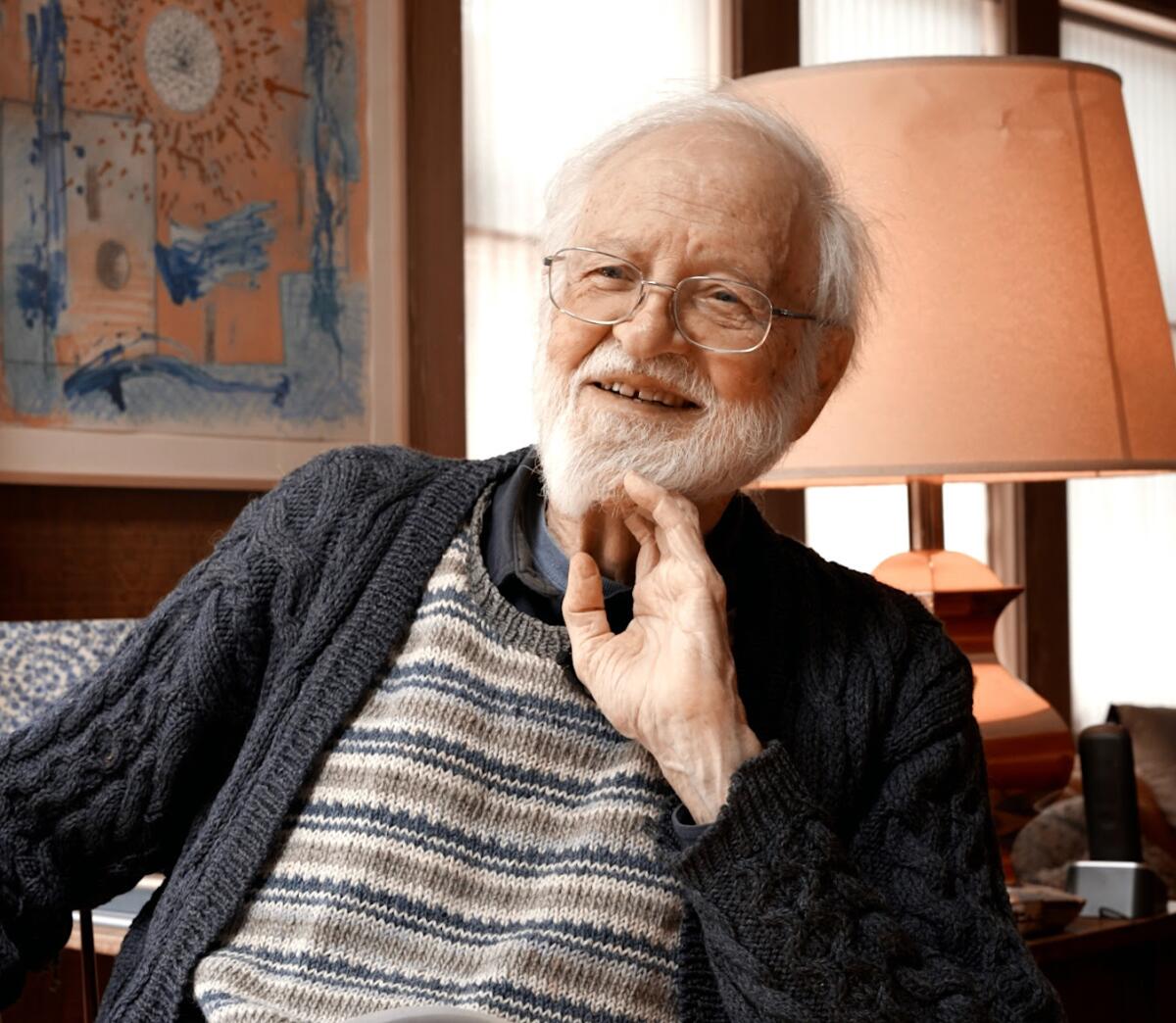

Appreciation: Beloved artist and professor Jim Melchert taught us the value of paying attention

In 1992, I took an art class in narrative forms at UC Berkeley. The instructor was Jim Melchert, then in his 60s and a central figure in the Bay Area art community. Our primary medium in the class was the photocopy. Every week, we each made an artist’s book with enough copies for each student to have one.

Near the end of the semester, Jim (we never called him “Professor Melchert”) invited our small class over to his house for dinner. Video artist Bill Viola was in town and screened one of his works. Afterward, buoyed by conviviality, a few of my classmates and I drove around all night, talking and smoking. On the day of our last class, the driver from that night presented the ashtray from his car, overflowing with cigarette butts: gross, yes, but a narrative form we made together, catalyzed by Jim.

Throughout his career, Jim remained open to serendipity. He created elegant, conceptually driven work in clay, film, photography and performance, where he embraced experimentation, play and improvisation. Unfailingly friendly, he was beloved and respected as a teacher and mentor, but his skills extended beyond the studio and the classroom. He was the first artist to serve as visual arts program director for the National Endowment for the Arts, and later served as the director of the American Academy in Rome. Jim passed away at the age of 92 on June 1 at his home in Oakland of complications from a stroke. He is survived by his three children, five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

James Frederick Melchert was born on Dec. 2, 1930, in New Bremen, Ohio. The third and youngest son of Rev. John Carl Melchert and Hulda Egli, he graduated with a degree in art history from Princeton University in 1952. Declaring himself a conscientious objector during the Korean War, he was given alternative service teaching English in Sendai, Japan, where he lived for four years. There he met and married Mary Ann Hostetler, the daughter of Mennonite missionaries. They had two sons before moving back to the United States in 1956 so he could pursue a master of fine arts in painting at the University of Chicago. Mary Ann passed away in 2005.

In Chicago, Melchert was introduced to Abstract Expressionism, the dominant American style of painting at the time, although he worked in a representational style, mostly still lifes. After graduating, he became the only art instructor at Carthage College, where he was also required to teach ceramics. To keep ahead of his students, Melchert enrolled in a summer class in Missoula, Montana, taught by Peter Voulkos, who was then radically reshaping ceramic art in an Abstract Expressionist mode. Voulkos made such an impression that in 1959 Melchert became his studio assistant, moving his young family to California, where Voulkos taught at UC Berkeley. Melchert earned a second master’s degree in ceramics there.

In the early 1960s, Melchert taught ceramics and sculpture at the San Francisco Art Institute and immersed himself in the Bay Area art scene, befriending artists such as Carlos Villa, with whom he once shared a studio, Manuel Neri, Nathan Oliveira and Joan Brown. Through Voulkos, he also made connections in the L.A. ceramics world, including John Mason, Henry Takemoto and Michael Frimkess. Melchert’s early ceramic work combined qualities of Abstract Expressionism with the eclectic, figurative impulses of the emerging California Funk movement. His sculptures from this time look like whimsical industrial castoffs or colorful yet mangled theatrical masks, toeing the line between objects and bodies, abstraction and figuration. In 1964, he joined the art faculty at UC Berkeley, where he taught until his retirement in 1994.

In the 1970s, Melchert’s work began to move in a more conceptual direction, influenced by concrete poetry and the work of composer John Cage. In 1972, he organized a performance called “Changes” at Hetty Heisman Studio in Amsterdam, in which he and a group of Dutch artists each dunked their heads in a bucket of wet clay slip and sat on a bench as the slip dried and cracked, becoming a kind of living sculpture.

In 1976, Melchert left the Bay Area for the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington, D.C., where he strengthened and diversified grant programs supporting artists and nonprofit art spaces. He returned in 1981, but three years later was tapped as director of the American Academy in Rome, where he served until 1988.

His travels around the Mediterranean led to his interest in ceramic tiles, a preoccupation that lasted for the rest of his life. He was fascinated by the myriad ways a tile cracked when broken, learning from a physicist that the resulting lines and fissures happen where molecular bonds were the weakest. He created numerous works in tandem with these cracks, creating abstract designs on broken tiles that could resemble constellations, sound waves or flowers. He continued making these works and exhibiting until very recently; the last artwork posted on his website is “Shards 2” dated 2021-22.

It was in Jim’s class that I first felt the inkling that there was more to being an artist than simply expressing yourself. It was also about paying attention — looking closely and curiously — and being open to where it might take you. In a 2020 interview with Constance Lewallen for the Brooklyn Rail, Melchert said of his broken tile works, “Like rivers will take the path of least resistance, so will the energy shooting through a tile. … It’s a wonderful thing, that you can just liberate something from a material. I loved that.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.