Carlos Almaraz’s time is coming, nearly 30 years after death

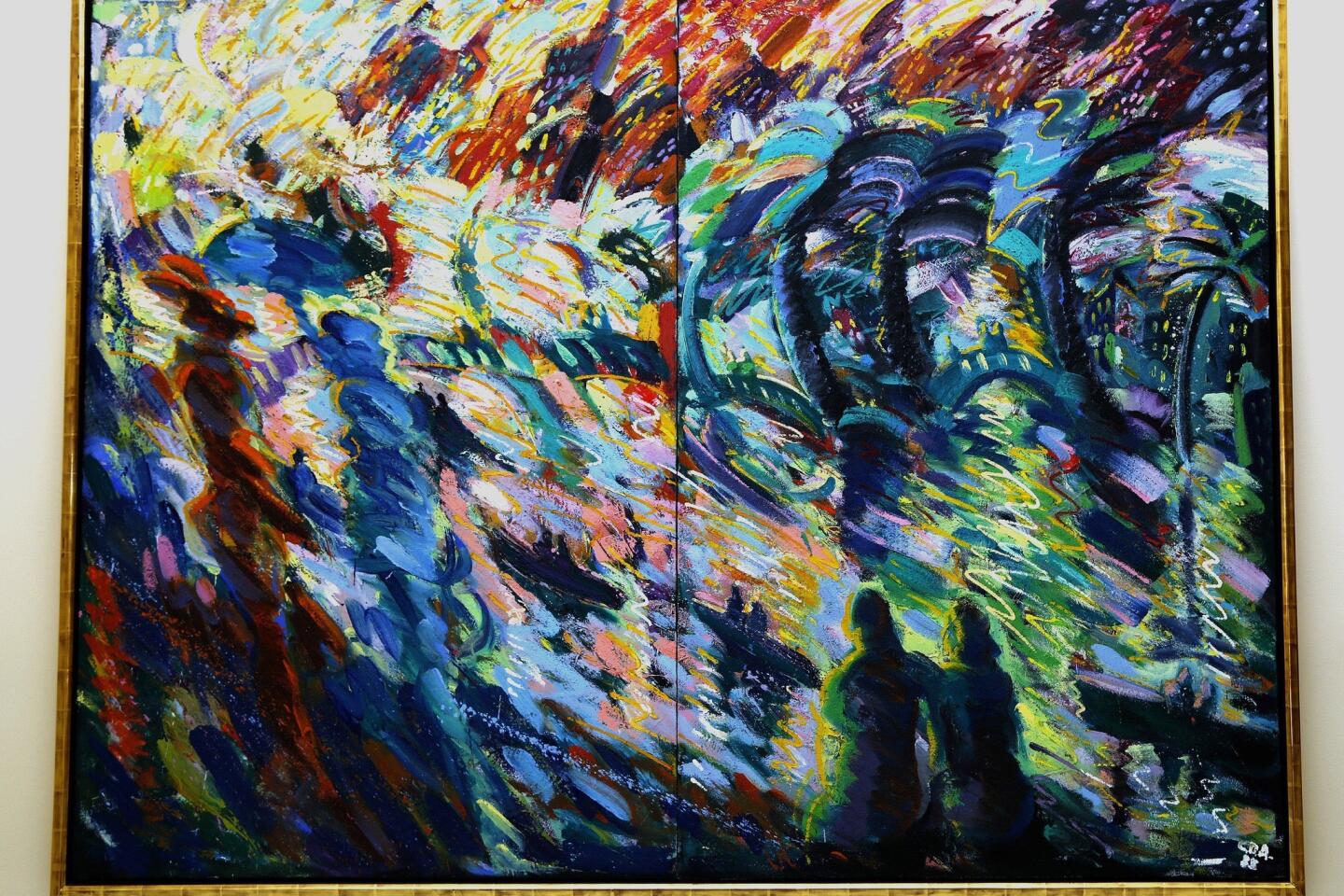

Beautiful and terrifying, the painting hangs in the foyer of Cheech Marin’s oceanside home. It depicts a car crash on the upper deck of an L.A. freeway, an appallingly seductive vision of maimed metal erupting into fauvist-tinted fireballs.

“That’s the fascination, that fear-attraction simultaneously,” says Marin, best known as the more antichalf of the comic duo Cheech and Chong.

Three years from now, “Sunset Crash” will be among the big draws of the most comprehensive exhibition devoted to Carlos Almaraz, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Titled “Playing With Fire,” it will be part of “Pacific Standard Time: L.A./L.A.,” a Getty-funded, multi-venue initiative that will explore artistic connections between Los Angeles and Latin America.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Curated by Howard Fox, the Almaraz show will sidle up to an artist who, a quarter-century after his death at 48 from AIDS-related complications, remains a charismatic and enigmatic lightning rod. “Carlos is really unique,” says Fox, a former LACMA contemporary art curator who retired in 2008 but, like a restless gumshoe in a film noir, has been lured back into action by the project. “He had his own idiom, and it was both fabulous and dark, tortured and joyous.”

That leaves one pressing question for Fox and friends to solve: What happened to the majority of Almaraz’s works? Although the locations of some are known, the whereabouts of many others is a mystery. Marin, with about 20 pieces including paintings and water colors, is likely Almaraz’s single biggest collector. Gerald Buck, a Newport Beach developer and collector who died last summer, also had significant Almaraz holdings, as does the L.A. office of Deloitte Corp., which like other major businesses collects art both as investment and adornment.

“Very few artworks were purchased by Chicano collectors,” says artist Elsa Flores, Almaraz’s widow. “Now there are more. But back then most of his supporters were people from the Westside, attorneys, doctors.”

Fox says that Almaraz was “very punctilious” about photographing 4-inch-by-5-inch transparencies of his artworks, about 250 altogether. But only a handful of these were identified by title, and the sales histories of many are murky. “Carlos’ own record-keeping was anemic at best,” Fox says.

PHOTOS: Best art moments of 2013 | Christopher Knight

Fox adds that the uncertainty over what happened to many of the works reflects the relative youthfulness of Chicano studies as an academic and curatorial field. “It’s not surprising that the history is not fully accounted for.”

In coming months, Fox will continue playing private eye, tracking down tips and seeking out collectors by phone, email and in person. Assisting him will be Flores and gallery owners Jan Turner and Craig Krull, who collectively have represented Almaraz for many years. (Limited auction records show his paintings have recently sold in the $10,000-$20,000 range, and occasionally higher.)

Flores says that last fall, when she sent out announcements about her annual studio art sale, she added a personal note asking colleagues and collectors for any tips they might have about her late husband’s work. Those have yielded good leads. But she and Fox are seeking major canvases like “Europa and the Jaguar,” which blends classical Greek and pre-Columbian mythology and motifs.

“Because there’s so few works on the market, it’s tricky,” says Flores, who possesses a variety of Almaraz’s work, including paintings, pastels, line drawings and prints. “And people don’t know that I exist. I don’t advertise. Collectors who find me, they either stumble upon me or they’ve asked someone how to reach me.”

PHOTOS: The most fascinating arts stories of 2013

Fox says that as recently as 1984 he included “Europa and the Jaguar” in exhibitions at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., and subsequently in a LACMA show organized by the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, “Hispanic Art in the United States: Thirty Contemporary Painters and Sculptors.” But the San Antonio gallery that lent him the painting has sinced closed, Fox says.

“I’m going to have to call some people in San Antonio and just cold-call and hope that somebody remembers where it was last time they saw it. But for the moment it’s missing in action.”

To support Fox’s efforts, LACMA has set up a phone hotline [(323) 857-6231] and a dedicated email address ([email protected]) so that anyone with information or questions can make contact.

It’s an appropriately irregular act on behalf of an artist who defies easy categorization. LACMA hopes the Almaraz show will bring more attention to an artist who, as former Times art critic William Wilson put it, “has come to symbolize the dilemma of minority artists torn between the urge of individual aesthetic freedom and a sense of obligation to their community.”

PHOTOS: Faces to watch 2014 | Art

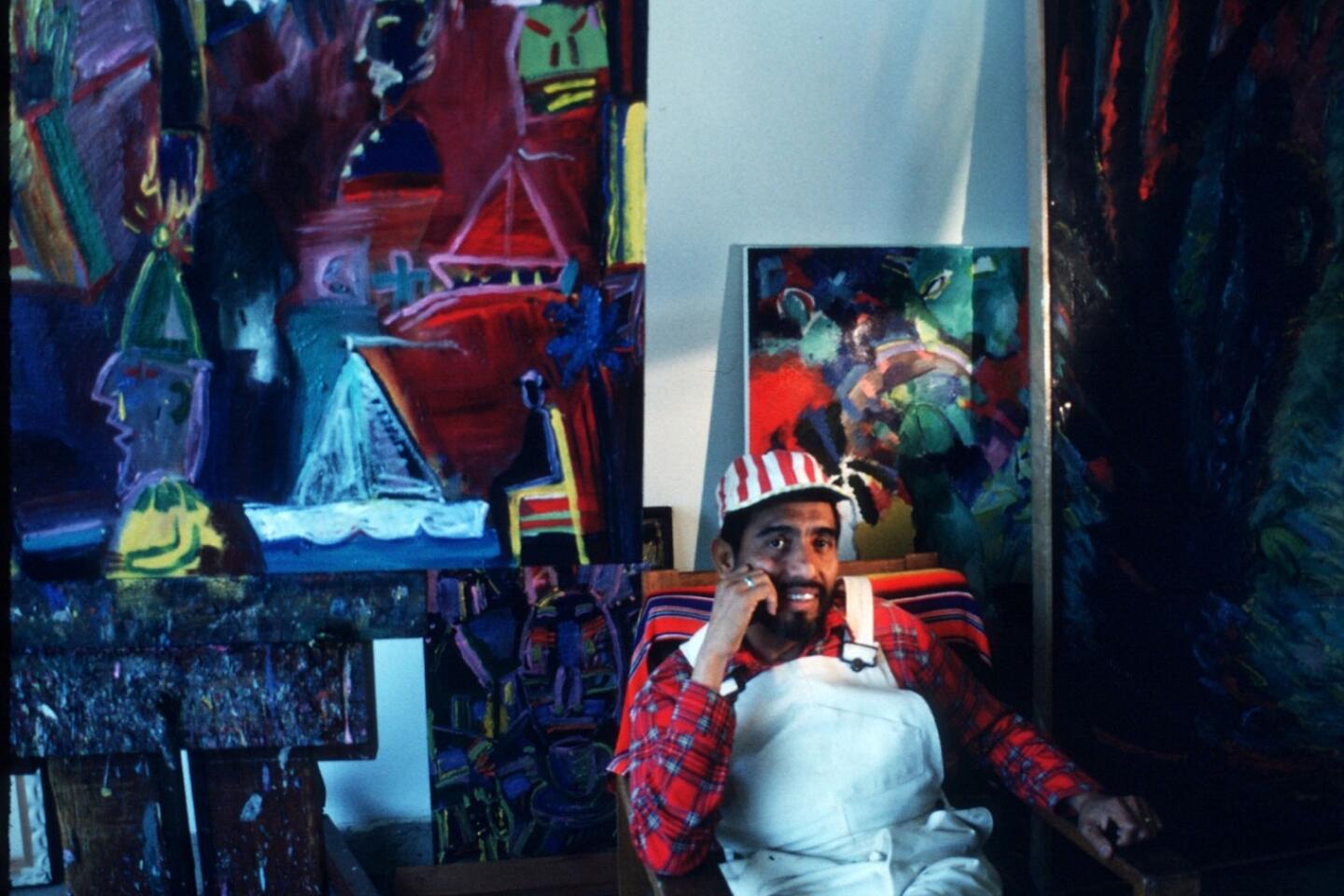

Mexico, Chicago, SoCal

Born in Mexico in 1941, Almaraz was raised in Chicago and later moved with his family to Southern California, settling in Chatsworth, Watts-Compton and East L.A. “He was never an East L.A. Chicano,” says Flores, who’s making a documentary feature about her late husband. “In fact, he was an oddball.”

Almaraz’s formal art training began in 1959, when he enrolled at Cal State L.A. He later received a full scholarship at what then was called Otis Art Institute of Los Angeles County. He also studied at UCLA.

In 1965, Almaraz relocated to New York, where he became close friends with another L.A. painter, Frank Romero. His omnivorous appetite for different styles and periods of art permanently marked his own production. His serigraphs of the Manhattan skyline quiver with anxious energy reminiscent of Italian Futurism (or perhaps they’re swaying to salsa beats?). His romantically backlighted Echo Park scenes evoke Monet’s Giverny waterscapes. And his skeletal faces and masks are the phantom offspring of both Aztec spirits and James Ensor’s proto-modernist caricatures.

“He always said, ‘I’m an American artist who happens to be Chicano,’” Flores says.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

Personal conflict

During his New York residency, Flores says, her future husband began to explore his bisexuality. These forays left the Catholic-raised artist deeply conflicted, alternately euphoric and guilt-ridden, drinking heavily. That psychological duality at times found expression in his aggressively sensual color palette, visual double meanings and imagery shaded with erotic innuendo.

“That was not a good period for him,” Fox says of Almaraz’s New York sojourn. “Minimalism was just gearing up. Nobody wanted to see Hispanic representational paintings.”

In 1965 he moved back to L.A. and promptly “became a born-again Chicano,” a cultural warrior in the Chicano Power movement of the 1960s and ‘70s, Flores says. As a member of the Los Four quartet, along with Romero, Roberto “Beto” de la Rocha and Gilbert “Magu” Lujan, he battled the political and art establishment with spray cans and slogans. Declaring that “I love people more than art,” Almaraz for a while worked as a Boyle Heights social worker.

But after marrying Flores and becoming a father, he withdrew into family life and more introspective artistic preoccupations, a move that alienated some of his Chicano friends and colleagues, some of whom thought he was turning his back on el movimiento.

ART: Can you guess the high price?

“He wanted to be a painter, wherever that led him,” Marin says.

Marin first pitched the idea of an Almaraz retrospective several years ago to LACMA director Michael Govan. When Govan agreed, Marin then recruited Fox to curate the exhibition. Subsequently, LACMA decided to make the exhibition part of its contribution to “PST: L.A./L.A.”

“PST 2,” as it has been dubbed, is a follow-up to the Getty’s 2011 “Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980,” which recruited dozens of regional arts institutions to tell the story of post-World War II Southern California art.

Fox believes “PST 2” will intensify the attention paid by “the Eurocentric and East Coast art establishment” to “the whole connection between North and South America” in art. Few artists may be more representative of those complex connections than the man whose art wrested beauty from violent destruction and yielded an Oz-like vision of a changing L.A.

“Carlos Almaraz was the John Coltrane of the movement,” Marin says. “He was so far out there that we’re just still catching up with him.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.