Anyone who has heard the R&B classic “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” knows the song is about a lover receiving news about their cheating significant other through whispered conversations and gossip.

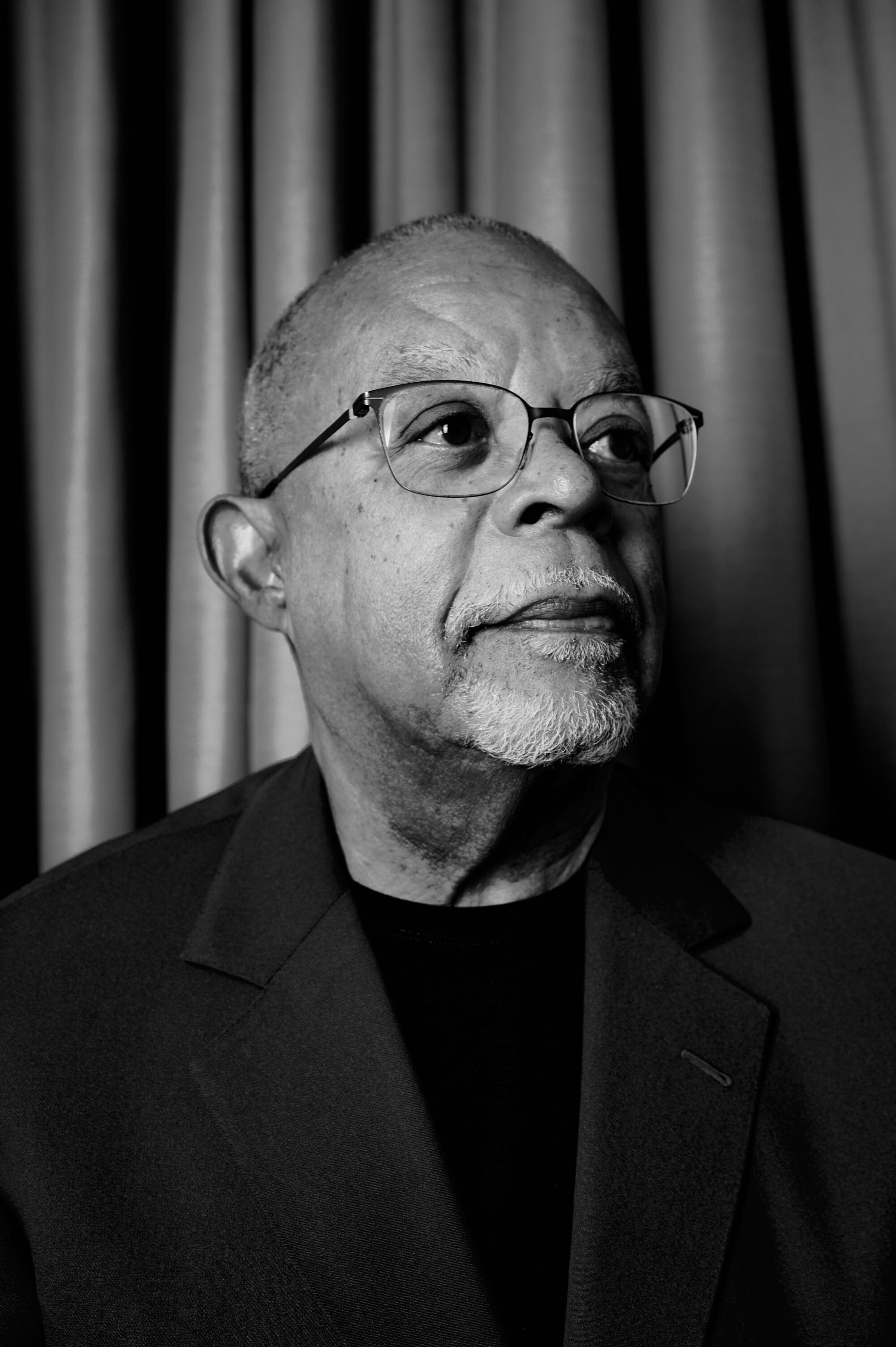

But renowned scholar and television host Henry Louis Gates Jr. (“Finding Your Roots”) is ready to put another spin on the phrase, shining a spotlight on the social, religious and intellectual networks through which Black people have fostered a thriving Black culture against significant odds.

“Black Americans have with grace, ingenuity and imagination created a world on the other side of the color line,” Gates proclaims at the beginning of his docuseries “Making Black America: Through the Grapevine,” premiering Tuesday on PBS. Gates adds that it’s a world “with its own values and rules” and this cultural grapevine “is as old as the American Revolution.”

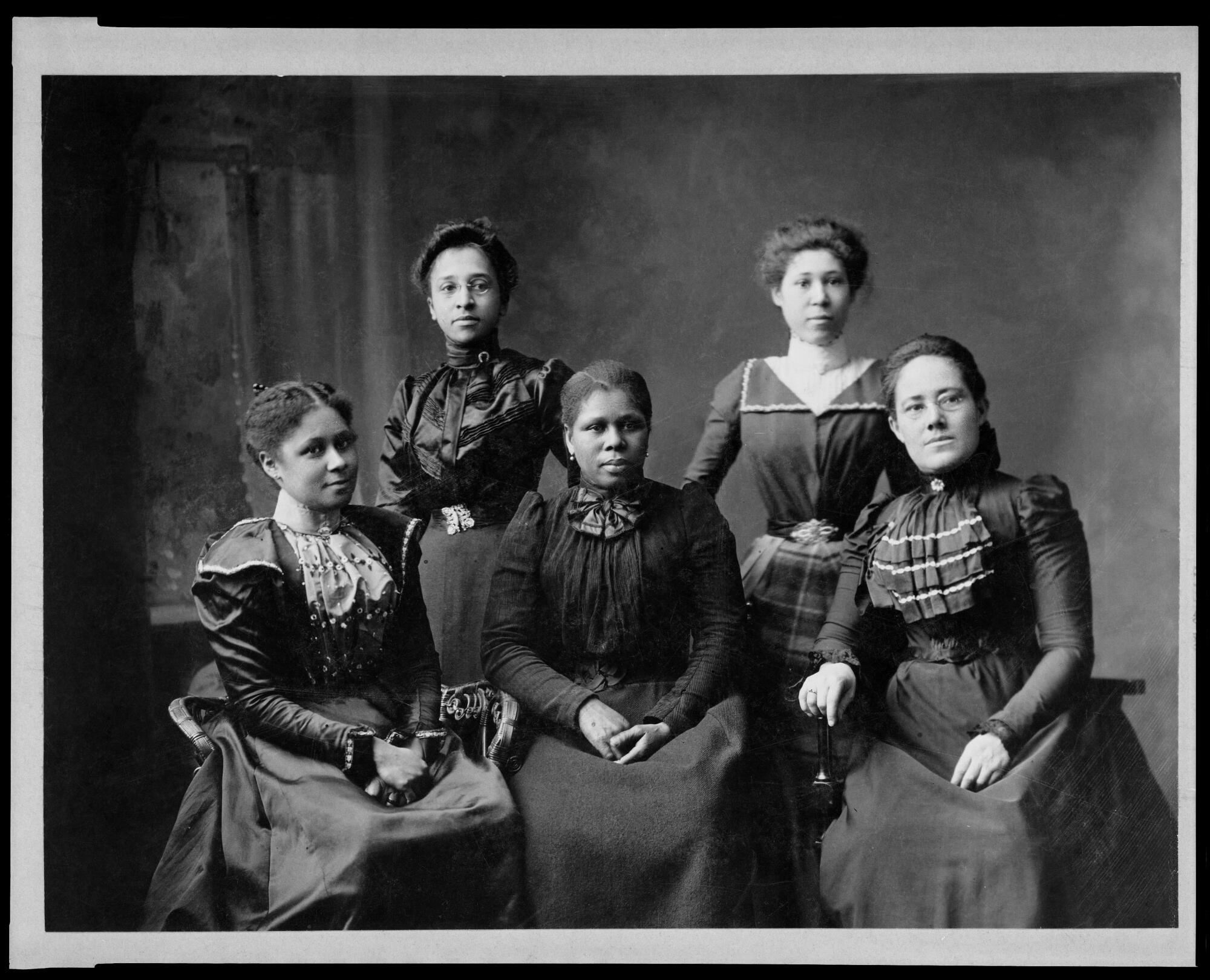

The four-episode project examines the founding of the Prince Hall Masons in 1775, explores the beginnings of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and moves to present-day looks at the Black Lives Matter movement and Black Twitter. Gates said the institutions were formed not only for survival but for the free expression of Black love and joy.

The new PBS series from Henry Louis Gates Jr. is a forceful argument against the popular image of devout Americans as white, rural and conservative.

The series is the latest documentary Gates has produced for PBS; others include last year’s “The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song,” exploring various layers of African American history.

Gates said this project is designed to reach Black and non-Black viewers alike: “It’s a clarion call to young Black people, to remind them that they come from a noble tradition of culture bearers and culture seekers. I’m targeting it for the Black community to bolster self-esteem but also to our white, Asian and Latino brothers and sisters who don’t know the true history of our people.”

“Making Black America” arrives at a moment when political divisiveness, the debate over critical race theory and the continuing influence of white supremacy have ensured Gates’ stories of race and racism in America are as relevant as ever. The project also represents a counterpoint to numerous film and TV projects in the past several years, such as HBO’s “Watchmen” and “Lovecraft Country,” Amazon’s “Them” and “The Underground Railroad” and the Oscar-winning short film “Two Distant Strangers,” which feature scenes of Black people being killed, tortured and traumatized in what many observers have classified as “black trauma porn.”

In a Zoom interview last week, Gates discussed the timing and the goal of the series, his thoughts about the current racial climate and why “Making Black America” is the most political docuseries he’s ever done.

This project is a relief coming after so many films and movies that have focused on Black pain and anger. What is the primary message you’re communicating?

I’m asking and answering the simple question which every African American understands as soon as I say it in a lecture hall: What did our people do when the curtain of white supremacy came crashing down? Did we sit around and say, “Woe is me?” Did we sit around and cry? Was protesting all we did? No! We re-created the worlds from which we were excluded, just like our Jewish brothers and sisters did. Our Black social networks go back to pre-USA, before the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

How do you feel this project will be received, especially when race is such a volatile topic?

The timing is perfect because I want to educate Americans about how much agency Black people have exhibited and possessed since slavery time. Our people created a world-class culture — the spirituals, the blues, ragtime, jazz, folklore. We built a first-class civilization.

Racism and the struggles of Black people are certainly a part of the series, but it is not the primary focus. The tone is one of uplift.

There have been a zillion documentaries about Black political protests. I’ve made documentaries about those, and we do touch on it here. If you ask Hollywood about what Black people do, the answer would be, “Protest, protest, protest.” But we also talked about joy, ambitions, hopes and dreams. We told each other stories. Me and my producers wanted to re-create the world we grew up in.

If you had a monitor in an average Black home 24 hours a day, how much talk would be about white racism? Not much, unless the KKK had burned a cross in town. We are human beings. The political goal of this series is to show how resilient our people are under the most adverse of circumstances. It’s a counterintuitive way of making a political statement. This is the most political documentary I have ever done. It’s registering the complexity of Black people, and so many documentaries reduce us to reacting to white supremacy.

“Them,” about a Black family fighting racism and supernatural forces in the 1950s, includes warnings about its graphic depictions of racist violence.

It’s been more than a decade since the furor that was sparked when you were arrested by a Cambridge police officer who thought you were breaking into your own home. Then-President Obama arranged a “beer summit” with himself, you, the arresting officer and Vice President Biden. What is your perspective on that incident today?

You know, that’s like a footnote to my life. It was an aberration. I want to focus my energies on the least fortunate of our people. I’m more concerned about bringing justice to the people who this kind of thing happens to every day. Our prison system is disgusting. The percentage of Black people in our prison system is disgusting. I am concerned about police brutality.

When Donald Trump was president, you stated that you did not feel he was a racist.

I said that because I had friends who knew Donald Trump — Black people. I had decided like any scholar to give him the benefit of the doubt. But he is an opportunistic, anti-Black racist. I don’t know what he believes in his heart, but I know what he did and what he said, and what he did was absolutely racist. He realized he could beat that drum and hum that tune of white supremacy.

I’m always intrigued by how you continue to find new aspects of Black culture to explore.

My filmmaking partner, Dyllan McGee, and I have 10 documentaries outlined. Right now we’re working on the history of gospel music and the history of Black preaching. We want to do the African American Civil War, the history of Blacks and Jews, the Great Migration. I happen to be in the position to tell the story of Black people over a variety of media. That’s something I really thank God for every day of my life.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.