What does it mean to say the NBA had a drug problem in the 1970s and 1980s?

In Episode 8 of “Binge Sesh,” hosts Matt Brennan and Kareem Maddox examine recreational drug use in professional basketball in the Showtime era. Zooming in on the depiction of Spencer Haywood in HBO’s “Winning Time” and zooming out to the U.S. government’s war on drugs, we deconstruct the rhetoric — from politicians, the press, even players — that shaped perceptions of the NBA and explain how systemic racism turned a health crisis into a moral panic.

Listen now

Matt Brennan: So, Kareem, what do you know about Len Bias?

Kareem Maddox: Len Bias was supposed to be the next NBA great. He was drafted by the Celtics, supposed to take over for Larry Bird. I think it was in ’86. And the Celtics general manager at the time compared him to Michael Jordan, but taller and with a better shot. Pretty shortly after Len Bias got drafted, he attended a party and I think overdosed on cocaine and passed away.

Brennan: Yeah. So in 1986, two days after being drafted second overall by the Boston Celtics, college basketball star Len Bias died of a cocaine-induced heart attack. But that’s not actually the whole story. Abdul Malik, who wrote a piece about the history of the NBA’s recreational drug use policies for Jacobin magazine last year, told me about the huge ripple effect of Bias’ death.

Abdul Malik: Len Bias’ death was leveraged into an escalation of the war on drugs that was frankly disastrous for many already at-risk communities. He became a poster child for the dangers of drug abuse. That was really the culmination of everything you see at the beginning of “Winning Time,” which is the introduction of drugs, and players engaging in substance abuse, at the beginning of the ‘80s. And it sort of all came to a fore with Len Bias and then everything that happened after it was, you know, really like the, the war part of the war on drugs.

Brennan: Its official name was the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, and it was signed into law four months after Bias died. One of the things that the law establishes is something that we’ve become, I think, sort of familiar with, which is this idea that there’s a threshold quantity of drugs that if you possess more than that amount, you risk incarceration. It also establishes mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses. And the key thing to keep in mind here is that in both cases, there was a double standard in the law applied to crack cocaine versus powder cocaine.

Malik: The Len Bias law specifically ended up targeting, through its specific policies, like the difference between crack and powder cocaine, things like that. It was targeted to effect an attack the inner cities, which is nuts because he wasn’t even representative of those communities. He was part of a very emergent Black middle class of that era. So a lot of the policies in the Len Bias law were disingenuous even in terms of how they framed Len Bias’ background.

Brennan: And the other thing that really freaking gets my goat is that this bill was rushed through. There was no committee set up to analyze it. There were no hearings. It was literally just, like, built on a bunch of rumors and racist assumptions.

Maddox: So whoever wrote this bill found it advantageous to slap Len Bias’ name on it in the midst of this tragedy that probably, you know, shook the country.

Brennan: The way Abdul explained it to me, the rhetoric about drug use in the NBA in the 1970s and 1980s reflects the conversation that’s being had in the wider culture. And in both cases, that conversation was rooted in systemic racism and conscious and unconscious bias. So the passage of the Len Bias law in 1986 is sort of like the crystallization of that intersection.

Malik: The relationship between drug use and athletics, and moral panic over black people and drugs, has to lay into this. And that’s where a lot of the ideas behind it came from because there was a large amount of drug use in the ’80s, particularly cocaine usage, in the NBA. However, it was never quite framed as an issue of health. It was framed as an issue of morality, right, which is the most troubling thing. And an issue that I would argue that mostly white players escaped the five major bans and suspensions that were handed down to players for drug use were all Black players. It wasn’t until 2004 that a white player was suspended due to use of a banned substance.

Brennan: We’re going to use this episode to break apart that argument that the drug problem was the most serious problem that the NBA faced in that era. Meaning we’re going to deconstruct that assumption.

Maddox: OK.

Brennan: It doesn’t mean that we’re going to completely debunk it. It does mean that we’re going to complicate it and put it in context and try to deal with why it’s a little bit more thorny than just saying the NBA had a drug problem.

Maddox: Sure. OK. I would like to do that.

::

Brennan: Welcome to “Binge Sesh,” where this season we’re diving into the stories behind HBO’s “Winning Time,” the saga of the Showtime-era L.A. Lakers. I’m Matt Brennan, television editor of the Los Angeles Times.

Maddox: And I’m Kareem Maddox, professional basketball player and podcaster.

Brennan: OK. So what has been the message about drugs in the NBA that we’ve gotten from the basketball experts we’ve spoken to this season?

Maddox: Sure. So the experts say that the league at the time was suffering from the perception that a ton of the players were using drugs recreationally, but they also said that that was just kind of the ’80s and it wasn’t even that unique to the NBA necessarily. Here’s what Jeff Pearlman, who wrote the book on which “Winning Time” is based, had to say about that.

Jeff Pearlman: It was a cocaine era, first of all. I mean, coke was the party drug back then. And the NBA was a party league still, especially heading into this sort of era.

Maddox: I think earlier in the season we talked about, we use the quote from, a former NBA player who said like 75% of players recreationally used cocaine in the early ’80s, I think it was. Most people just assume that it’s true that a lot of players were using drugs in the NBA.

Brennan: Like even that number you cited — the 75% number — I don’t know that it’s necessarily fair to extrapolate from one anonymous player’s memory or guesstimate.

As we’ve discovered in our research for this season, there’s a proliferation of stories in the press about drug use in the NBA in the 1970s and 1980s. But one of the first things that starts to become apparent when you dig beneath the surface of those reports is that there isn’t actually a lot of like solid quantitative peer-reviewed scientific data. It’s all pretty anecdotal. And the ranges that you see presented are anywhere between 40% and 75%. That’s a huge difference.

Maddox: A long time ago, I must’ve been like 9 or 10, and my aunt said something to the effect of, like, someone asked if I wanted to play basketball when I grew up. And she was, like, “No, he doesn’t want to do that,” because that’s not something you aspire to. Like, you don’t want to be an NBA player. ‘Cause that is synonymous with drugs and the lifestyles that aren’t approved of. Like now, looking back on it, that was just the prevailing sentiment. Yeah, I think it’s now just become one of those accepted things that everyone’s, like, “Yeah. The drugs in the ’80s in the NBA.”

Brennan: Right? The notion that drugs were a quote unquote problem for the NBA hinges on a number of assumptions or fixed ideas. When a culture tells itself a story enough times over a long enough period, it can see being as accepted fact. And one story that is central to our understanding of what’s going on in the NBA in this era is the U.S. government’s war on drugs.

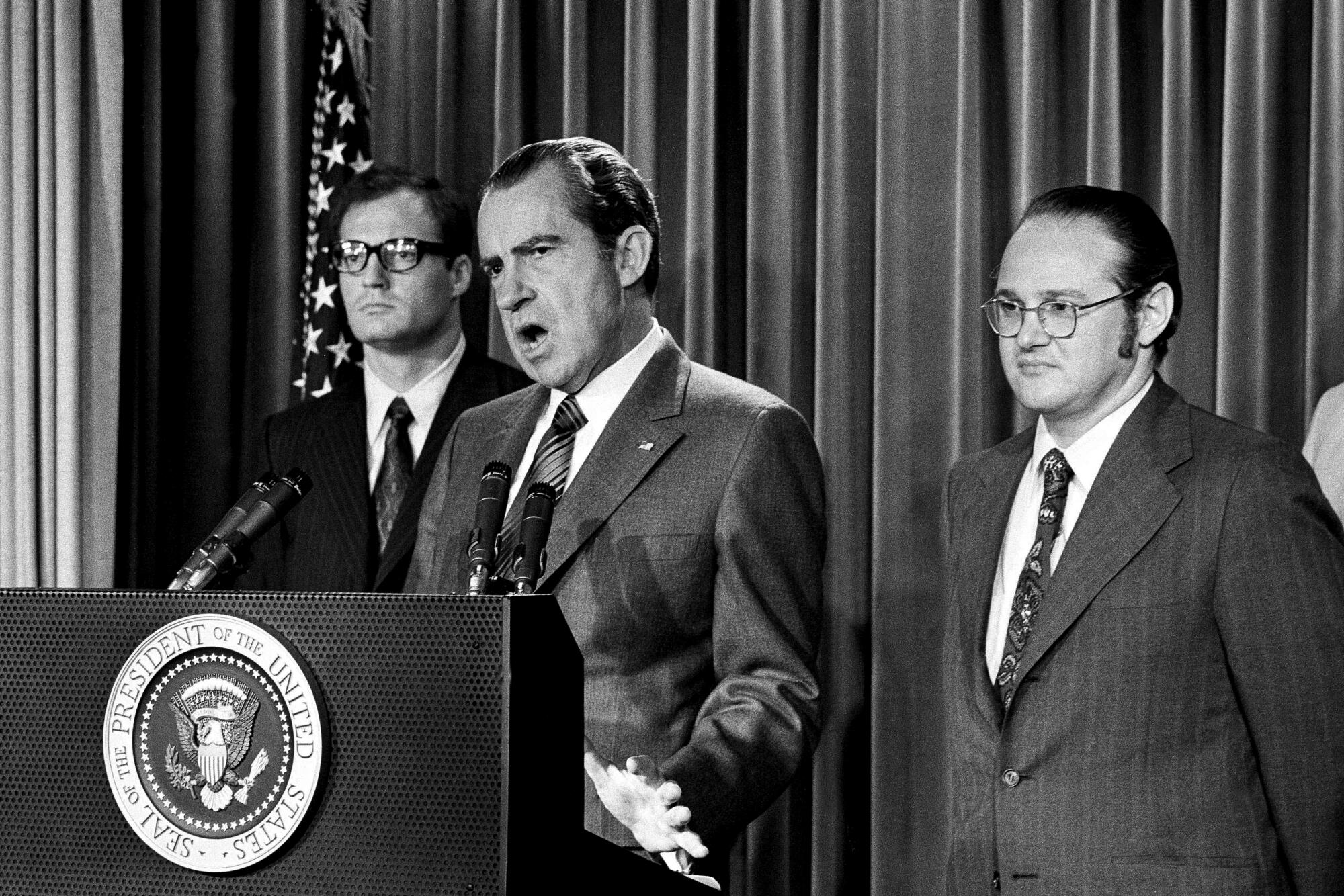

So the first thing to know is that this is not going to be a comprehensive history of the war on drugs. Anti-drug laws in the United States date back to the 19th century with anti-opium laws targeting Chinese immigrants. The key date to know for our purposes is 1971. That’s when President Richard Nixon gave a speech declaring drug abuse America’s public enemy No. 1. That’s where we get the phrase. Richard Nixon literally declared an official war on drugs.

[Clip of Nixon’s speech: America’s public enemy No. 1 in the United States is drug abuse. In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive.]

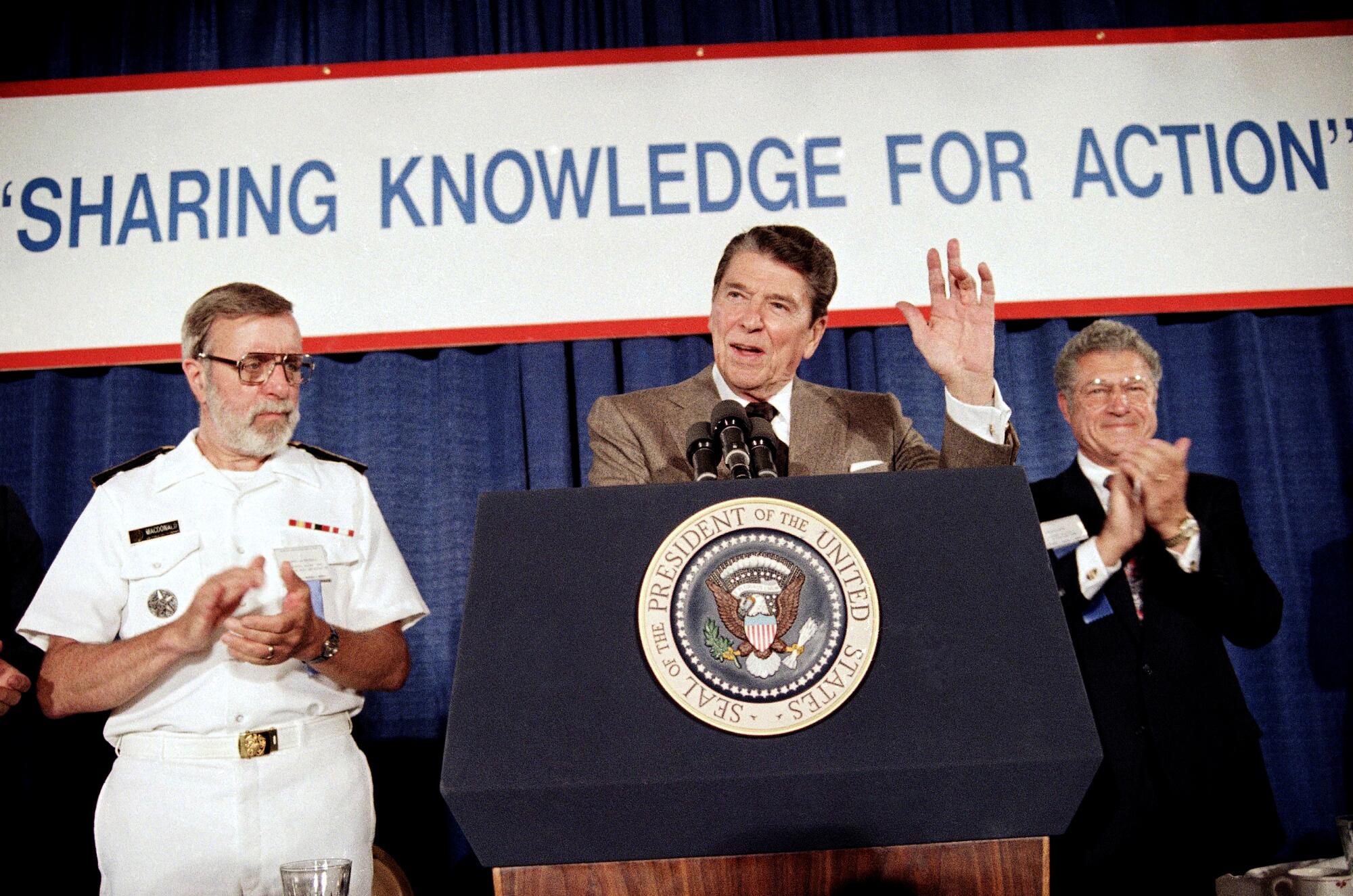

Maddox: I had always associated the war on drugs more with Reagan than with Nixon, which I guess makes sense given that Reagan was the president who signed the Len Bias law.

Brennan: I think you’re right in that association. The enforcement apparatus that grew out of Nixon’s declaration of war expanded during the Reagan years and continued through the Clinton years and beyond. We’re still experiencing the reverberations of its disproportionate effect on Black and brown communities.

Just to cite one statistic that made my jaw drop: A Vox story from 2016 compared drug use rates and drug arrest rates between white and Black Americans using data from 2013. While white and Black people were about equally as likely to have used drugs in the past month, Black people were arrested two and a half times as frequently and served longer sentences.

Abdul Malik talked to us about how you can see these kinds of patterns in the NBA too.

Malik: The NBA is almost like a microcosm of greater American culture, and obviously it’s like a fairly high point in American racial tension. And then you’ve got this explosion of popularity of basketball coming out of — a big part of it does come out of the Showtime Lakers. It was the first real image crisis. The league had during its shift from a majority-white to majority-Black league — that demographic shift in terms of the makeup of the players happened absurdly fast.

Brennan: Rachel Laws Myers, the author of “Race and Sports,” underscores the connection between racist stereotypes that were prevalent in the culture at large and perceptions of the NBA at this time.

Rachel Laws Myers: What I will say in terms of sports, I think all that whole era, right, adds to a stereotype, a perception that, you know, where do drugs come from and who’s doing drugs and what did they look like? And really that came down to, oh, people who do drugs, sell drugs, buy drugs are Black folks.

Brennan: OK. So we’ve set up the big picture. Now I want to zoom in on what we actually see in “Winning Time” and on the real-life Showtime Lakers.

Maddox: Can we do that after the break?

Brennan: Yes. I definitely need a break, and I’m sure our listeners do too. We’ll be right back.

::

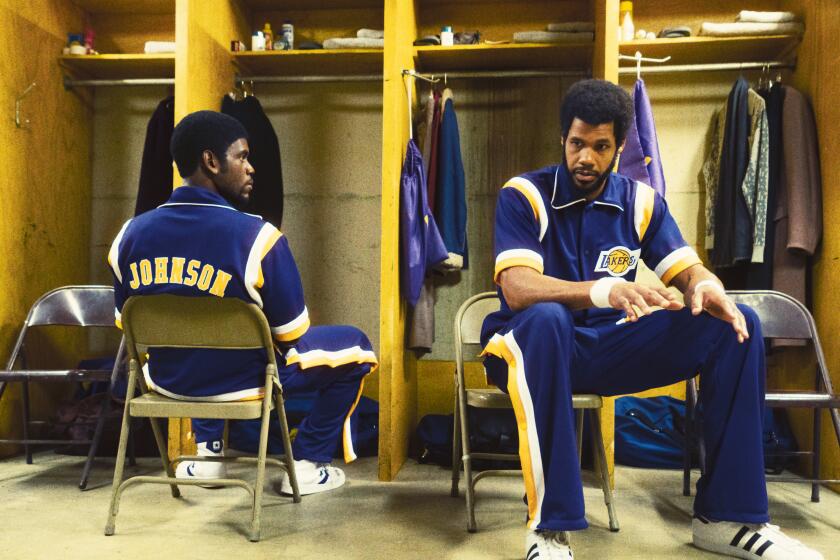

Brennan: Welcome back to “Binge Sesh.” So, Kareem, in Episode 8 of “Winning Time” we have our first encounter with drug abuse. Who is the player on the Showtime Lakers that we see in Episode 8 using drugs?

Maddox: Yeah, that would be Spencer Haywood.

Brennan: What can you tell me about the real-life Spencer Haywood?

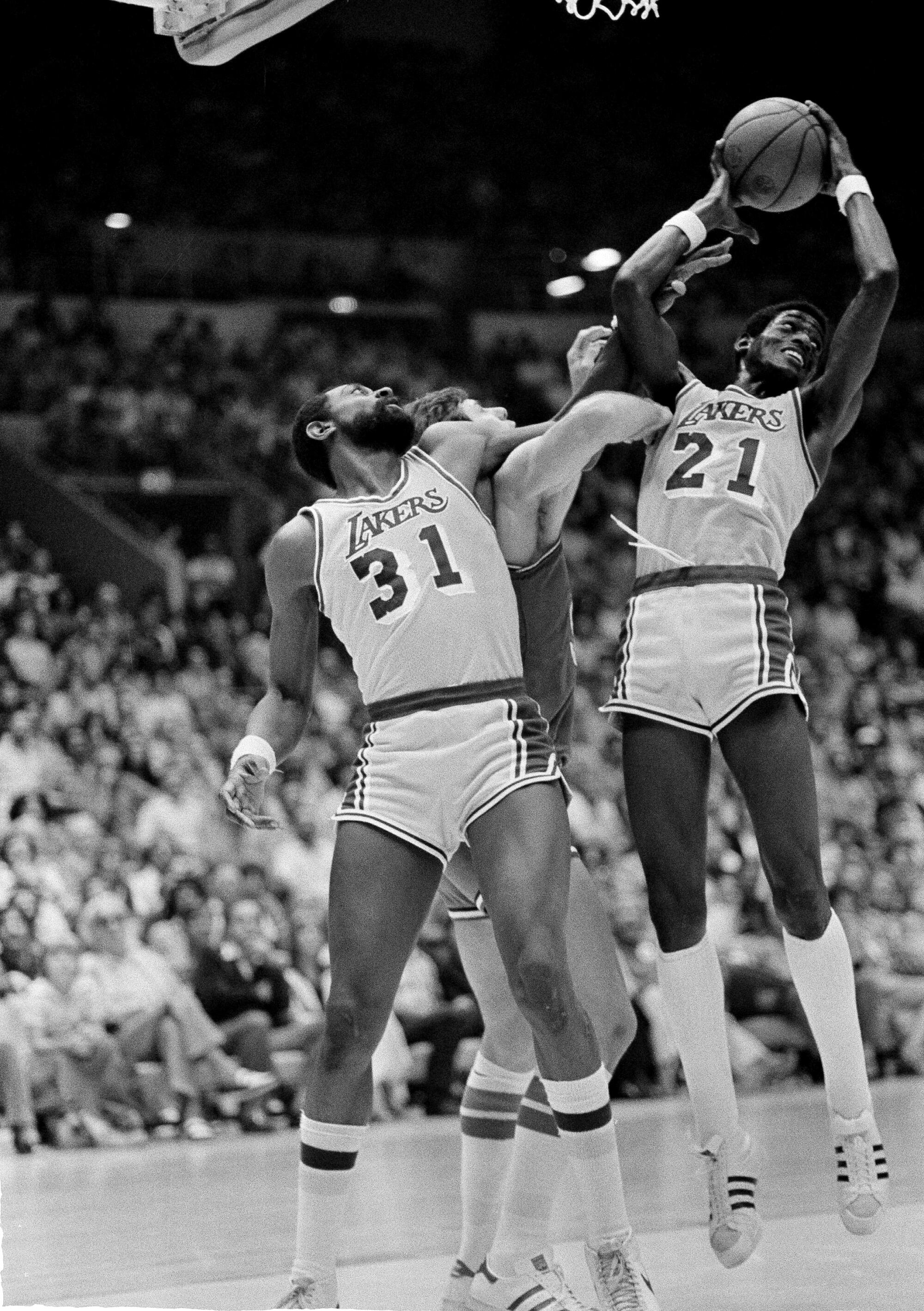

Maddox: Spencer Haywood was a really talented big guy, meaning he was a, you know, a center or power forward. He’s about 6-foot-8 and I think was having a pretty solid career up until that point. And he’d gotten in trouble here and there, but would have been a championship piece on any NBA team at the time.

Brennan: My knowledge of what Haywood was contributing on court is much less than my knowledge of what his impact was off the court. Do you remember in the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar episode, we get a little bit of a snippet of Haywood’s biggest broader impact on the NBA?

Maddox: Yeah, Spencer Haywood’s fight off the court was with the NBA, and it was in the ’70s, and, it had to do with his right to be able to play in the NBA out of high school.

Brennan: Right. The NBA at the time that Haywood was starting out in his career had a rule that stated that a player had to be four years removed from high school to join the NBA. And it ends up creating the possibility for players to be drafted straight out of high school. Who are some big players who’ve benefited from Spencer Haywood’s activism in the time since?

Maddox: Kobe Bryant, came right out of high school. Kevin Garnett … a ton of guys have come right out of high school and played in the NBA.

Brennan: One key piece of context here is that Haywood grew up poor in rural Mississippi. So his argument was that this was an economic issue in order to earn an income for himself and his family, he needed to move beyond college-level play.

Maddox: So this is someone who desperately needs and has the ability to earn a living by playing basketball. And he challenged the rule that was not allowing him to do that. But where did the drugs come into the picture?

Brennan: So Haywood discovered cocaine in the late 1970s while he was playing with the New York Knicks. And when he was traded to the Lakers, he hoped to turn around that cocaine use — until a friend introduced him to freebasing. Jeff Pearlman cited Haywood as a prime example of a player whose drug abuse ended up swamping his talents.

Pearlman: Spencer Haywood is the ultimate cautionary tale where the guy was a terrific talent who just couldn’t stop using coke. And they had money; they had disposable incomes that they could afford it. Coke was the drug of parties back at the time. These guys all liked to party. People knew; they took advantage of athletes. If you’re a dealer you would try to get athletes into it because you knew they had the money to pay for it. And before long it just became — it was a huge problem in the NBA.

Brennan: Abdul Malik argues that this is a byproduct to bring a lot of money and scrutiny to these young athletes without a support system to match.

Malik: The big money in the league meant more people had more money to burn. And a lot of these are like exploited young men, Black or white, many of them just don’t have the kind of background that gives you financial or emotional literacy and how to deal with that kind of unexpected fame.

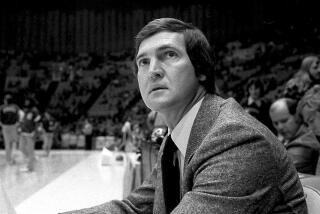

Brennan: During the course of the season, Haywood started to struggle with addiction, and his play suffered as a result. So the coach, Paul Westhead, started cutting Haywood’s minutes on court. What we haven’t gotten to in the show yet is how he would ultimately lose his spot on the team. Do you know the story?

Maddox: A little bit, but it’s not fresh.

Brennan: At the most crucial moment in the season, as victory hangs in the balance, he stays up all night smoking crack the night before practice on the eve of the NBA Finals and ends up passing out during that practice from, you know, a combination of fatigue and the comedown. He’s suspended halfway through the series and then subsequently kicked off the team.

Maddox: You feel horrible for him. You just imagine him waking up from that nap and being, like, “That was the worst thing I’ve ever done.”

Brennan: I think Spencer Haywood’s story is also a really potent illustration of the power of addiction. Haywood ultimately needed a fix so badly, because of this disease that he suffered from, that he sabotaged what would have been one of the most triumphant moments of his career. I don’t think we can finish his story, though, without talking about the sort of extreme spiral he went on after being removed from the team.

What do you know about the plan he hatched to kill Paul Westhead?

Maddox: Yeah. So I think Haywood called up some of his boys from back home and explained to them that he was upset with Coach Westhead, and they were going to figure out a plan to deal with that.

Brennan: I mean, the plan was to run Paul Westhead’s car off a cliff.

Maddox: Uh, yeah, yeah. That, yeah, it sounds like a plan.

Brennan: It got as far as being scheduled, like, they had a timeline for this. And the way it was interrupted was Haywood’s mother recognized something in his voice and said to him, “You’re up to something no good.” She even threatened to turn him in herself.

Maddox: Big save from Mom.

Brennan: I mean, you know, how moms are. She was like, “Oh gosh, my son is about to do something really f—ing stupid.” But I do want to say, that’s a really dark note and Spencer Haywood’s story is troubling in a lot of ways, but I do think it’s helpful in some important ways too. Haywood has now been sober for more than 30 years. He’s a public speaker who talks about addiction and sobriety. And he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2015. So his legacy, I think, is as someone who went into recovery after being at a really serious rock bottom and ended up finding a second act, not as a basketball player but as someone who had looked addiction in the face and managed to survive it.

Maddox: What we’re finding is that a lot of these Showtime-era Lakers, their impact is actually in something outside of basketball. And with regards to — which we’re going to talk about later — Magic Johnson and what he did for HIV/AIDS awareness, Abdul-Jabbar and his civil rights activism, Spencer Haywood, and, you know, the second act as inspiring to people suffering from addiction.

::

Brennan: Welcome back to “Binge Sesh.” So when I spoke to “Winning Time” writer and executive producer Rodney Barnes, he told me that the show’s depiction of Spencer Haywood is an attempt to correct a harmful stereotype.

Rodney Barnes: I am unfortunately old enough to remember a lot of television shows and movies about the game of basketball and sports in general, where you had a lot of Black athletes who just seem to get high for fun. And I’m of the belief that any addiction is really about pushing down some form of trauma. There’s something going on in the heart and mind of the individual.

Brennan: So my question was: How do you handle a character like Spencer Haywood, who really was an addict and really did harm his career because of it, without playing into that stereotype? Let “Winning Time” director Salli Richardson-Whitfield explain.

Salli Richardson-Whitfield: It’s like, how do we do this? We showed the reality of what it is. But then it’s our responsibility to add: What are those nuances? What are the layers? What are the reasons that he became addicted? What are those demons that people have in particular in the Black community that sucks you down that hole?

Brennan: Can you, if you can remember it, Kareem, can you describe how “Winning Time” Episode 8 actually handles Haywood’s drug use?

Maddox: No. I’m blanking.

Brennan: So I’m going to set the scene for you. It’s set during the All-Star break. So Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Magic Johnson are at the All-Star game in a different city. The Lakers who are back home in L.A. get together at Spencer’s house to watch the game — players and coaches.

And this is the episode where we see Haywood’s character use for the first time. We’ve already learned in an earlier episode about his fight against the NBA at the Supreme Court. Now we learn a little bit about his background growing up in deep poverty and coming from a family where addiction had been prevalent. And we now know that there’s a genetic component to addiction. Then we see the Jack McKinney character, who’s trying to get back into the coaching mix after his accident, sort of stir some s— by telling Spencer he’s in danger of being traded.

[Clip from “Winning Time”: Spencer Haywood character: Now, I ain’t complaining, coach. You — you’re looking at a humble man. I just — I’ll do anything to win. I want my little girl inheriting a ring.

Jack McKinney character: In that case, I’m going to need more out of you. Talking scoring, minutes; come playoffs, I want you to be prepared to carry more of the offensive load.

Haywood character: I’m surprised to hear that because the professor and Riley has got me thinking defense first.

McKinney character: I’m coming back now and they know the new deal. We’re going to get you ramped up. And I don’t want you worried about these rumors, either.

Haywood character: Rumors?]

Brennan: We also get a key scene, which I think is so important given the conversation that we’ve had about the war on drugs in the culture and in the NBA, where Haywood lashes out at the Pat Riley character by bringing up bigger racial dynamics that are at play.

[Clip from “Winning Time”: Pat Riley character: What are you talking about?

Haywood character: And here I am thinking you’ve been awful worried about me healing up. Now I know you don’t give a f— about me. Just checking my teeth for the auction block.

Riley character: Hold on a second. That’s not what happened. What — where’d you hear this?

Haywood character: What the f—’s it matter if it’s true. Huh? What f—ing, how does it f—ing matter?]

Brennan: Now that I’ve taken you through how the episode handles this and what the thought process was among the creatives, what are your thoughts on this approach? What do you think they’re trying to accomplish? And do they succeed?

Maddox: I loved the show’s treatment of this. And I think I’ve said before: I was confused by Wood Harris as Spencer Haywood at first, right? Like, what, Harris? I just don’t see him as a basketball player even though I love him as an actor. So I wondered why he was playing Spencer Haywood of all people; Spencer Haywood is not one of the people you think of when it comes to the Showtime Lakers. You think of Abdul-Jabbar, Magic, Buss, Riley, whatever, all that other stuff that we’ve been talking about for all season.

You know, finding, No. 1, an actor and casting this in a way that is going to do it justice, and spend a good chunk of time with someone who doesn’t even win that first ring with the Lakers and then doesn’t go on to continue with the team after, you know, the 1979-80 season — I think it’s brilliant and I’m glad they did that. And I think that’s why the show has some staying power and is really tackling the ’80s in a more holistic way, truly through the lens of these basketball players.

Brennan: I agree. I do think that what we see on screen shows the success that folks like Rodney Barnes and Salli Richardson-Whitfield had in rooting Haywood’s story within his individual humanity rather than treating him as a representation of a quote unquote broader problem, which as we’ve established in this episode is a suspect assumption at best.

As you pointed out, I think this is just one example of the way that “Winning Time” is using the Showtime Lakers as a prism through which to examine the entire period that we’re talking about. Next week is another story of how, if you look closely at the Showtime Lakers, in this case Magic’s HIV diagnosis, you can start to see more clearly one of the major sociopolitical happenings of the 1980s and 1990s: the AIDS crisis.

::

Brennan: … continued to ramp up during the Reagan administration, after a brief move toward decriminalization under Jimmy Carter.

Maddox: OK, Jimmy Carter?

Brennan: So yeah, Jimmy Carter, back to Jimmy. See, now you, now you understand why I have a soft spot for Jimmy? Like, he’s like a diamond in the rough here.

Maddox: Most underrated president ever. Jimmy Carter.

Brennan: Please join me for my next podcast: an appreciation of Jimmy Carter in 10 parts.

Everything you need to know about the true story of the Showtime Lakers, all in one place.

Additional resources

David Farber, ed., “The War on Drugs: A History” (2021)

Abdul Malik, “The NBA’s Drug Testing Must End,” Jacobin (Aug. 25, 2021)

Marc J. Spears and Gary Washburn, “The Spencer Haywood Rule: Battles, Basketball, and the Making of an American Iconoclast” (2020)

Jeff Pearlman, “Showtime: Magic, Kareem, Riley, and the Los Angeles Lakers Dynasty of the 1980s” (2013)

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.