Rare photos of David Bowie’s train travels through 1970s-era Soviet Union are now on view

There’s no shortage of flashy, high-octane David Bowie photographs out there depicting the rock icon’s many transformations, from ’60s mod to ’70s glam rock to ’80s suit-slick to his sparkly, orange-hued Ziggy Stardust alter ego. An exhibition at Culver City’s Wende Museum, however, offers rare, intimate photos of Bowie on holiday — in the Cold War-era Soviet Union.

In 1973, after performing in Japan as part of his Ziggy Stardust/Aladdin Sane tour, Bowie headed home to Europe through the Soviet Union. He was fearful of flying and journeyed by boat, car and train with a close childhood friend, Geoff MacCormack, a percussionist and backup vocalist on the concert tour. The trip included a week on the Trans-Siberian Express from the city of Khabarovsk to Moscow, where they stayed for two days.

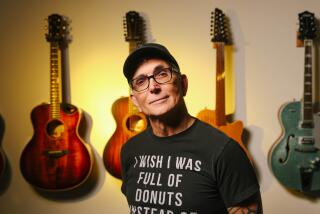

Before they embarked on their trip, Bowie bought a 16mm movie camera in Japan and MacCormack, who later made a living as a songwriter and producer in advertising for 20 years, bought a Nikkormat camera. They documented their journey on and off the train, capturing the landscapes whizzing by, their fellow travelers and each other, both posing for the camera and in candid moments. Footage from Bowie’s “The Long Way Home” film is also on view at the Wende.

“This exhibition is basically holiday snapshots,” says Olya Sova, who guest-curated the Wende exhibition. “Not David Bowie in the studio, no makeup or posing with lights. It’s just two friends traveling together and having fun and exploring places that are really different from their reality.”

MacCormack spent three years traveling with Bowie, from 1973-76, and he took photos throughout that period. He revisited his archives after Bowie died in 2016. About 150 of his photographs appear in his recently released book, “David Bowie: Rock ’n’ Roll With Me.” Many of them went on view in exhibitions in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 2018 and Brighton, England, in 2020; others have been shown at L.A.’s Morrison Hotel Gallery.

But the Wende Museum show, of the Soviet Union trip exclusively, is the first time any of MacCormack’s pictures from Russia have gone on view in the U.S. This year marks 50 years since their trip, which is why he and Sova decided to present the show in L.A., a city Bowie and MacCormack visited together.

Here’s what MacCormack had to say about the story behind some of the images in “David Bowie in the Soviet Union.”

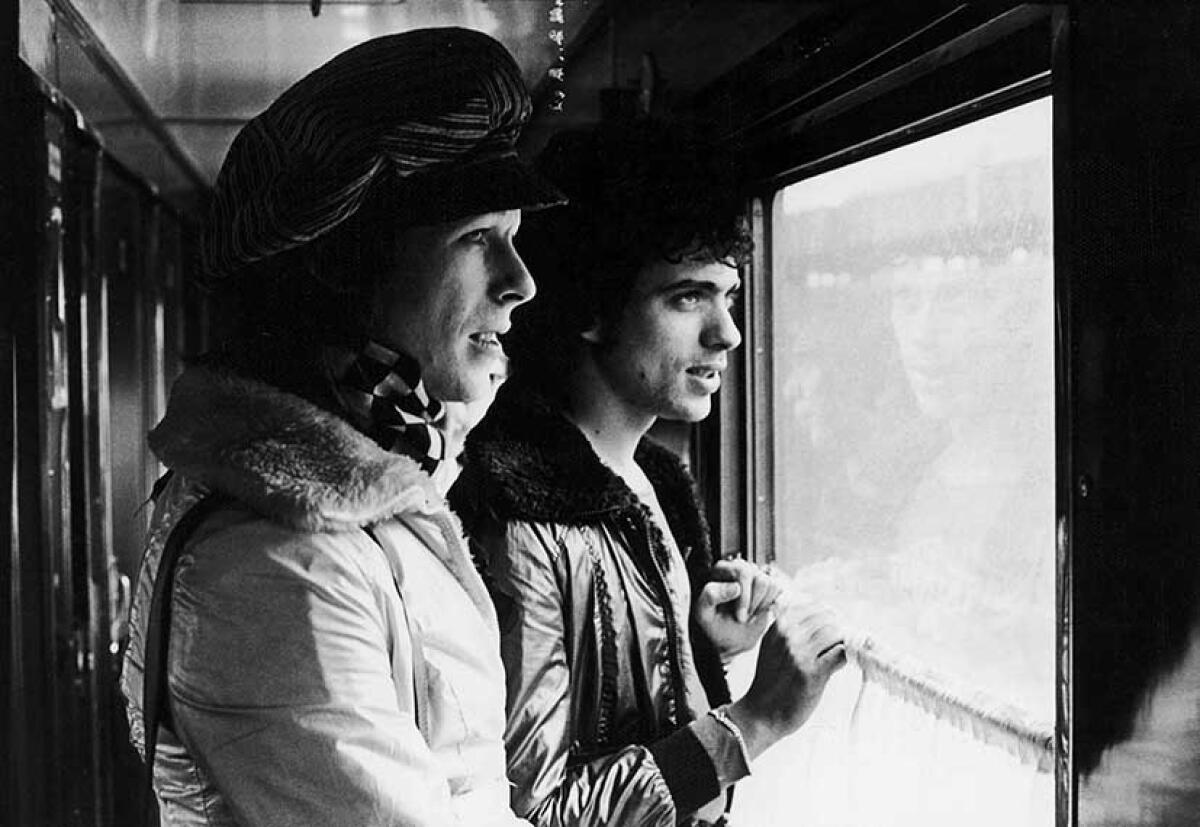

That’s early in our journey. I know because after a week, you don’t look out the window anymore. We thought how vast Siberia was. You feel like an impostor on a train because you’re not really part of what you’re looking at; you’re just a voyeur. Very strange feeling. You can’t stop the car or the train, you’re just a passenger. We were probably talking about Japan there. We would have headed for the food car right after that. Leee Black Childers, a photographer that Bowie’s management employed, took this. He traveled with us for some of the trip.

Only tourists knew who [Bowie] was, but not the Russians. He was just breaking out. He liked the anonymity. I think it gave him a respite between touring and reinventing his next album. Time to sit back and take stock.

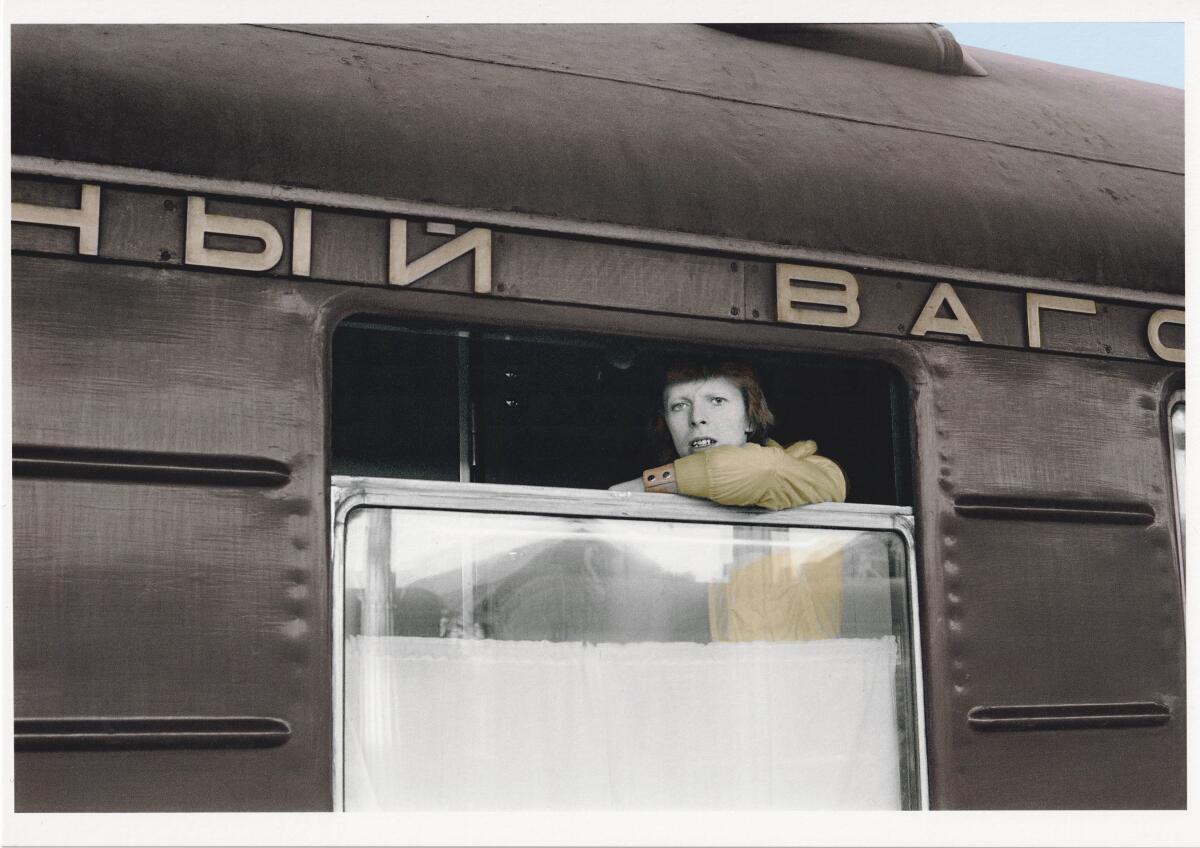

This is a train station. In the carriage, they left certain documents for us to peruse, including government policy for foreigners. The Russians already knew the rules. There was a list of restrictions: You couldn’t take any photographs of bridges, for example, or train stations. Ha. We didn’t take any notice of the instructions about not taking photographs, though. We took photographs and film of lots of stuff. Probably because we were stupid and didn’t know the real consequences of our actions. It was probably unwise, but I’m glad we did. By definition of being young Londoners, of course, we were rebels.

I didn’t know the significance of that station until later [it was a junction for prisoners headed to the country’s gulag labor camps]. I just took pictures of any action. I was merely recording our journey.

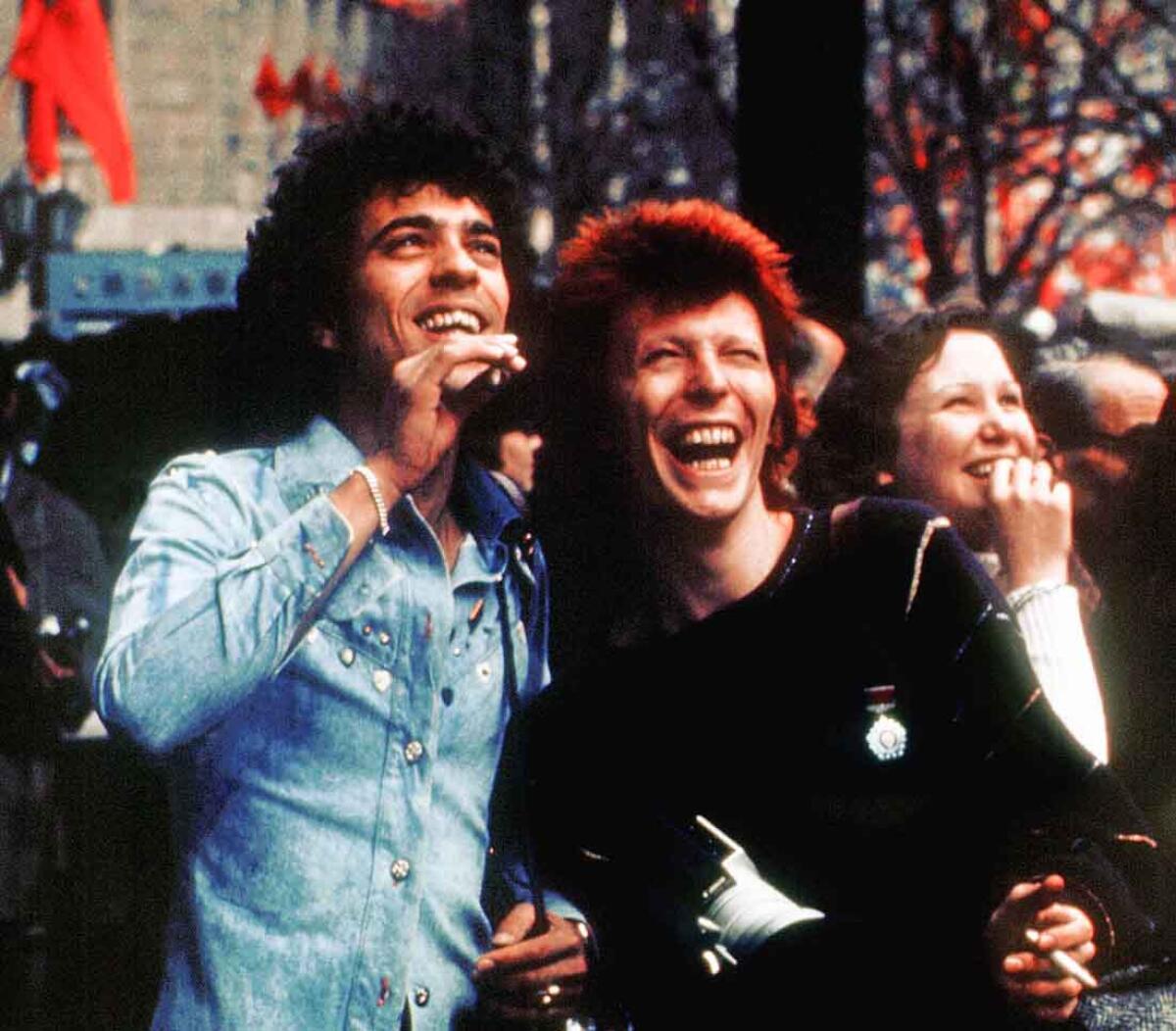

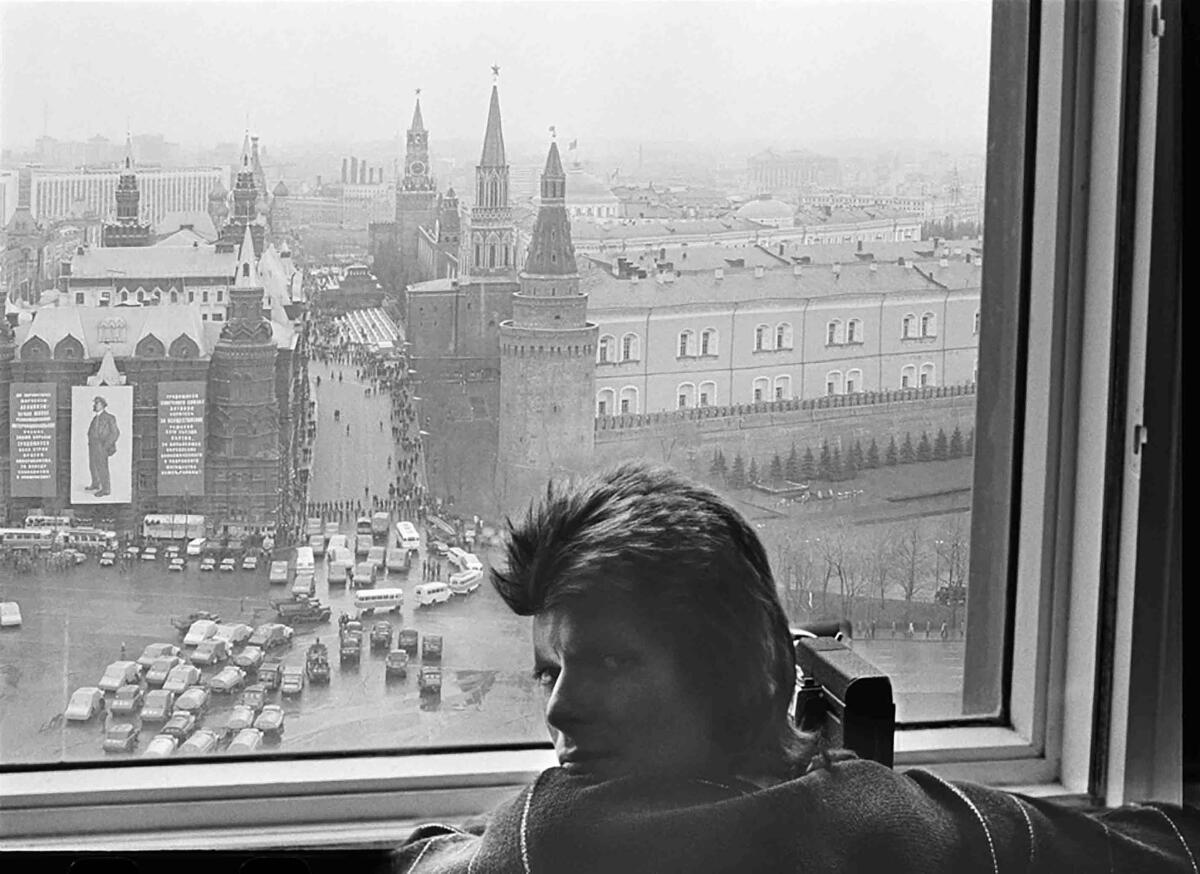

This one’s really sweet, I love this one. We were in Moscow. It was the May Day parade. I think Leee Childers took this one. I can’t imagine at all what we were laughing at, but we did a lot of laughing. Laughing was a safety [mechanism] throughout life; it relieved pressure for us.

We met some tourists from France and a few from America and some young Russian soldiers in their 20s, and we started talking to them, drinking with them — vodka and beer. And they were asking us about music and about the West, and we were telling them about stuff. Getting very drunk. The more we drank, the more we understood each other. And singing was sung.

The Russians put out a recording, which was like Muzak, on the train and one of the tapes was Russians singing Beatles songs in English. But some of the words didn’t come out right. On a track called “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” there’s a line “Desmond says to Molly, ‘Girl, I like your face.’” But they sang it: “Desmond said to Molly gal ‘I lick your fass.’” When that track went round and round, we sang it — loud — with all the Russian influencers on the train. It was a very good time.

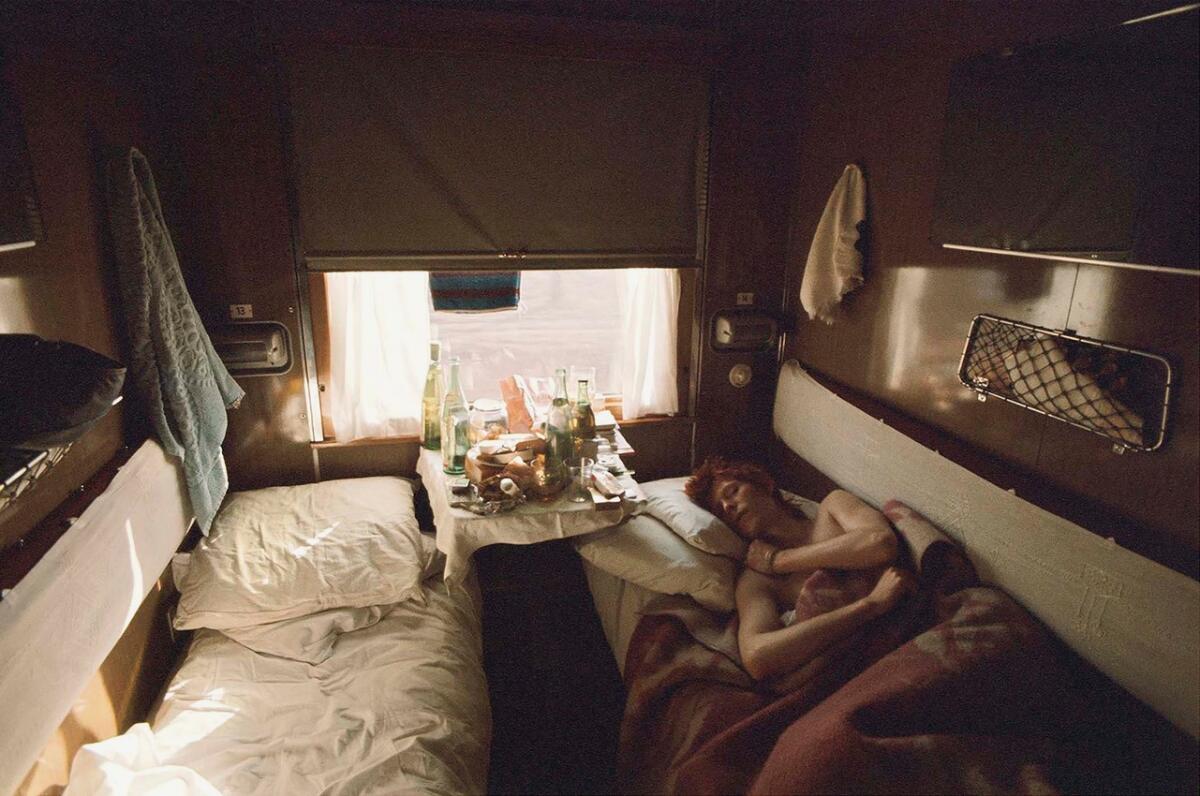

I got up before David the next morning and there is evidence of beer and cheap Romanian wine. He must have drunk more than me. But you never get hung over when you’re 26 or 27.

This was the Macy’s of Moscow. It was the place to go, the No. 1 department store. That’s how we dressed. I just love his courage — the orange pants, yellow jacket, the boots. To not try and blend in, it’s wonderful. To know yourself and not be afraid to dress how you want is quite something. People were almost disgusted by us because we were so decadent. No one really approached us except kids. They’d give us revolutionary badges with pictures of Stalin on them and we’d give them gum.

But this photograph — it just shows you how much of an individual [Bowie] was. Courageous.

We were in the hotel, an approved hotel for tourists. There was a woman at a desk in every lobby, on every floor, sitting and watching to see where everyone went. We were around the corner, filming out of the window. That’s why David looks so furtive — because he wasn’t supposed to be doing that. We were filming what, behind the scenes, the soldiers in their trucks were doing while the May Day parade was going on. We got away with it. If we had looked ordinary, we might not have, but because we looked so freaky, we got away with it. No one wanted to approach us, in case they got contaminated with rock ’n’ roll disease.

‘David Bowie in the Soviet Union’

Where: Wende Museum, 10808 Culver Blvd., Culver City

When: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Fridays through Sundays. Wednesdays and Thursdays are open for school tours only. Closed Mondays and Tuesdays. Through Oct. 22.

Cost: Free

Info: (310) 216-1600, wendemuseum.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.