Review: Gustavo Dudamel, L.A. Philharmonic focus on Apollo

God of light and music, Apollo stood for clarity, harmony and reason. He was healer and protector to ancient Greeks and beyond. It was to the sun god that three major 20th century composers turned in the troubled years between 1927 and 1939 — a period of international economic collapse, the rise of dictators and the buildup to world war.

Gustavo Dudamel led the Los Angeles Philharmonic in a program Friday (and repeated Saturday and Sunday) centered on Apollo. The main attraction was Igor Stravinsky’s ballet, “Apollo,” presented in collaboration with American Ballet Theatre and featuring dancer Roberto Bolle. That was sandwiched between Benjamin Britten’s “Young Apollo” and Dmitri Shostakovich’s apollonian Fifth Symphony.

Each of the three works represented a departure from earlier reckless experimentalism to cautious classicism. And each piece revealed, in different ways, an anxious composer newly excited by musical tradition.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

The earliest of these works, Stravinsky’s serenely tonal ballet blanc, was a striking reversal from the uninhibited adventurousness of “Rite of Spring,” written 14 years earlier. In nostalgic tribute to the Russian ballet of his youth, Stravinsky chose the subject of Apollo and three of the god’s muses — those of dance, mime and poetry — as part of the composer’s neoclassical comfort in artistic purity over savagery.

The orchestra, a small contingent of strings, is monochromatic. The harmonies allow for sublime consonance. The dance numbers are easily graspable. Melody is applied with joy. Yet the old-fashioned score is peppered with just enough metric surprise to keep the context fresh, like mixing modern furniture with antiques.

For Dudamel, Stravinsky’s “Apollo” became his latest effort to bring dance to Disney. ABT set up on a platform behind the musicians. The choreography was the famous ballet that George Balanchine created for the 1928 Paris premiere of the score, beginning one of the greatest long-term collaborations between composer and choreographer.

Here the young choreographer finds strikingly clever balletic movement with touches of modern design to match Stravinsky’s. But he’s too clever. By being both showier and more traditional than Stravinsky, the dance becomes more dated than the music.

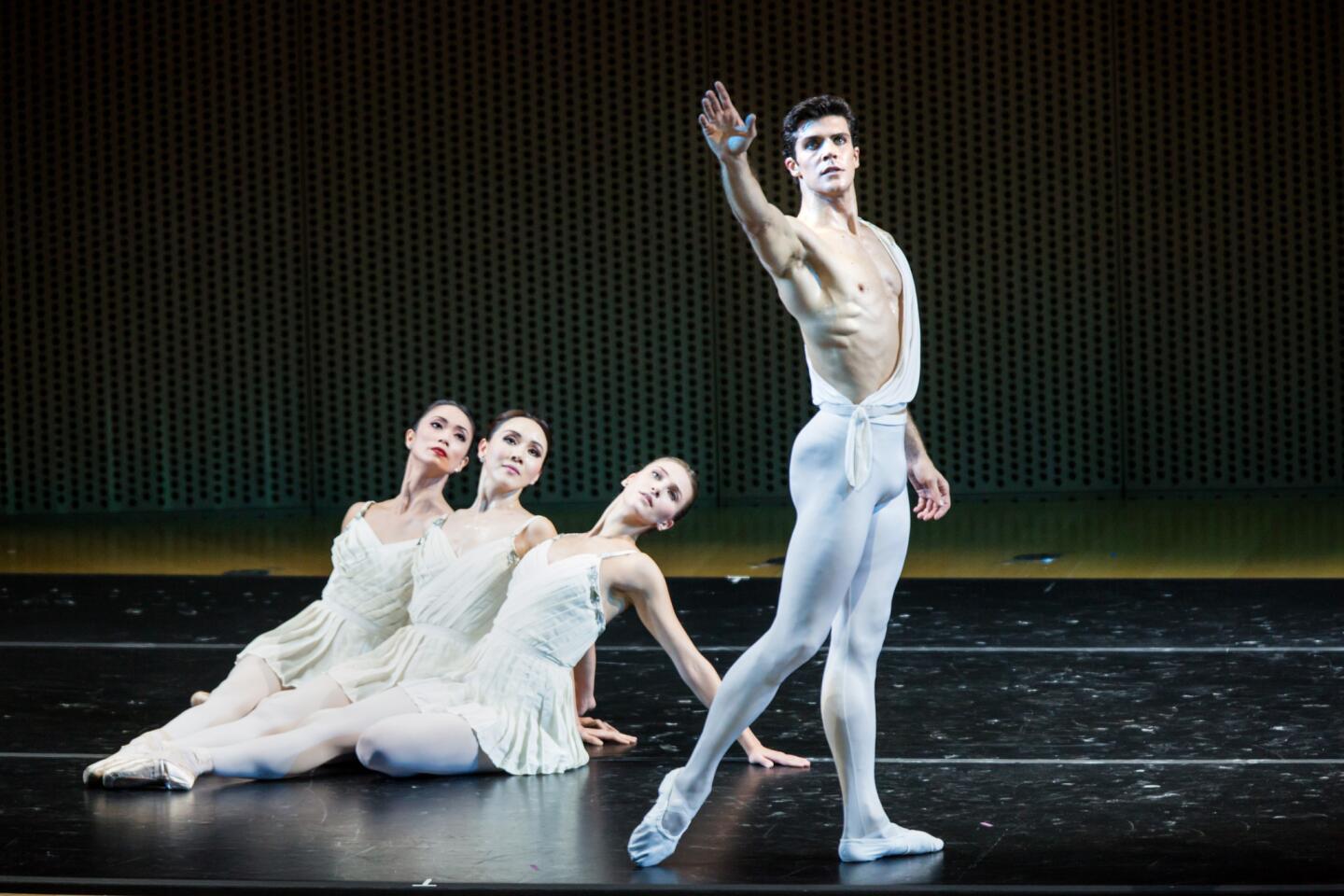

Antique grace, all light and delicate, can be a saving grace. Bolle, however, with his chiseled muscles, is very much a modern Apollo. He was superbly strong, but when he rotated his arms with the impressive mechanical strength of a windmill, the effect was like playing ancient music on an inappropriately modern instrument.

He was joined by three capable muses — Hee Seo, Devon Teuscher and Stella Abrera — and his pas de deux with Seo’s Terpsichore was stunning. But given the acoustics of Disney Hall, the dancers’ feet overpowered delicately muted strings.

Britten’s “Young Apollo” is the work of a young composer, just arrived from England in North America, escaping war. This is Apollo, the sun god, dazzling.

The seven-minute miniature for piano, string quartet and strings may be Britten’s flashiest score, and he soon dismissed it. The piano part, brilliantly played by Joanne Pearce Martin, is a riot of scales. The strings strut their melodic stuff without embarrassment. The harmonies remain almost static. The world then was less frivolous, and so would be Britten soon. But a sun god’s undiminished radiance may have helped him find his way.

Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony has little overt relation to these other works, even if the composer was Russian, like Stravinsky, and came to be close friends with Britten. This Fifth Symphony is a desperate attempt at achieving Apollo’s luster for sheer self-preservation.

After his controversial modernist scores had gotten him in trouble with Stalin, Shostakovich famously produced this triumphant symphony as “a reply to just criticism.” The work follows conventional symphonic structure more rigorously than the symphonies that preceded it, especially the unhinged Fourth.

We argue now about what Shostakovich really meant with what has become his most popular work, whether it was tribute to or secret parody of a tyrant.

But Dudamel, in a revelatory performance, treated it as neither. Rather, it was the tragedy of triumphalism. Had the premiere in Leningrad (as St. Petersburg was then known) in 1937 been like this, Shostakovich would have likely wound up in Siberia.

Dudamel went for dark textures and illuminating details, moving inexorably forward as if this were a Greek tragedy. There was no grotesquerie. The Finale lacked its usual bombast or enthusiasm. But everywhere there was a sense of exploration, of getting inside the notes.

And the L.A. Phil was Apollo’s orchestra, however grim, every minute dazzling in its grandeur.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.