John Carpenter returns to the director’s chair with true terror anthology ‘Suburban Screams’

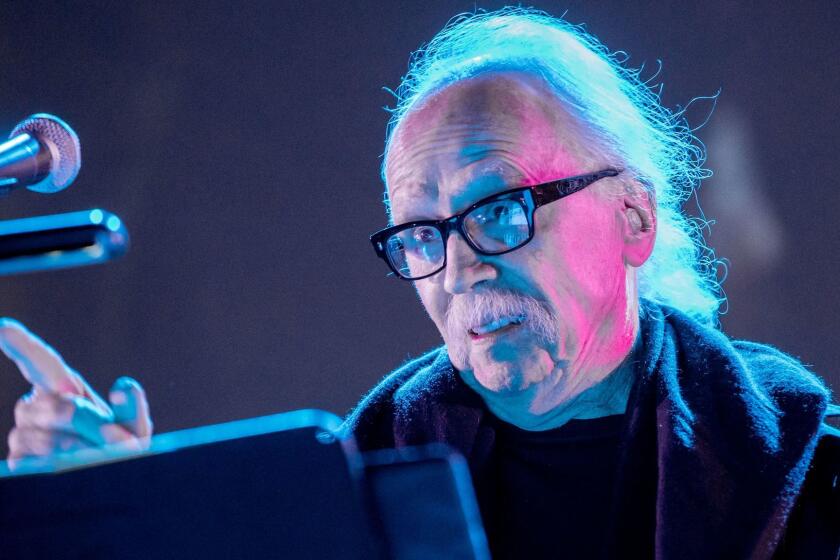

John Carpenter has a gift for conjuring frights where you least expect them — say like the terror of a masked maniac slicing up teens in suburbia to a hypnotic, dread-inducing synth score — and at 75, he still wields a wickedly droll sense of humor.

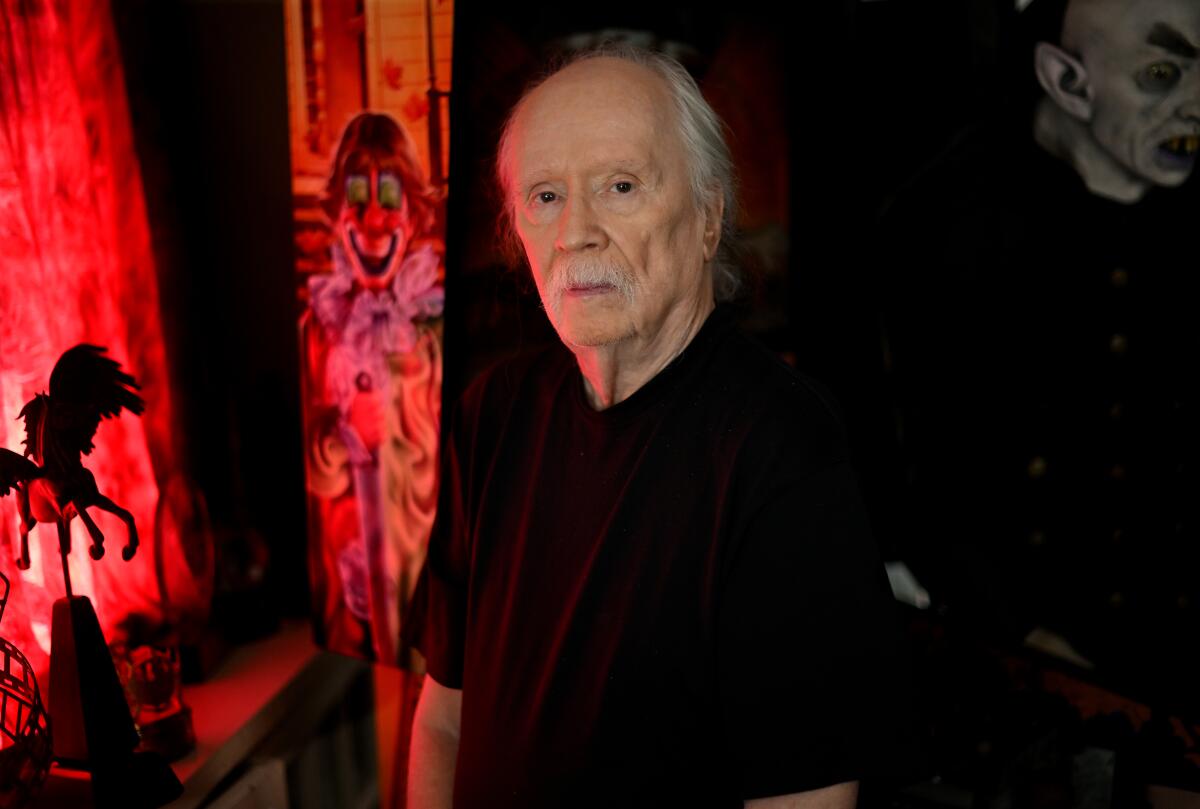

As we turn the corner into his office, the cheekily self-proclaimed “horror master” cackles at the sight that greets all who dare to enter: a life-size cardboard cut-out of “Believe”-era Justin Bieber.

“We have a friend who comes and stays with us,” the director explains of the guesthouse decor lurking beside his desk, a smile dancing across his face. “We stick it in there to scare him.”

It’s fitting that Carpenter keeps his headquarters hidden in plain sight. Just beyond a picturesque white picket fence in a sleepy Los Angeles neighborhood that’s nearly as serene as the South Pasadena locales where Michael Myers hunted Laurie Strode in 1978’s seminal “Halloween,” mementos from his career-defining films, from 1986’s “Big Trouble in Little China” to 1998’s “Vampires,” fill the walls.

But on a recent afternoon it’s the multihyphenate’s newer works — stacks of the graphic novels he and producer-wife Sandy King Carpenter publish through their Storm King Comics, and the albums he records with son Cody Carpenter and Daniel Davies — taking up every inch of free space in his home as he prepared for a trip to New York Comic-Con. (Out this week: his latest album, “Anthology II (Movie Themes 1976-1988),” featuring new recordings of his own iconic movie themes.)

Most of the features Carpenter directed since 1974’s “Dark Star” are now celebrated genre classics. And while he has returned as a composer and executive producer on the recent “Halloween” reboots, he isn’t one to rewatch his own films. (“They’re done, that’s the most exciting thing — I finished them.”) And despite the career highs and the fervent fandoms around his most influential works, no one remembers the heartbreak of the critical and commercial disappointments and the burnout that came as acutely as the artist himself.

When John Carpenter was a boy, he found some music paper and started scribbling away “like a crazy person,” he said.

Little wonder then that Carpenter often seems more eager to dive into topics of music, video games or basketball that fascinate him these days than wax poetic about his own films. “I love women’s basketball, the WNBA,” he says. “I don’t know who I’m pulling for this finals, whether it’s New York or the [Las Vegas] Aces.” Current faves? “A’ja Wilson is just an unbelievable player. She’s on the Aces. And Kelsey Plum.”

Yet 13 years after his last feature, “The Ward,” and over a decade and a half since his episodes of “Masters of Horror,” it was a new take on scary storytelling, in a new era of streaming, that enticed him back into the director’s chair.

In Peacock’s unscripted horror anthology “John Carpenter’s Suburban Screams,” which he executive produced, composed the score for and directed one of six episodes, Carpenter taps into his slasher roots to bring to life one woman’s true account of a mysterious phone stalker. (As for lending his name to the series’ title, Carpenter quips, “Now that’s an act of commerce.”)

Ahead of the show’s debut on Friday, the master of horror reflected on his return to directing and the uncensored moment he worked into “Suburban Screams,” the possibilities of an AI-generated future and why music, not movies, is the “purest form of art there is.”

You just attended an entire convention dedicated to your film “Halloween,” which celebrates its 45th anniversary this year. Did that hit you in some profound way?

It should, but it doesn’t. It’s work. I should be more appreciative, shouldn’t I?

Well, your relationship with your work and your art is yours to define.

I’ve had the greatest life because all I wanted to do when I was a kid is be a movie director. And I got to be, and it was unbelievable. I prepared for it. I went to school for it. I’m lucky. A lot of people aren’t so lucky. So I have nothing to complain about.

Your films have incredibly devoted followings. I know people who have “Halloween” tattoos inked on their bodies. What do you make of that?

I know this! It’s very weird. I remember thinking. What? Why is that? What’s going on here? Look, I’m very flattered. The film that I feel closer to my heart is “The Thing,” which was trashed big time when it came out. Now it’s a little more liked. But, boy, woo, when it came out. My God. I lost a job because of it. I got fired. I would have directed “Firestarter.” That was tough.

I’ve had the greatest life because all I wanted to do when I was a kid is be a movie director. And I got to be, and it was unbelievable.

— John Carpenter

Last year you came full circle in a sense by composing the score for the “Firestarter” reboot. You did the same for David Gordon Green’s recent “Halloween” movies. Have you kept up with his new remake of William Friedkin’s “The Exorcist?”

I like what David did when he made the three “Halloweens.” I loved No. 2 [“Halloween Kills”]. Thought that was fabulous. I heard “The Exorcist” really didn’t cut it. That could be a kickass movie. I don’t understand how you can screw that up.

Do you think you’ll see it? Do you go to the movies?

I don’t go out. I haven’t been to a movie in a while, but I see them at my house. I’ll see it there. I watched “Barbie.” I can’t believe I watched “Barbie.” It’s just not my generation. I had nothing to do with Barbie dolls. I didn’t know who Allan was. I mean, I can sum it up. She says, “I don’t have a vagina,” and then at the end, “I’m going to go to a gynecologist!” That’s the movie to me. I mean, there’s a patriarchy business in there, but I missed that whole thing. Right over my head. But I think she’s fabulous, Margot Robbie.

How did your first streaming series, “Suburban Screams,” come about?

It was an offer from the company that produces it. They don’t want me to say “reality,” but it’s true stories. These are all true stories dug up by researchers, and the one I chose was a phone stalker because I connected to it. They’re creepy stories. I shouldn’t say this, but they’re shot on reality show budgets, which is a challenge. I did not [conduct the interviews]. I was there, but I was watching the interview.

You re-create this woman’s testimony of being stalked by a mysterious stranger with the suspense of a horror film, building real tension and menace. How did you find your way in?

I needed a really great actress [Julie Stevens], and I found her. That takes care of about 90% of my problem. This poor girl. Six years she’s been stalked, but they can’t find who it is. So I listened to her story. We hit the points that are going to translate into a visual story. Poor thing. And I remote-directed it, which was fun. That’s the way I’m going to do it now. I’m too old to run around, stomping around.

What did remote directing look like for you?

I [directed from] a chair in the front room where I play video games, where I watch basketball and watch the news. It was all set up so the big screen TV has the [live camera feed] through the lens. That’s all in Prague, coming to you right here in L.A.

After a 13-year break, what did it take for you to want to direct again?

A number of things. Sometimes I can’t tell you why it’s interesting to me. This phone stalker story was interesting.

How to get scary-close to 12 iconic L.A. film and TV horror homes

There’s a scene in your episode in which your protagonist, Beth, receives an unsolicited text of her stalker’s penis — taken from the driver’s seat where she’s sitting. It is chilling in the moment, and though there is often an innate sense of humor in your storytelling, it doesn’t blunt the horror of the situation; it makes it more real. But how did you get away with showing an uncensored picture onscreen?

They let me do it!

Did you get any pushback from Peacock?

First of all, the young lady who wrote the script put that in there. We were sitting there, listening to the real lady’s interview. I made a joke or something. And Amanda [Deibert] stuck it in. [Deibert is credited as creative consultant on the episode.] I thought, how am I going to do this? I’ve had this career since when, and now I’m photographing dick pictures? But we got it done and there it is.

Is that the first penis picture to make it into a John Carpenter film?

That’s correct. That’s the first one ever. Very proud of it. I’ve never thought I’d be doing something like that, but it’s what she experienced.

As executive producer, how much say did you have in the other episodes?

We looked at them all and said, OK, these are good. But the world of television is strange. You shoot something, you cut it together. Do you have any idea how many comments we get from these people? They pass it around for network notes. Everybody has notes. I don’t ever get notes like this [in features]. Some of them are crazy. And the thing is, they watch it on their computers or their phones and don’t watch the whole thing, or they’ll watch part of it and put it down and do something then come back and pick it up. No, no, no.

Did you have input into the crews and the other episodes’ directors?

No. We were told where to shoot. [But Prague] doesn’t look like America. Come on, guys! You don’t want to do a Viking movie or a Dracula movie, that’s the place for it. Not the suburbs. ... It is a different world. The people who run streaming, they’re not from the show business.

Does that mean you get the freedom that you want?

Yes and no. It’s different. They don’t demand power like the old timers do. But I’m glad I had the experience, to see that I have not been interfered with at all. I might [do it again]. It depends on the story and if I can do something with it.

Years ago you kept a big stack of scripts on your desk. Are you still actively looking?

It’s all for show! Everybody does the same thing in the movie business: they back into stories. You get a story and [financiers] know what they want to spend on it before it’s budgeted. I’ve done that too much. I’ve done it all my career. You back into it and you have to make it fit, and sometimes it doesn’t fit. I don’t want to complain. I shouldn’t be nagging. I should be happy! I want to be happy now.

Well, it’s your prerogative how you want to feel.

I should be very happy with it. They’re all wonderful people. It’s a wonderful business, a kind business. [Carpenter grins.]

The kindest business.

Yes, they take care of you, they’re sweet.

Have you been closely following the strikes?

I’m following it, but from afar. I don’t understand AI. I know that studios will hire an actor and say, “We own your image.” And that can be re-created by a computer and used anywhere they want. Other than that, [AI] making music — really?

Writers and actors on strike are forcing Hollywood to address deep-seated issues. The latest from the protests and what’s at stake on The Envelope podcast.

Last summer there was an AI-made song that mimicked the vocals of Drake and the Weeknd and went viral. [“Heart on My Sleeve,” which was recently submitted for the Grammys.]

Was it any good? That’s what counts!

So if one day there’s an AI-generated John Carpenter movie, you’d be OK with that?

Is it any good? Do I get residuals?

Well, that’s the thing. Perhaps not, right?

I’m not going to worry about that now. But it’s interesting. I hadn’t thought of that.

How interested are you in directing features these days?

Get the right one or the right budget — yeah, I’ll do it. I don’t want to work that much, though. Compared to music, it’s so different because music is the purest art form there is. You don’t have to talk about it, you don’t have to explain it. I can play it and somebody in Indonesia can just feel it. Across time, I can listen to Bach’s “St. Anne” and tears come to my eyes just like when I first heard it, it’s so profound. A human being wrote that. Wow. There’s no comparison to that in any other form. But unfortunately, I fell in love with movies, which is the craziest, silliest art form there is.

And a high-stress one at that. Looking back, how did you deal with that?

Not very well! I was a chain smoker, which had a terrible effect on my health. I was too stressed. I had to stop making movies for a bit. I had to have some space. You know, I am closer to the end than I was. I think about that now. I think about nothingness; what’s next. Anyway. I’ve got to tell you, I’m lucky as hell. I’m lucky.

As a master of horror, do you find it ironic that people who don’t necessarily watch horror don’t understand how life-affirming the genre really is?

Oh, yeah. That is what it’s all about.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.