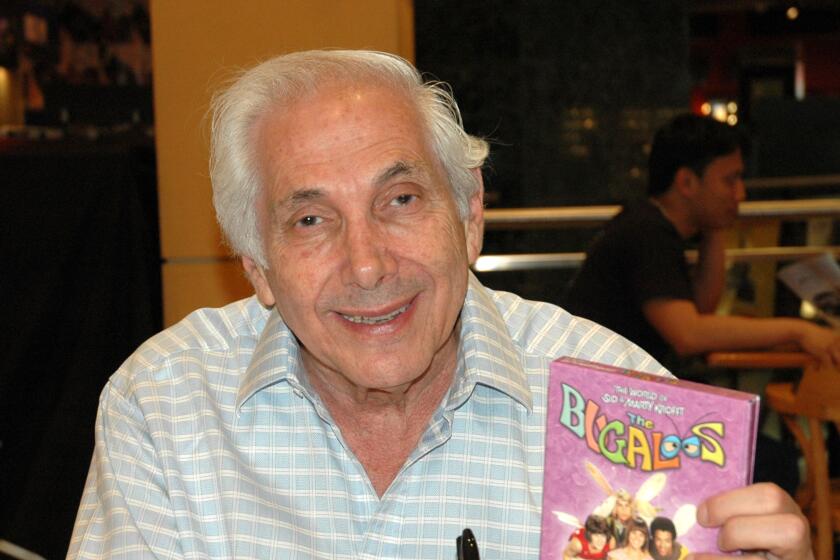

Appreciation: Marty Krofft was integral to a creative partnership: ‘I get a dream and Marty gets it done’

Marty Krofft, the younger of the two brothers who formed the creative team of Sid and Marty Krofft, died Saturday at the age of 86 — a day of the week with whose morning his work will always be synonymous.

Although the Kroffts’ great decade was the 1970s, Marty kept working his whole life, going to the office, floating new projects and bringing some to fruition because, he liked to say, retirement would kill him. “We got some plans that are great that we can’t share today,” he said a couple of years back during one of his “Mondays With Marty Krofft” YouTube videos (a sort of sequel to his brother’s Instagram Live show, “Sundays With Sid”). “I’m 120 years old and I’m still getting shows on the air — so don’t mess with me.”

Fortunately, there has always been an appetite, if not always for new Krofft content, then for the old content, re-released or reimagined, and for the Kroffts themselves, who left a permanent mark on a generation of young Americans with shows such as “H.R. Pufnstuf,” “Lidsville” and “The Bugaloos”: high-concept puppets-and-people shows set in fanciful lands among remarkable creatures — a dragon mayor, anthropomorphic hats, a British pop band whose members were insects, sort of.

Marty Krofft, the TV creator behind the children’s shows “H.R. Pufnstuf” and “Land of the Lost,” has died. He was 86.

One or both of the brothers were regular presences at the San Diego Comic-Con and other such conventions around the country; last year saw the first, and perhaps not the last, dedicated Krofft Kon. Their last big show, “Mutt & Stuff” for Nick Jr., featuring a human host, a pack of real dogs and puppets of varying sizes, was their first geared to a preschool audience, and also their biggest, if reckoned by the number of episodes. The young adults of the 2030s may recall it fondly.

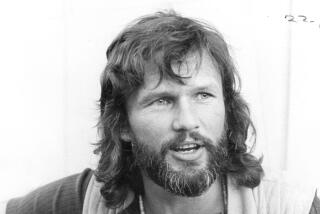

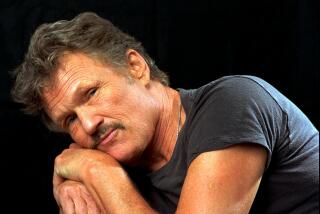

Watching the brothers interviewed side by side, one would say that Marty was the business in this partnership, and Sid, a professional puppeteer from age 10, the show. It’s an impression the brothers have often confirmed. (“I get a dream and Marty gets it done,” said Sid.) Sid, soft-spoken, radiating a kind of beatific innocence, is the older by almost eight years but seems that many years the younger; Marty, fidgeting while Sid tells some long story, will jump in to get to the point. But each acknowledges the other’s creative contribution.

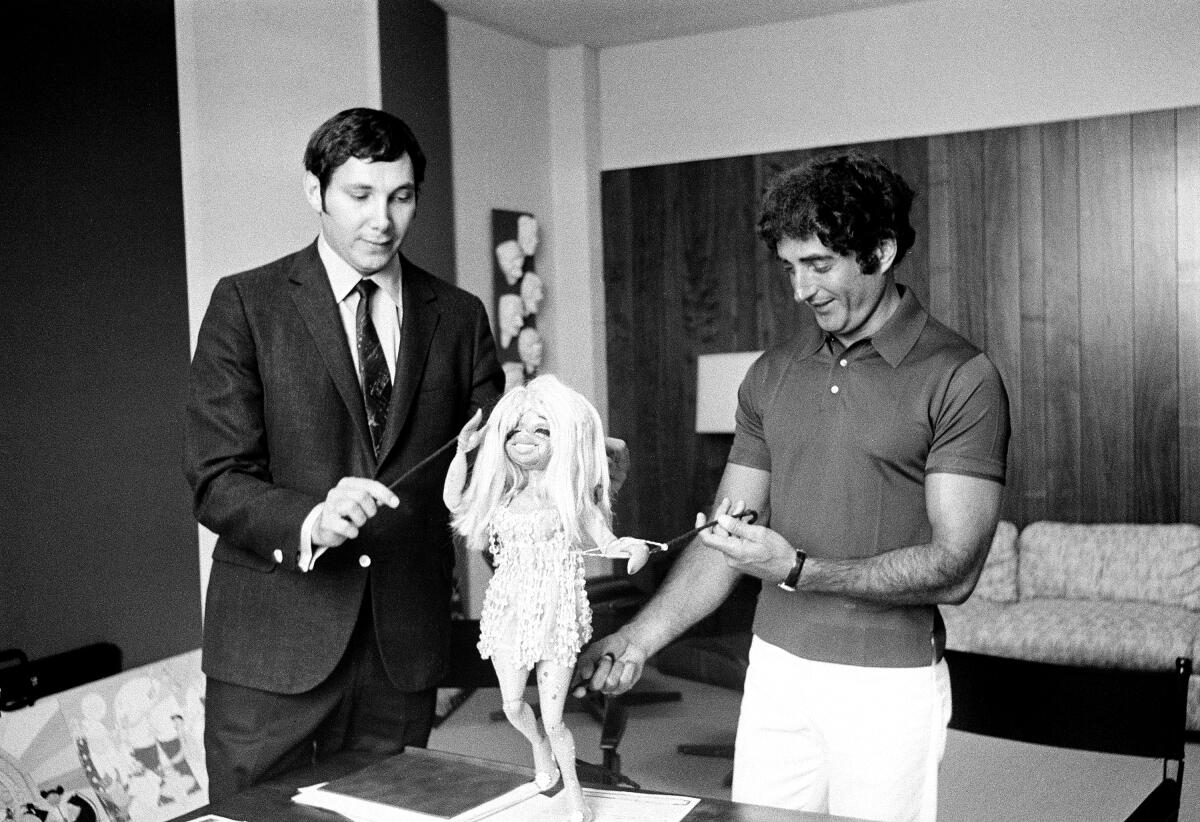

Marty was still in rompers when Sid began performing; the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus billed him as “the world’s youngest puppeteer.” He toured the world, while Marty re-created his act back home, and opened for the likes of Judy Garland and Liberace. By the 1950s the brothers were working together; in 1957, they created “Les Poupées de Paris,” a “topless” puppet revue, “à la the Folies Bergère,” which opened at the Gilded Rafters, a new, Las Vegas-style restaurant and theater in the San Fernando Valley and played later at Hollywood’s P.J.’s. (Krofft generation kids may know it as the Starwood.) The show traveled to various world’s fairs, with entry restricted to adults; evangelist Billy Graham saw it in Seattle, more or less by accident, and ensured its success by denouncing it. Another big show, “Kaleidoscope,” cooked up for the San Antonio’s HemisFair ‘68, starred a dragon character named Luther that would eventually be reupholstered as H.R. Pufnstuf, and led to the creation of the brothers’ Show Business Factory, which supplied props and costumes for their shows and other clients.

Premiering in September 1969, between the Woodstock and Altamont music festivals, “H.R. Pufnstuf” was the Kroffts’ first created series; they had earlier built costumes for Hanna-Barbera’s “The Banana Splits.” If you have been so unlucky as to have never made its acquaintance, it tells the story of Jimmy (played by Jack Wild, the Artful Dodger in the movie musical “Oliver”) and his best friend, a solid gold, jewel-encrusted flute named Freddy. (“People love flutes that talk,” Marty said earlier this year on an edition of “Mondays,” “and flutes that talk are home runs.”) They’re shanghaied by Witchiepoo (Billie Hayes), basically evil but also adorable, to Living Island — the witch wants Freddy — where trees walk and objects talk and the mayor is the title character, a friendly dragon. (In its wholesale anthropomorphism and wealth of puppets, it anticipates “Pee-wee’s Playhouse,” and Paul Reubens and Sid Krofft were indeed good friends.)

(Less genially, McDonald’s ripped them off for its McDonaldland campaign — compare Mayor McCheese to H.R. Pufnstuf, just to start. The brothers sued for copyright infringement, and in a landmark case — Sid & Marty Krofft Television Productions Inc. vs. McDonald’s Corp., 1977 — won.)

Sid Krofft may have been feuding with his brother, but he’s always realized Marty Krofft’s importance in their success.

The Kroffts would also create and produce prime-time variety shows featuring Donny and Marie Osmond, the Japanese singing duo Pink Lady and the Brady Bunch — that is, the actors who played the Brady Bunch playing their characters in the context of a variety show — that were in their way as strange as the puppet and kids’ shows with which they’re most associated. (Every episode of “Donny & Marie” began on ice; “The Brady Bunch Variety Hour” featured a swimming pool for water ballet.) Later, the “D.C. Follies,” a late-’80s syndicated series along the lines of Britain’s “Spitting Image,” featured Fred Willard as the bartender in a Washington watering hole frequented by puppet versions of real-life political and show business figures. A clip from the 1984 “Richard Pryor’s Place,” featuring Pryor (on saxophone) and Willie Nelson duetting on “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” has been making the social media rounds lately, as a thing no one can quite believe.

The 1970s are often regarded as the poor stepchild of the ‘60s, culturally speaking, that exalted decade of transformation, when the world went in short order from straight to swinging to psychedelic. But in the ‘70s the visual byproducts of psychedelia were fully integrated into high fashion and mainstream culture — the bright colors, the squiggly shapes, the dreamlike scenarios — in a new and more fantastic way, a little garish, a little gaudy, even a little unattractive, in a winning way. Then came the glitter of glam-rock, or the glamour of glitter-rock — Glitter Rock was a villain in the superhero sendup “Electra Woman and Dyna Girl”— followed by the bright lights of disco and the art-damaged aesthetic of new wave. By the decade’s end, you had the Dickies punk-rocking the “Banana Splits” theme.

Central to the story the Kroffts continued to tell is that they were a relatively small, independent company among Hollywood combines, and so were often scrabbling. Low-budget production values — the painted flats, the very basic green screen effects — might have been all they could afford, but it gave the Krofft shows their particular character. They would produce slicker versions of “Sigmund and the Sea Monsters,” briefly revived in 2016 for Prime Video; a web-based “Electra Woman and Dyna Girl” the same year; and a Will Ferrell-starred “Land of the Lost” movie in 2009. They have their points, but none improves on the homely originals. The child of today, spoiled for choice in targeted programming, might sniff at the old shows, but a CGI “Pufnstuf,” which happily no one has proposed, would be all but pointless, and potentially depressing.

Kids’ shows, though often dull knockoffs of other dull knockoffs, have been at their best a refuge for creative minds whose inspirations adult programs can’t accommodate; they appeal, accordingly, to adults as well as children. There is no demographic for weirdness, or wildness. While their content might be informed by psychological or educational programs, only real inspiration can account for the peculiar worlds of “The Teletubbies” or “Yo Gabba Gabba!” As goofy as they may be on paper, or even on the screen, with their cartoon sound effects and boulevard-broad acting and bubble-gum pop songs, the work of Sid and Marty Krofft is the product of a genuine, unabashed vision. More than nostalgia, it’s the art that makes children of all ages into lifelong fans.

Last year, Marty guested as himself in an episode of Pamela Adlon’s “Better Things,” “Rip Taylor’s Cell Phone,” in which Adlon’s character spots Marty, in a “Land of the Lost” windbreaker, at the supermarket.

“Are you Sid or Marty?” she asks tentatively, trembling a little.

“I’m Marty — the good-looking one,” says Marty, adding, “Let me give you some advice that my dad gave me. Don’t ever, ever give up. Because if you give up on Tuesday, there is no Wednesday, and Wednesday could have been the day.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.