Maurice Hines Jr., who went from tap-dancing brother act to Broadway trailblazer, dies at 80

The scene from the movie “Cotton Club” was fictional but encapsulated much in the relationship between Maurice and Gregory Hines. In the film, the estranged brothers, once a top-billed dance duo, come face to face in a nightclub, their wounds and vanities visible; then they reunite in a seamless virtuoso dance, followed by an embrace.

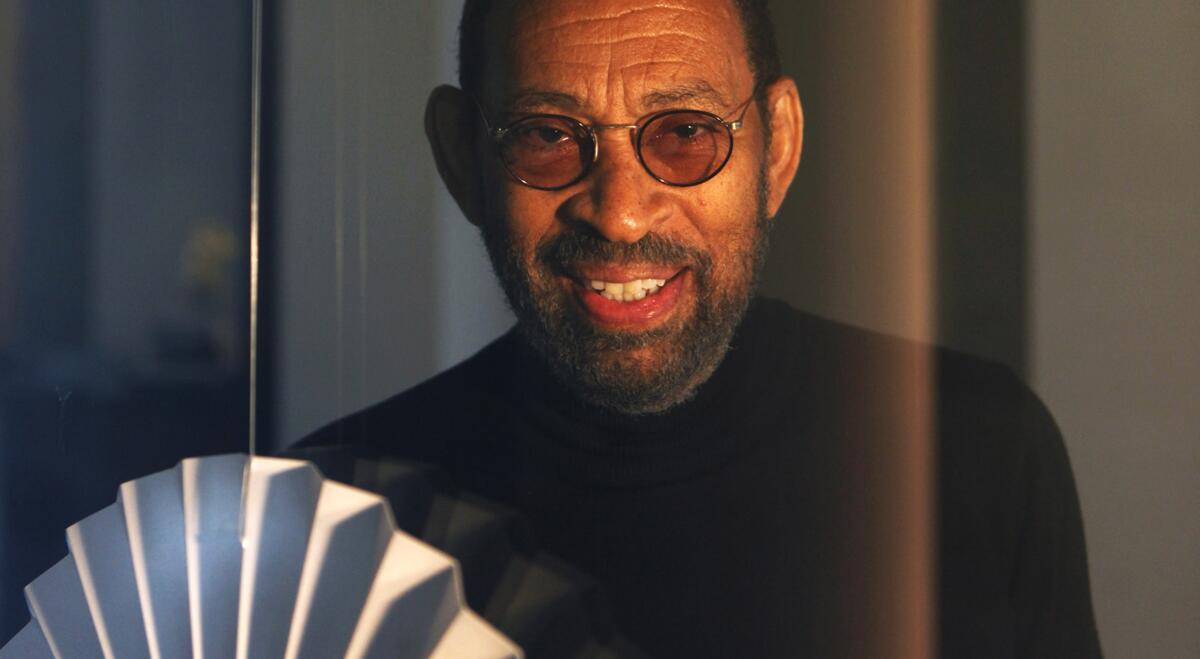

Maurice Hines Jr., the older and longer-lived brother of a famous tandem act that evolved to separate solo stardom for each man, died Friday in Englewood, N.J., said his cousin Richard Nurse, who maintains the Maurice Hines website.

Hines forged a trailblazing 70-year career creating, choreographing, directing and starring in Broadway shows — and also performing all over the world — all the while overcoming prejudice against Black entertainers in leadership roles, and also prejudice against out gay men and out gay Black men.

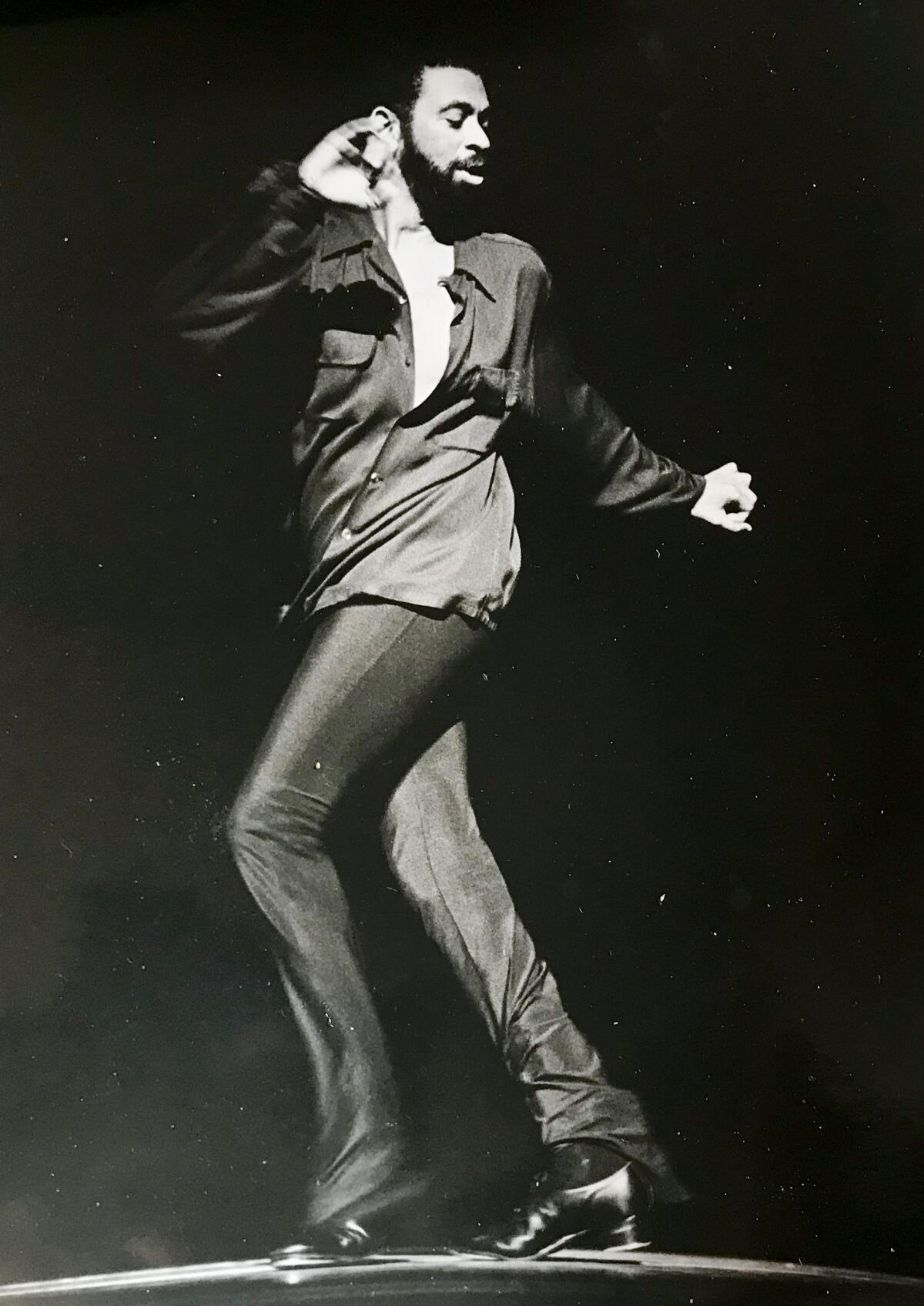

Centrally, he could flat-out dance, with tap dancing as his trademark form but not his only one.

That movie scene and another from the film exhibit those skills as well as the troubled relationship with brother Gregory Hines, who achieved surpassing fame in Hollywood. Director Francis Ford Coppola allowed the brothers to improvise their filmed interactions.

“Francis picked up on the tension and brought that into the story,” said John Carluccio, who directed and produced the 2019 documentary “Maurice Hines: Bring Them Back.” “They played it very well because clearly that was going on.”

Back in another era, when Harlem night life was famous for high style, hot music and classy dancing, the community was a magnet for uptown entertainers and downtown cafe society.

Soon after the filming, there began a 10-year period where the brothers did not speak. They put aside their differences to be with their dying mother in the latter 1990s. This reconciliation lasted until 2003, when Gregory died of cancer at 57.

Those “Cotton Club” scenes were the last they danced together.

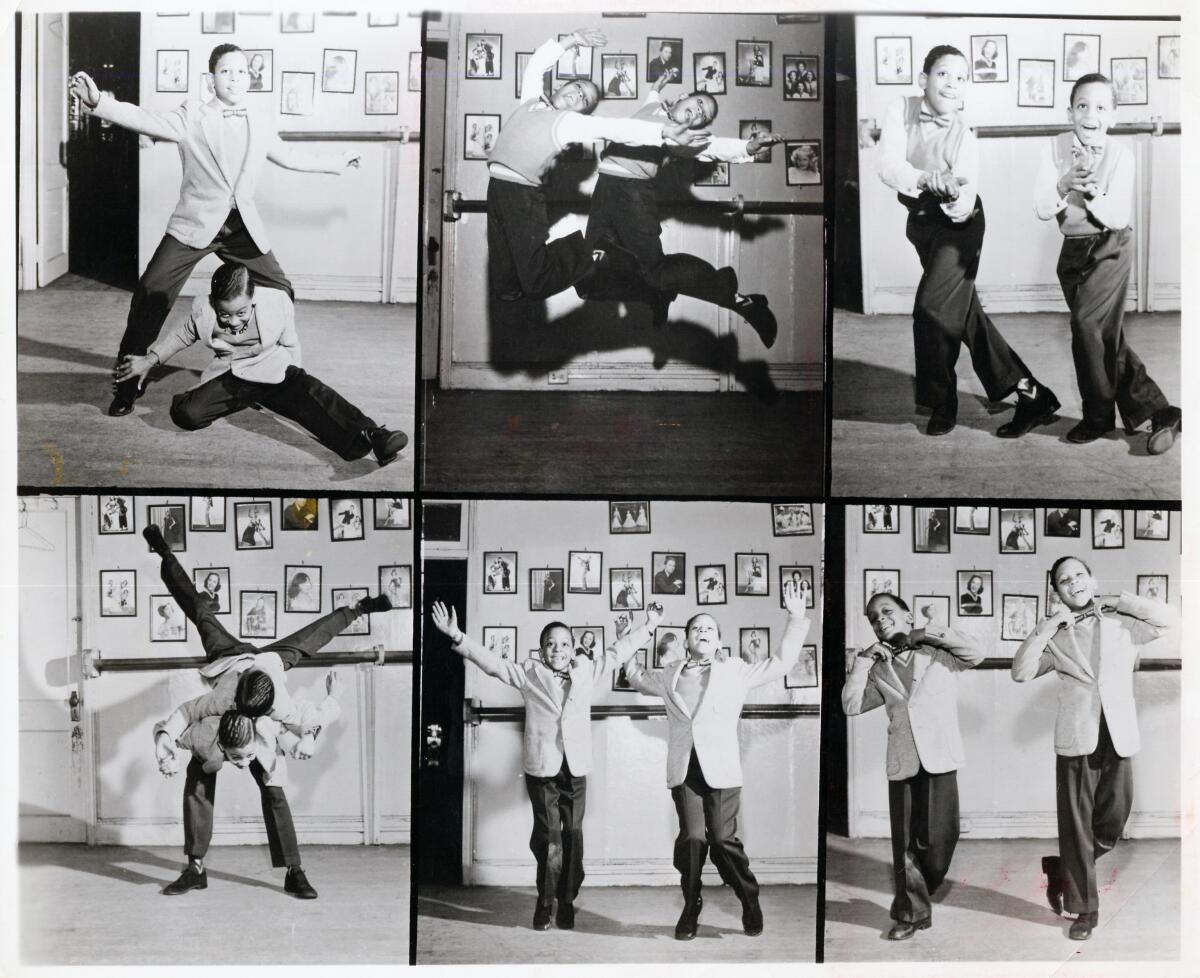

Maurice and Gregory Hines achieved early fame as perhaps the last of the great tap-dancing duos to emerge from the classic age of tap. They dazzled audiences in the early 1950s, first appearing on Broadway when they were 10 and 8 in the 1954 show “The Girl in Pink Tights.”

They also sang and, in the early 1960s, joined forces with their father, Maurice Hines Sr., who played drums as part of Hines, Hines and Dad.

Tap had fallen out of vogue, but the brothers worked steadily, appearing more than two dozen times on “The Tonight Show” alone. Gregory, however, tired of being the impish, irresistible younger sibling and decamped alone for Southern California in 1972.

Early on, as the brothers lived on opposite coasts, Maurice was faring better. He was hand-picked to star in the Broadway musical revue “Eubie!” and urged producers to give his brother an audition, while also haranguing his brother to get to New York. Gregory did not impress — his failed audition was later captured in spirit by a scene in the 1999 movie “Tap,” which starred Gregory Hines. In real life, Maurice insisted he would bow out of “Eubie!” unless Gregory was given a chance.

The 1979 show was a smash — as was their duet — but critics in particular fell in love with Gregory, and thus was launched his Tony-winning Broadway career.

Maurice would later replace Gregory — at the latter’s recommendation — as the lead in the stage hits “Sophisticated Ladies” and “Jelly’s Last Jam,” each making the role his own.

Gregory returned to Hollywood to pursue a notable film career. Maurice focused almost entirely on live theater.

“They both found their own lane,” documentarian Carluccio said.

Maurice’s energy, creativity, forcefulness and forthrightness helped him break ground creating, directing, choreographing and starring in two Broadway shows: “Uptown … It’s Hot!” in 1986 and “Hot Feet” in 2006. The latter retold Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale “The Red Shoes” through the music of Earth Wind & Fire.

Tom Smothers, one-half of the iconic comedy duo the Smothers Brothers, has died at age 86 after battling cancer. He was the older brother of Dick Smothers.

“His choreography was some of the best I’ve ever seen, breathtaking,” said veteran actor-director-producer Mel Johnson Jr., who worked with Maurice Hines on several shows. “The performers were exhausted but they loved it, because they didn’t get the chance to do that kind of dancing on Broadway.”

Despite appreciation for the dancing, neither show proved a commercial or critical success — and Maurice Hines was to do much of his best work off Broadway and on tour.

His body of theater work included tributes to other artists such as Ella Fitzgerald, the fusion of hip-hop with traditional theater, a dance company that melded tap and ballet and, late in his career, the biographical, well-received “Tappin’ Thru Life,” which featured an all-female orchestra. He also recorded albums and headlined an acclaimed, long-running nightclub act.

McCann, 88, died in a Los Angeles-area hospital Friday after being hospitalized with pneumonia, his longtime manager and producer told The Times.

Maurice Robert Hines Jr. was born in Harlem in New York City on Dec. 13, 1943. Gregory was born Feb. 14, 1946. Their mother, Alma Lola Lawless Hines, became a canny manager of the family act. Maurice Sr. was both jack-of-all-trades and working-class Renaissance man, for a time alternating roles as nightclub bouncer and drum-playing orchestra leader, Nurse said. After serving as a mariner in World War II with the Merchant Marine, he sold soda and played professional baseball in Canada. Late in life he became a chef.

Maurice started dance lessons at 5 after fledgling dance studio owner Henry LeTang went door-to-door recruiting for students, Nurse said. Maurice would immediately teach what he learned to 3-year-old Gregory.

LeTang, who later became a force on Broadway, spotted the boys’ talent and drive — and soon began private lessons.

The boys began performing, including at Harlem’s legendary Apollo Theater, where bad acts were not tolerated.

And they watched, performed with or learned directly from such talents as the acrobatic Nicholas Brothers, jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald and entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. — incorporating elements of those performers’ artistry into their own work.

“We wanted to see all the great tap dancers,” Hines told documentarians. “We saw Coles and Atkins and we saw Bunny Briggs and Teddy Hale, Baby Lawrence. We were learning from these guys and we wanted to be up close so we could see their feet. ... The quality that they all had, that I wanted so badly — and I do have it but I learned from them — was ... appealing to the audience, be one with the audience, being honest and real with them.”

The boys quickly became popular across the country, opening for entertainers such as Lionel Hampton and Gypsy Rose Lee. They started off as the Hines Kids, became the Hines Brothers and finally Hines, Hines and Dad — until Gregory broke up the act.

Although the split hurt Maurice emotionally, each brother grew artistically. Maurice studied ballet, African and Dunham Technique as well as studying with modern maestro Alvin Ailey and jazz dance innovator Frank Hatchett. His body became limber and stronger, his turns sharp and fast.

He had to “redesign my body,” as he put it. “It was hard.”

Gregory, in turn, developed an earthy, explosive, emotive improvisational style that built on Black rhythmic traditions and influenced an entire generation that followed, including current star Savion Glover, whom Gregory mentored.

Both brothers became key figures in the revival of tap dancing through their teaching, performing and personal connection to greats of the past.

“My brother and I tap completely differently although we were both taught by Henry LeTang,” Maurice Hines told The Times in 1994. “We have very different stances. My style tries to be exactly like Fayard Nicholas, a full body style. [Gregory] dances from the waist down.”

It was ultimately Gregory Hines who became the defining tapper of his generation, although both brothers were undisputed masters of the craft.

Maurice Hines headlined shows into his early 70s, finally slowing down as health problems and accelerating memory issues took their toll, family and friends said.

Hines is survived by an adopted daughter, Cheryl Davis, whom he raised with former longtime companion Silas Davis. Funeral plans are pending.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.