Norman Pfeiffer, prolific architect of SoCal institutions and L.A. Central Library expansion, dies at 82

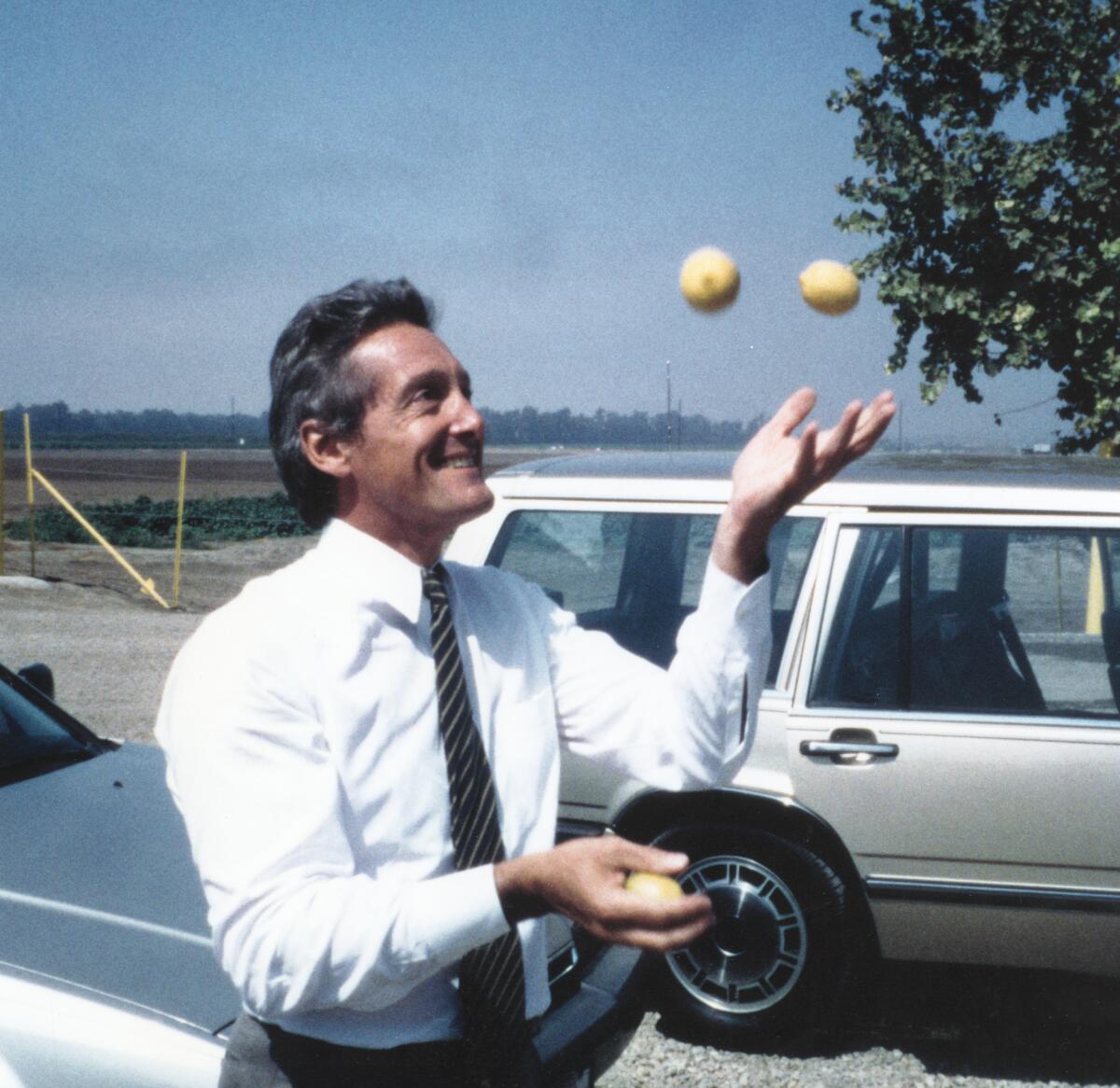

Norman Pfeiffer, an architect with a more than half-century-long devotion to projects in the L.A. public realm, died Aug. 23 at his home in Pacific Palisades. He was 82.

“Norman is perhaps the architect with the greatest impact on Los Angeles’s cultural sector,” said his wife, Patricia Zohn, in reference to his contributions to venues including Griffith Observatory, Los Angeles Central Library, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, among others. “Yet he was also the antithesis of a starchitect: modest, self-effacing and with a focus squarely on the project.”

Through his firms Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer and Pfeiffer Partners, he approached architecture as a relational practice. Born in 1940 in Seattle, Pfeiffer was inspired as a young man by his grandfather, a master woodworker, and the fact that his parents’ homes were both hand-built by family members. Brimming with energy, Pfeiffer divided his time between his two lifelong passions, architecture and baseball, throughout early adulthood. While obtaining a bachelor of architecture degree at the University of Washington, he played shortstop and second base for the school’s team as well as a traveling team known as the Cheney Studs. “He used to carry his drawing board on the team bus to keep up with his architecture assignments,” Zohn recounts.

Shortly after graduating from Columbia University with a master of architecture degree in 1965, Pfeiffer joined architects Hugh Hardy and Malcolm Holzman to establish Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates (HHPA) in New York. Through directing the design and construction of several cultural, civic and commercial projects for the firm, Pfeiffer fostered his passion for human-scaled architecture in an increasingly automobile-scaled nation.

The Columbus Occupational Health Center, completed in 1973 in Columbus, Indiana — a city bearing architectural gems from the likes of Eero Saarinen, Robert Venturi and I.M. Pei — became one of Pfeiffer’s first major projects that unambiguously put people first. When it was selected for a national AIA Honor Award in 1976, the jury applauded the clear organization of its many facilities, “which relieves the tedium of clinical work and the anxiety of patients,” as well as its vibrantly hued mechanical and structural systems designed to further elucidate the building’s many components. Through this and other works, HHPA received the 1978 AIA New York Chapter’s Medal of Honor, and Pfeiffer was elected to the AIA College of Fellows in 1981, the youngest member ever given the honor at the time.

In 1986, Pfeiffer moved to Los Angeles and opened a second HHPA office to oversee the completion of the Robert O. Anderson Building, the street-facing addition to the original Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) campus. Its unmistakably 1980s glass brick facade served as a towering buffer between Wilshire Boulevard and the Times Mirror Central Court at LACMA’s center, where “slender green glazed piers soar four stories to a ceiling of saw-toothed, factory-style translucent skylights,” as William Wilson described for the Times in 1986.

Though Wilson and other critics believed the addition successfully wove the campus together following two decades of incoherence, it too unceremoniously met the ax in 2020 to make way for Peter Zumthor’s controversial, forthcoming David Geffen Galleries. “The denouement of the LACMA building was hotly contested at the time,” Zohn recalls, “but Norman — typically — did not engage with it.”

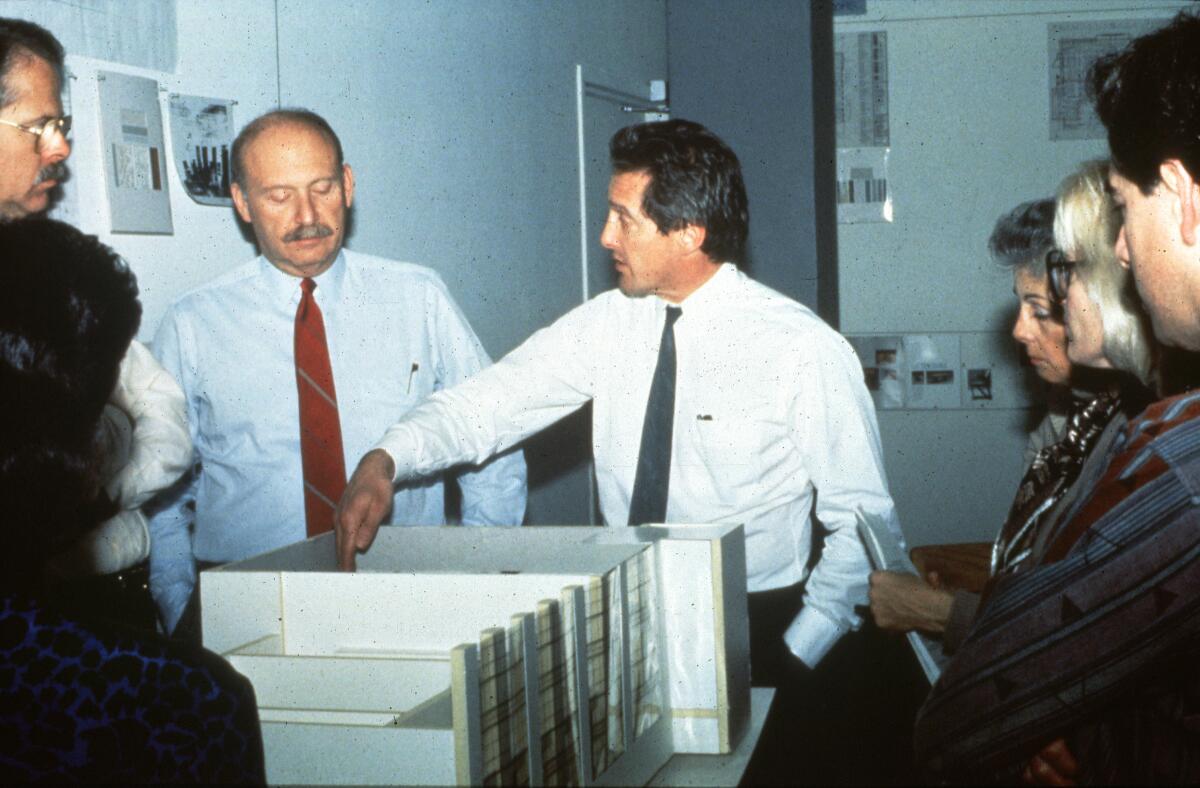

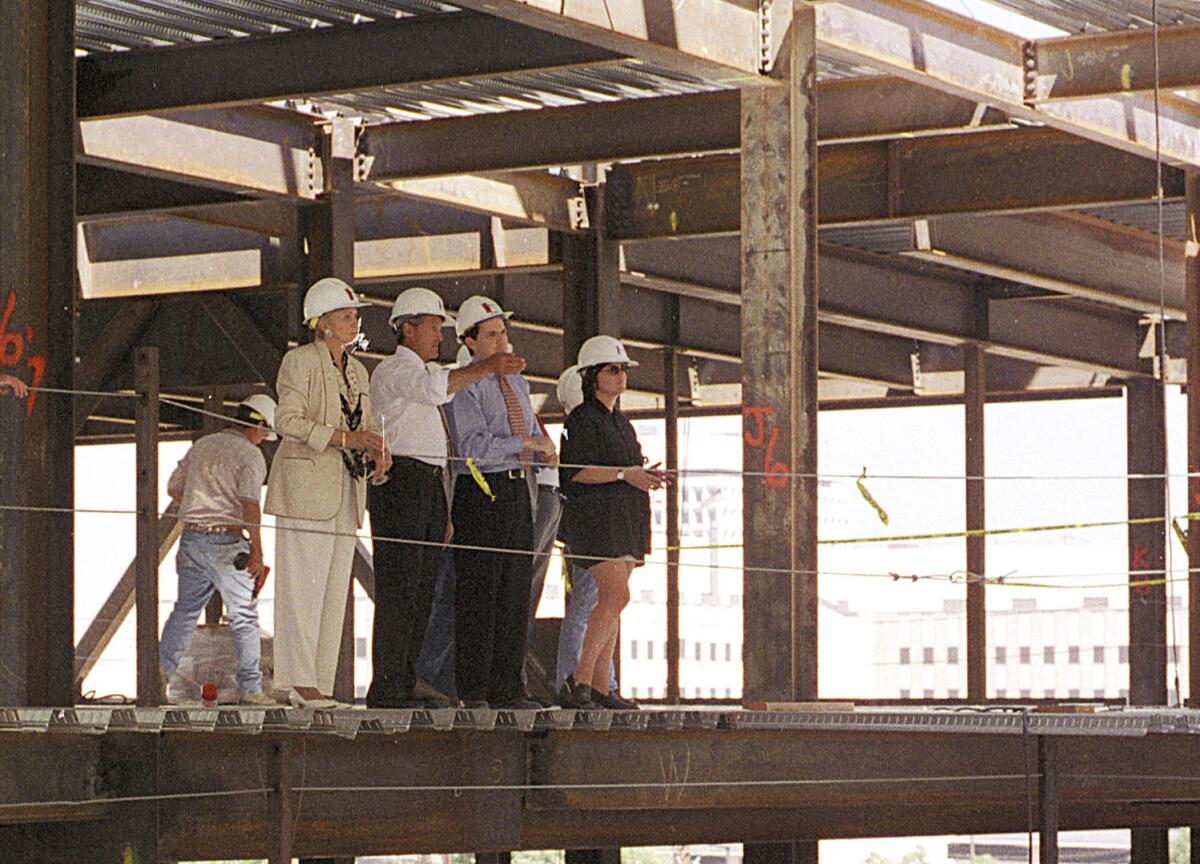

The renovation and expansion of Bertram Goodhue’s 1926 Los Angeles Central Library, completed in 1993, became one of Pfeiffer’s proudest personal accomplishments. His enthusiasm for working with the historic structure is detailed in “The Library Book,” Susan Orlean’s bestselling account outlining the fire in 1986 that nearly brought the library to ashes. “Pfeiffer’s design centered on an eight-story atrium,” wrote Orlean. “Even though the addition was massive, it wouldn’t challenge the height of the original building, because four of its stories were belowground [...] The experience of passing through both buildings would be like walking through an eccentric playhouse and then tumbling over a waterfall.”

In far more subtle detail, Pfeiffer designed custom carpets and related upholstery throughout that borrow from patterns and images visible in the intricate ceiling design of Goodhue’s dazzling rotunda. “His masterful renovation of the Central Library revitalized downtown L.A.,” said longtime family friends Julie and Roger Corman. “It shows that Norman understood Los Angeles as a city with both a rich history and a future full of light and amusement.”

Betty Teoman, the former director of Los Angeles Central Library, remembers Pfeiffer’s demeanor as he first presented his proposal. “In public meetings where people were often passionate and emotional about their positions, Norman was the island of calm,” Teoman said. “His steady hand on the public and behind-the-scenes design process was key to the project’s success.”

Pfeiffer applied this same level of deference to his design for the Colburn School, completed in 1998 in downtown Los Angeles. “Of all the architects the Colburn School considered to design the Grand Avenue building,” explained Toby Mayman, an honorary life director of the Colburn School, “Norman was the only one who sent a team to the school’s existing site [a former furniture warehouse on Figueroa Street] to get a real sense of the school’s real mission and its programmatic needs and hopes for the future.”

“The challenge was to design a high-quality concert hall at a scale that would allow young children to feel comfortable in the audience and on stage,” said Jean Gath, the managing principal of Pfeiffer, a Perkins Eastman Studio (as Pfeiffer Partners is now known), who worked on the project with Pfeiffer. The brick and zinc exterior facing Grand Avenue belies a spacious yet intimate concert hall at its center, around which orbit several smaller recital halls and dance studios. A few years later, Pfeiffer designed an adjacent student housing tower and adjoined the two facilities with a courtyard and dining commons envisioned as an open-air campus amid skyscrapers.

Following the dissolution of HHPA in 2004, Pfeiffer became one of the go-to designers for education spaces — particularly in California, with clients including Stanford, USC, Cal State Long Beach, Caltech and UCLA. At UC Santa Barbara, Marc Fisher, the former vice chancellor for administrative services, said, “Norman and his team brought new life to the center of campus by transforming the tired university library through brilliant addition, reduction and renovation. On opening day, the students flooded the building and proclaimed it their own.”

Pfeiffer’s newfound independence from HHPA also allowed him to take on more historic preservation projects, most notably the renovation and expansion of the Griffith Observatory, completed in 2006. Incorporating several new facilities while maintaining the building’s iconic outward presence — essentially a magic trick — required the painstaking re-creation of the sprawling front lawn to its original specifications to install a 40,000-square-foot exhibition space beneath its sea of green.

“As an architect, Norman was able to think beyond the edges of a building to consider what a building can do for a community,” Gath said. “As a leader, his legacy is one of collaboration. The six new partners of the firm he started work well together, thanks to his role as a mentor unafraid to step aside to let the next generation lead.”

In addition to Zohn, Pfeiffer is survived by two children from his first marriage, Alexander and Medby Pfeiffer, two children from his marriage with Zohn, Nicholas and Patrick Pfeiffer, as well as four grandchildren.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.