‘American Born Chinese’ began as a photocopied comic. For its creator, the journey has been ‘surreal’

For cartoonist Gene Luen Yang, the lead-up to the premiere of “American Born Chinese” has been “very surreal.”

Whereas the promotional cycle for one of his books might involve appearances at events like librarian conferences, special advanced screenings of the TV series have taken Yang from the Bay Area to New York and even the White House.

Attending the Asian American, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander Heritage Month celebration hosted by President Biden, which featured a screening of “American Born Chinese,” earlier this month “really felt like I was living somebody else’s life,” said Yang during a recent video call. “It felt like I was playing a virtual reality video game.”

Based on Yang’s award-winning graphic novel, “American Born Chinese,” which premieres Wednesday on Disney+, follows Jin Wang (played by Ben Wang), a teenager that just wants to fit in, play soccer and win over his crush. But after reluctantly befriending his new classmate Wei-Chen Sun (Jimmy Liu), Jin gets pulled into a battle over heaven between mythological gods.

Executive producers Tze Chun and Brendan Hay discuss Gizmo, Mr. Wing and reclaiming “the somewhat throwaway origins” of the Mogwai in their new animated show on Max.

From showrunner and executive producer Kelvin Yu, the fantasy coming-of-age action series has made some very noticeable changes from its source material. But Yang, who also served as one of the show’s executive producers, insists that the “spine” of his original story remains intact.

It’s a story about “a young man who is struggling with his own cultural heritage, with the way he looks, with the language his parents speak, [who] becomes friends with this immigrant kid,” said Yang. “And it turns out that this immigrant kid isn’t just from Asia, he’s actually from Asian mythology. The main character eventually learns to accept himself through this friendship.”

That the adaptation retained that core premise was one of the most important things to the author. Another was that the show represented the three different worlds that the story unfolds.

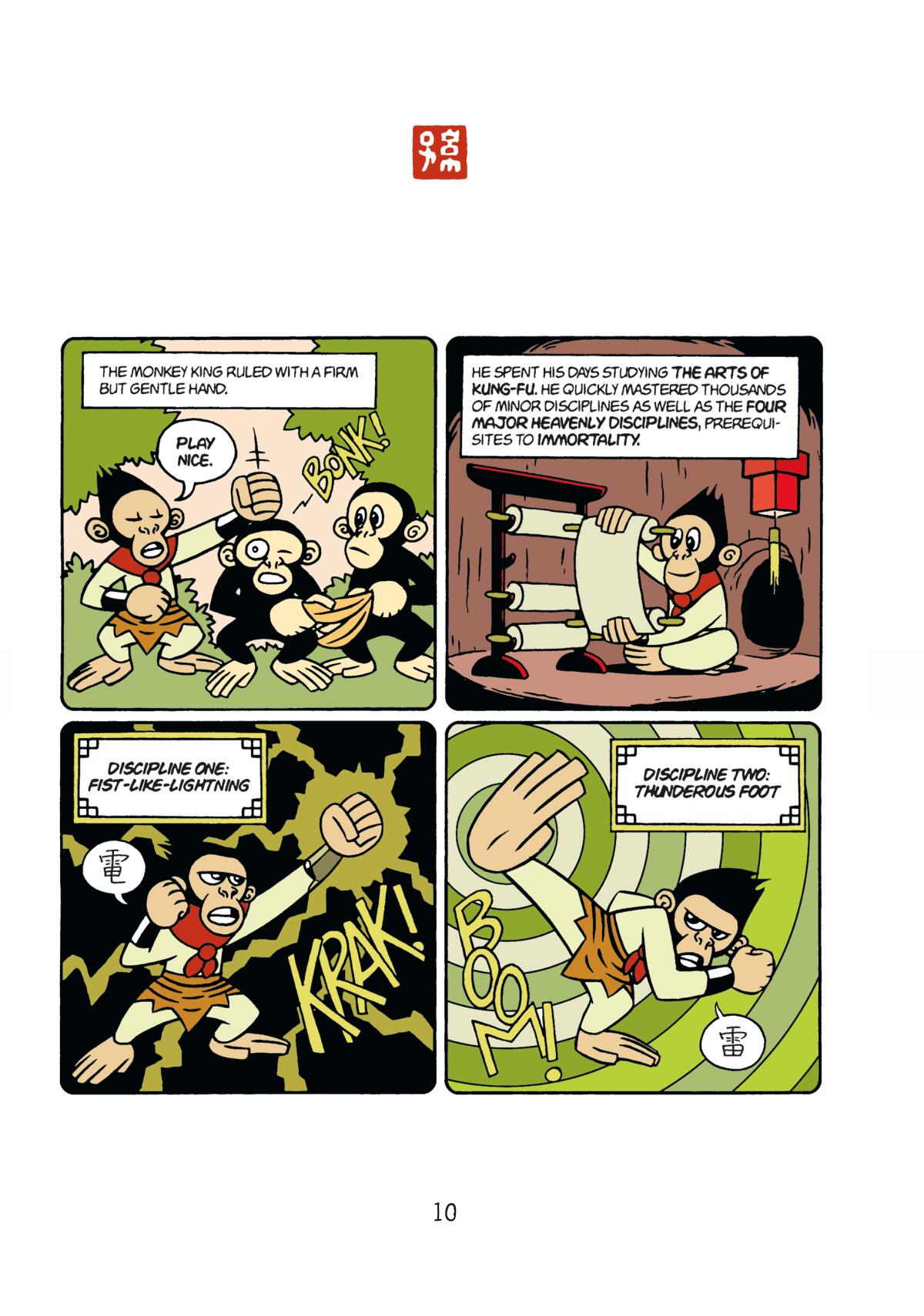

The graphic novel features three seemingly distinct narratives that are eventually revealed to be interconnected. One storyline follows Jin Wang, who struggles after he transfers to a school where there is only one other Asian American student. Another is the tale of the Monkey King, a mythical god from the 16th century Chinese classic “Journey to the West.” The third is about a popular blond-haired, light-eyed teen jock who is embarrassed of his visiting cousin, who is an amalgam of every racist Chinese stereotype perpetuated by mainstream culture.

Yang originally started working on “American Born Chinese” in 2000. He’d been making indie comics for around five years at that point, after graduating college in 1995. Although his work always featured Asian American protagonists, he had yet to make identity a central part of the story.

For AAPI Heritage month, we’ve got you covered: R. F. Kuang on her scandalous novel ‘Yellowface,’ Jasmin ‘Iolani Hakes on her debut, ‘Hula,’ plus 6 other books.

“I knew at some point, I wanted to do some kind of a comic book project where that was at the center,” said Yang. “Because my own cultural heritage has been such an important part of how I found my place in the world, I wanted something where that was the focus.”

Based on his personal experiences, Yang had to unpack memories like being bullied as a kid and being made to feel like an outsider for being Chinese American. But he says working on the book was “really cathartic.”

“I remember feeling a real sense of release as I was working on the project, especially when I was done with it,” said Yang. “I think this is true of a lot of authors and artists — we’re trying to do self-therapy when we’re working on these different projects. That was certainly true of me and ‘American Born Chinese.’“

Like his other early work, “American Born Chinese” was self-published. After drawing an issue, Yang would head to a shop to make photocopies, staple them together by hand and sell them at local conventions and comic stores. He was eventually put in touch with First Second Books, and the publisher expressed interest in releasing the comic as a fully colored graphic novel. First Second released its edition (colored by Yang’s friend Lark Pien) in 2006.

“American Born Chinese” became the first graphic novel to win the Michael L. Printz Award, which recognizes books written for teens, as well as the first graphic novel to be a National Book Award finalist. It also won an Eisner Award, the comic book industry’s top honors, and was included in a number of best-of lists for 2006. Championed by librarians and teachers, the book is even taught in some classrooms.

Yang admits that early on, he had a lot of hesitation about an “American Born Chinese” adaptation. One of his concerns was specifically about the satirical cousin character, whose name evokes a racist slur (that this writer and Yang both avoided saying aloud over the course of the interview), and how he would translate from page to screen.

“I was really worried that if it ever got adapted, that clips of this cousin character would show up on YouTube completely decontextualized and it would be the exact opposite of what I was trying to do in the book,” said Yang.

The Disney+ series does not include the cousin character or his narrative, and instead introduces a storyline about a fictional popular sitcom, called “Beyond Repair,” that features a stereotypical Asian character, Freddy Wong (played by Ke Huy Quan), who has a catchphrase and is often the punchline to a physical gag. Clips poking fun at Wong circulate as viral memes on social media to mock others. Themes around representation in media and how people are affected by it are more directly addressed through the character.

Among the other changes is the show’s present-day setting, the inclusion of more Chinese deities and the additional storylines involving Jin’s parents.

“The book is a ‘me’ story,” said Yang. “It comes from me. It’ll always be there. And the show uses the book as a launching pad to become an ‘us’ story. It’s a whole bunch of us all contributing and I’m really thankful I got to be a part of that.”

Another shift that audiences who are familiar with the graphic novel might notice is that in the book, Wei-Chen is introduced as being from Taiwan, whereas in the TV series, he is from China.

“In both the book and the show, we don’t really specify what Wei-Chen necessarily identifies as,” said Yang. “In the book, it does state that he’s from Taiwan, but he never uses the word Taiwanese.”

Yang acknowledges the delicate nuance, explaining that some families that trace their ancestry back to Taiwan — like his — identify as Chinese, while others — like Yu’s — identify as Taiwanese. He adds that back when he was a student in the 1980s, when the graphic novel is set, many of the immigrant kids he met came from Taiwan.

Plus, “in my timeline in my head for the book, Wei-Chen went to Taiwan for a while before he came to America,” said Yang. “He went from Heaven to Taiwan to America, but I never specified that [in the book]. Whereas in the show, things are much more immediate. He makes the jump and kind of ends up in the middle of an American neighborhood.”

The series arrives at a time when Asian and Asian American stories have become more prominent and celebrated in mainstream entertainment. The show’s cast includes Academy Award winners Michelle Yeoh and Quan from the Oscar-winning “Everything Everywhere All at Once.” Other recent hits centering Asian characters range from the animated “Turning Red,” to the superhero “Ms. Marvel” and even the rom-com “To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before.”

But it is also a time when books, particularly those that acknowledge racism or the existence of LGBTQ+ people, have increasingly been targeted by right-wing activists, politicians and parents for censorship and removal from classrooms and libraries. Yang says that even “American Born Chinese” has seen an uptick in challenges recently.

For Yang, one of the most egregious examples has been the challenges against Jerry Craft’s Newbery Award-winning graphic novel “New Kid.”

“It’s such a gentle and good-humored book,” said Yang. “It deals with a lot of tough topics about race, but it does it in such a gentle way. In a lot of ways, I feel like the pushback on that book kind of delegitimizes, to my mind at least, the entire endeavor.”

And at a time when so much information is instantly available on “devices we all keep in our pockets,” Yang believes books are absolutely the wrong target.

“A book is so hard to make,” said Yang. “It’s very, very slow and painstakingly created information. And in a world of very fast information, you want as much of that slow and painstakingly created information as you can get because more often than not, the slow information is the high-quality information. So for people to come after books, in this day and age, it’s the exact opposite of what our world actually needs.”

‘American Born Chinese’

Where: Disney+

When: Any time

Rating: TV-PG (may be unsuitable for young children)

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.