How an untested, cash-strapped TV show about books became an American classic

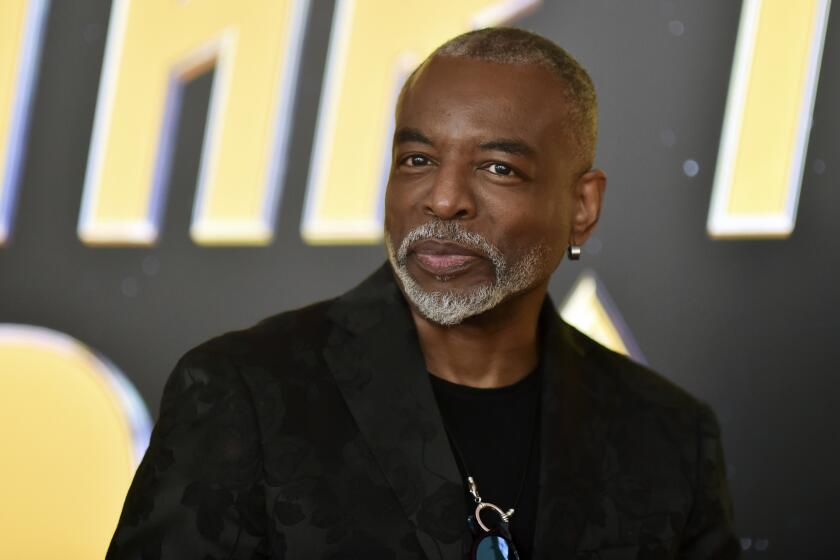

Jet-lagged and exhausted, LeVar Burton rallied his youthful energy as he exited customs at New York’s JFK airport and climbed into a waiting limo. He had just traveled from the Zambezi River in Zambia, where he had filmed a segment for the April 4, 1982, episode of ABC’s “The American Sportsman.”

The car made its way from Queens to Manhattan, dropping him off at Central Park. He was there to shoot the pilot for a new public television show aimed at encouraging early learners to love books.

The show was to be called “Reading Rainbow.”

He was not entirely sure what the job was, and certainly not aware that it would become one of his signature roles. It didn’t matter. The son of a former teacher and a passionate believer in learning, reading, exploring and growing, Burton was all-in on this new adventure.

“Everything about it just made sense,” Burton says, more than 40 years later. “It was about literature and the written word, it was about kids, it was about having kids discover the power of literature through the medium of television and that was why ‘Reading Rainbow’ was such a radical departure from other shows of its era.”

From the moment he first met the “Reading Rainbow” crew, Burton demonstrated not one iota of star attitude.

“He showed up, got out of the limo, and I said, ‘Hey, how are you?’” Cecily Truett, co-creator, head writer and producer on the show for most of its run, recalls. “He said, ‘Well, I just got off the red-eye, so…’ I said, ‘Well, what can we do for you? How can we make you comfortable?’ He said, ‘You know, I’d love to have a glass of orange juice and a toothbrush.’ And that was it.

“He walked right on to the set, he ran through his lines and for the next 25 years he was on the set, on time, with his lines memorized....”

“For 155 shows,” her husband, Larry Lancit, another of the show’s creators, producers and directors, added.

Burton had to hurry back from Africa to New York because a skeleton crew was waiting to shoot the pilot episode, including anxious documentarians Truett and Lancit and fellow creator and executive producer Twila C. Liggett, a onetime elementary school teacher who had realized TV was the ideal medium to reach and influence young children. If “Reading Rainbow” delivered on its promise that a children’s show focused on the joy and value of reading could be set in the real America rather than on Sesame Street or in Mister Rogers’ neighborhood, it would get the blessing from PBS.

It did the trick. This month marks the 40th anniversary of the national premiere of one of the longest-running children’s shows in the history of public television.

That pilot episode centered around the children’s book “Gila Monsters Meet You at the Airport” by Marjorie Weinman Sharmat and Byron Barton. It is about a young New Yorker whose family is moving to Arizona, and who faces the fear felt by any kid torn from the community he or she has known and grown up with to resettle someplace distant, almost alien. (Spoiler alert: No desert animals meet the young man and his family upon arrival.)

As was the case in every episode that followed, Burton played host, trusted friend and calming presence. He was the face of the show and its most visible advocate, which was needed, since Liggett was forever searching for funding to pay for the show’s ambitious storytelling and wanderlust. Having the charismatic, passionate host on every episode and advocating on behalf of the show to Congress, parent groups and elsewhere made Liggett’s job much easier. Burton stayed with the show even when he got a much higher-profile job, as Geordi La Forge on the syndicated “Star Trek: The Next Generation.”

Forty years after the launch of ‘Reading Rainbow,’ ‘Star Trek’ actor LeVar Burton is championing literacy programs for children with the documentary ‘The Right to Read.’

With the pilot shot — once the show got on the air, it actually was Episode 8 — all that was needed was the blessing, and partial funding, of the Corp. for Public Broadcasting (CPB), the private, nonprofit corporation charged by Congress to financially support PBS shows. Rev. Donald L. Marbury, at that time the vice president for programming at CPB, recalls the high-stakes meeting when Liggett presented the results of the pilot to him and his colleagues:

“In such meetings you couldn’t show too much enthusiasm or give too many positive signals because we were the Corporation, and we were bound by all kinds of processes and procedures. We did not have dollars to just say, ‘OK, we get it. Here, take the money.’ We had to go through panels, we had to go through outside groups and experts to come in and ratify what we thought were good ideas.”

And yet, because he remembered his own elementary school teacher decades before imbuing him with a love of books and reading, Marbury concedes, “When Twila comes in with this concept for ‘Reading Rainbow,’ you know I’m predisposed. I’m a kindred spirit. And so, she kind of had me from jump street, if you will. She had me at hello.”

Meanwhile, Lancit and Truett took a well-earned vacation to Puerto Rico, though their minds were elsewhere.

“Our whole future depended on whether we were going to do this thing or not because we were going to have to do 15 [episodes that first season],” Lancit remembers. “They wanted to show it in summer of ’83 and here it was January of ’82. So, we’re gonna have to really haul ass to get it all done.”

“We’re sitting on a balcony in Puerto Rico, overlooking the ocean and there was a tremendous rainstorm, when a big rainbow came across the sky and damned if the phone didn’t ring. It was Twila. She said they loved it at CPB and basically authorized the funds,” Lancit recalls. “So, it looks like we’re going to get started.”

Much of what became the template for “Reading Rainbow” — built around Liggett’s ideas that the show should encourage early readers to read to learn instead of simply learning to read — had already been decided earlier in the process, after the Lancits, Liggett and a few others had received the initial OK from CPB to develop the pilot.

“We knew what we wanted,” Lancit says. “If there was going to be a feature book and some sort of adaptation of that book, we decided that there really needed to be some sort of touchstone in real life that made the book come alive, by doing some sort of real-life experience that you can attach to the story that’s in the book. That was the genesis of what we called our field segment. And then we said, ‘Well, how do we introduce additional books?’ And we said, ‘Let’s do book reviews,’ and so we came up with the idea to have kids at the end of each show review books that were similar in scope, or message, or story.”

Aside from host LeVar Burton’s signature line before the young children would tout their favorite book — “But don’t take my word for it” — the show was different each time, which kept it fresh. A new feature book was showcased every episode, read by various known and unknown voices.

And unlike most other shows for kids, whether on PBS, commercial channels or, by the mid ’80s, cable, “Reading Rainbow” had no fixed set. Instead, it would travel — often to Southern California, in part to be close to LeVar Burton’s home — as well as across the country, around the world (when budgets allowed, which wasn’t often) or just across New York City, in pursuit of the right expert, the ideal setting, the most photogenic location to shoot a field piece. And, of course, there were boys and girls of all races and ethnicities to recommend additional reading options.

Among the notables who narrated the Feature Book that first season were actors Madeline Kahn (“Bea and Mrs. Jones”), James Earl Jones (“Bringing the Rain to Kapiti Plain”) and Lauren Tom (“Liang and the Magic Paintbrush”), and singer Lou Rawls (“Ty’s One-Man Band”).

One other book featured that first season was “Arthur’s Eyes,” read by a pre-controversy Bill Cosby), which author Marc Brown remembers as a key moment for him, “because that’s when Arthur started to gain traction with teachers, librarians, kids.”

In fact, it wasn’t long after that book was featured on “Rainbow” that Brown was approached by PBS about adapting his Arthur stories into an animated series. WGBH Boston producer Carol Greenwald emphasized that the aim of the series was to encourage kids to read.

That was different from some of the other offers he’d received to bring his popular aardvark character to TV. “I had had two other inquiries about Arthur on television, but it was a Saturday morning kind of thing. I would’ve had no control over what would happen to Arthur; they could put a gun in his backpack. And I didn’t want that to happen.”

Indeed, while PBS Kids, as it’s known now, was and remains a safe and welcoming destination for youngsters, it wasn’t the only place for kids to be entertained by TV. Shows aimed at young viewers aired on the big networks as well as on local stations, especially on Saturday mornings, but also in the afternoons, after school.

Until the passage of the Children’s Television Act in 1990, which wasn’t fully implemented until 1993, broadcast TV was largely unregulated — or, more accurately, was self-regulated.

That’s how a show like “He-Man and the Masters of the Universe,” which also began in 1983, got on the air. Based on the He-Man toys from Mattel, the series’ blend of product and programming spurred loud objections from parent groups, TV watchdogs and others before becoming a huge hit on commercial TV.

Sen. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) has waged a career-long crusade to hold broadcasters accountable for what they aired, particularly to children. He recalls, not at all fondly, his battles with President Ronald Reagan’s Federal Communications Commission, under the leadership of Chairman Mark C. Fowler, which followed the Reaganomics model and rescinded all of the regulations governing children’s TV.

So, when Markey, then a member of the House of Representatives, managed to pass a bill in 1984 that reinstated and even strengthened the rules that had formerly been in place, it was no surprise that the president vetoed it. Markey got it passed again during the first President Bush’s term, and he too refused to sign it, twice. It wasn’t until Democrat Bill Clinton became president and appointed his own FCC chairman, Reed Hundt, that the Children’s Television Act finally became law.

Even now, 30 years later, Markey remains bitter about the fights and compromises necessary to pass meaningful legislation regarding kids’ TV. Markey says the Reagan and Bush administrations “showed a deep-seated obeisance to the broadcast industry, almost genuflecting at their every whim, notwithstanding the harm that was being done to children across the country.”

It was in this environment that “Reading Rainbow” launched, a co-production of Nebraska Educational TV in Lincoln, where Liggett was based, and WNED in Buffalo, which was involved in the show from the beginning as well. Premiering any show is challenging, but it was logarithmically harder for this show, which had no fixed location, needed rights to multiple books for each episode, had to fight hard, particularly in the early seasons, to get placement on local PBS stations, and do all of it under tight budget constraints.

As far as figuring out which books to feature, Truett remembers coming up with basic standards, in collaboration with Liggett and some of the academic advisors the producers consulted regularly.

After 25 seasons, the animated children’s program came to an end Monday with a glimpse of the characters as adults. Here’s how it came together.

“Is it telegenic? Does it lead to an adventure that would excite the viewer? Is it kid-friendly? Is it about dinosaurs? (That’s a no-brainer.) Did it meet our diversity standards? Were there books that were reflective of children of all colors and cultures? … There were many, many standards for what got selected as a feature book.”

Then there was the matter of locking down the rights to spotlight the books, which was predictably agonizing, at least in the first season. The hard work of securing rights, and money, fell to Liggett. She chuckles now at the memory of dealing with skeptical publishers for rights to the book, since by the end of the first season, publishers couldn’t do enough to get their books on the show.

But in 1982, as the first season of shows was coming into focus, it was still an untested, unproven proposition when Liggett went to Simon & Schuster to get rights to adapt “Gila Monsters” for TV.

The Simon & Schuster executive couldn’t understand why her company would let a TV show have rights to the book; for publishing houses, the so-called “boob tube” was the enemy of reading.

“When we first started approaching book publishers to tell them about this and secure these rights, we were initially greeted with a lot of suspicion and questions like ‘What’s this all about?’” Marc Bailin, Truett and Lancit’s attorney who helped negotiate book rights, remembers. “Within a few years, the publishers were clamoring to have their book be a ‘Reading Rainbow’ book.”

That’s no surprise since, from the start, having a book featured on the show “increased the book sales of a lot of those titles markedly,” Bailin says.

By the time “Reading Rainbow” aired its final episode on Nov. 10, 2006, it had produced 155 in all, each with the same essential structure, each different in content from the other 154. It taught multiple generations of young children to love to read, to explore and keep their eyes open to new experiences, new people, new ideas.

Never the icon that its friendly rivals “Sesame Street” or “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” were, and drawing nowhere near the audience numbers of cable TV behemoth Nickelodeon’s hits, “Reading Rainbow” was still a show watched and beloved by early readers, their parents, teachers and others.

As Burton explains, “We recognized the impact on the audience and we leaned into it. It made sense, we were there creating content for children to enhance their minds, hearts and souls, right? And given that opportunity, we didn’t want to squander it.”

This article is adapted from the forthcoming book “Butterfly in the Sky: ‘Reading Rainbow’ and the Endless Challenge of Entertaining While Educating Our Children,” by Jonathan Taylor. He is a former television editor for The Times.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.