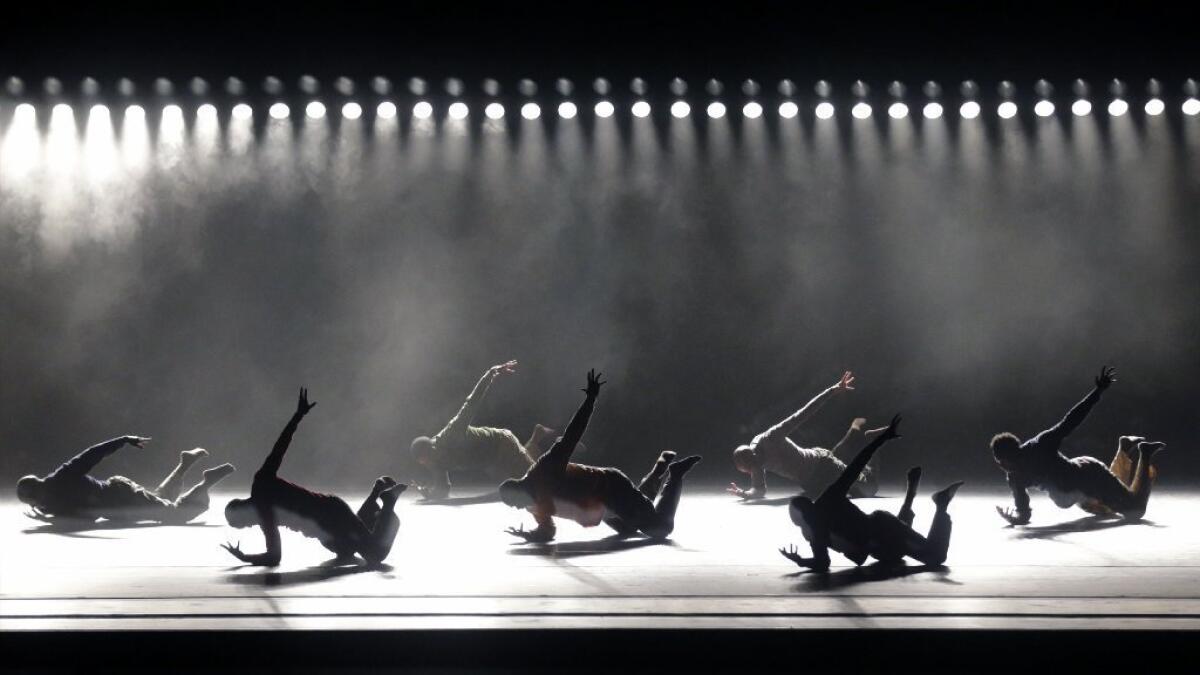

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, seen performing in April at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles, is the only minority-based arts group in the nation that’s able to consistently muster annual budgets greater than $5 million, says a new study intended as a “wake-up call” about the finances of most black and Latino arts groups.

Sending “a wake-up call” to arts donors, a new national study paints a bleak economic picture of African American and Latino nonprofit museums and performing arts companies and suggests that donors may have to let weaker organizations wither so that the strongest ones can grow.

Funders may need to support “a limited number of organizations,” says the report by the University of Maryland’s DeVos Institute of Arts Management, “with larger grants to a smaller cohort that can manage themselves effectively, make the best art, and have the biggest impact on their communities.”

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

The “Diversity in the Arts” report contains another potentially controversial finding: When large, mainstream arts organizations put on black- or Latino-themed performances or exhibitions, they siphon away artistic talent, donations and attendance from black and Latino companies.

“In 2015 a large number of arts organizations of color are struggling, in some cases desperately,” says the report, overseen by Michael Kaiser, the veteran arts administrator and former Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts president who heads the DeVos Institute.

Although many of these organizations produce important work, “the majority are plagued by chronic financial difficulties that place severe limits on what can be produced, how much can be produced, how many artists are trained, and how many people are served,” the report says.

To develop its financial profile, the DeVos Institute used tax returns for what it ranked as the 30 largest African American and 30 largest Latino nonprofit arts groups nationwide, by budget, in the fields of theater, dance and museums. The institute compared them with 20 of the biggest general companies in those fields.

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, a touring company that’s based in New York but has a national audience and donor base, is the only minority arts company that consistently mustered annual spending of more than $5 million during the 2009 to 2013 period the report examined. In fiscal 2013, the Ailey company spent $35.4 million, making it the 17th largest on the DeVos list of blue chip groups (though that list is not comprehensive, leaving out, for example, L.A.’s biggest-budgeted museum and its largest theater company, the Getty Museum and Center Theatre Group).

The median annual spending for the big arts groups on the DeVos list was $61.1 million in 2013, compared with a $3.8-million median budget for the 20 largest African American and Latino arts groups in the study. Median means half the organizations in a category are above that figure and half are below.

The report said that minority-focused arts organizations’ most debilitating weakness has been difficulty in attracting private, individual donors, a demographic whose charitable giving far exceeds the grantmaking of foundations, corporations and government.

Wealthy individuals typically make the big gifts that can transform an organization, but Kaiser said it’s also important to develop a large base of individual backers who loyally give smaller amounts.

A survey to which 29 of the 60 black and Latino arts groups in the study replied showed that the median percentage of donations coming from individuals was 5%. The norm is about 60% for big mainstream arts organizations.

“This is the most important single statistic in the study,” the report says.

Minority arts organizations also trailed when it came to box office receipts and other earned revenue. Earned money accounted for 40% of their revenue, compared with 59% for the big mainstream groups.

The aim of the report is to make these disparities clear and spur efforts to improve minority companies’ management and funding, Kaiser said in a recent interview.

“It’s a wake-up call,” he said. “I would like serious arts funders, regardless of their ethnicity, to be thinking about this issue.”

He acknowledged the Darwinian harshness of suggesting that some black or Latino companies might have to be left behind so their stronger peers might grow.

“It’s not politically easy or palatable, but it’s a potential solution that does need to be considered,” Kaiser said. “I am concerned that so many organizations are just holding on, with so little resources that they can’t create the size and quality of work that draws more donors and audiences. They get sicker and sicker. If there can’t be more funding, some funders will have to make choices.”

The report recommended that the minority-based arts groups and their prospective funders forget about campaigns to build new facilities, which can attract large donations. Instead, they should focus on boosting programs before considering improving their venues.

Racial diversification has been a prominent concern in the arts since the 1980s. Efforts toward multiculturalism and diversity led to at least a token minority presence in the performance and exhibition schedules of many organizations, with some companies recognized for going further than others.

But DeVos points to unintended consequences.

“It was totally well-intentioned, but I think it backfired a bit,” Kaiser said. “Big companies started to do African American and some Latino work, which is wonderful, but in some ways it was taking away resources from organizations of color.”

The report says that in their diversification efforts, “eurocentric organizations oftentimes select ‘low-hanging fruit’ -- the most popular pieces by artists of color that feature the most famous performers and directors of color,” leaving the small companies stuck in a cycle in which they can’t tap into star power or famous titles.

Kaiser said one solution might be for better-funded mainstream companies to share the wealth by co-producing star-powered productions of well-known titles with small companies of color in their communities. He cited the Kennedy Center’s work with the Atlanta-based True Colors Theatre Company on a monthlong production of all 10 plays of August Wilson’s “cycle” of dramas about the African American experience in the 20th century.

But Janet Brown, president of Grantmakers in the Arts, a national consortium of about 300 charitable foundations and government grantmaking agencies, said questions have arisen over whether such partnerships yield equitable benefits for the smaller company.

Brown said that the DeVos Institute’s report is not the first time these issues and suggestions have been raised, but that it’s a welcome addition to the discussion.

Ideas such as philanthropic triage and the unintended drawbacks of mainstream groups’ diversity efforts were part of a discussion at a June 2 forum in Atlanta that Grantmakers in the Arts sponsored, Brown said. But she cited the statistical documentation in the DeVos report as a helpful new dimension in the conversation about addressing inequities, adding that the new report is more likely to find its way onto the radar of individual donors.

Grantmakers in the Arts issued its own “Racial Equity in Arts Philanthropy Statement of Purpose” in March, including an acknowledgment that the existing system isn’t working. “Solutions of the past, which have focused on diversity rather than structural inequalities, have not resulted in nationwide successful outcomes” for minority artists and audiences, it said.

Charts in the DeVos Institute’s report show that only one black organization, the Ailey dance company, and one Latino group, the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach, had endowments of $10 million or more at the end of their 2013 fiscal year -- $55 million for Ailey and $23.8 million for MOLAA. The Long Beach museum’s endowment was a bequest from its founder, art collector and heallthcare businessman Robert Gumbiner, after his death in 2009.

Most of the minority arts groups in the study had no endowment; others with endowments of more than $1 million were Repertorio Español in New York, the Studio Museum in Harlem, Reginald F. Lewis Museum in Baltimore and the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture in Charlotte, N.C. Their endowments ranged from $4.2 million to $7.6 million -- amounts that can be expected to yield $210,000 to $380,000 a year for programs and operations, based on a typical 5% withdrawal.

The California African American Museum in L.A.’s Exposition Park was not included in the report because it’s a state-chartered organization rather than an independent nonprofit group, a DeVos spokesman said.

Follow https://twitter.com/boehmm of the LA Times for arts news and features

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.