After four decades, ‘A Soldier’s Play’ is still urgent in Tony-winning revival

Charles Fuller’s 1981 drama “A Soldier’s Play” is a fiercely complex study of race relations neatly packaged as a whodunit. By the end, the murderer is revealed, but guilt is spread all around and justice remains an elusive quest.

The Tony Award-winning revival of this Pulitzer Prize-winning drama, directed by the ever-reliable Kenny Leon, doesn’t disappoint. This touring production, which opened on Wednesday at the Ahmanson Theatre, seizes hold of the audience with the mysterious murder of Sgt. Vernon C. Waters (played by veteran Eugene Lee), a Black noncommissioned officer who is fatally shot while stumbling home from a club one night after too much to drink.

“They still hate you,” Waters mutters repeatedly in his final moments. The scope of this “they” will be as much the subject of inquiry as the identity of the person who pulled the trigger.

Pasadena Playhouse wins the Tony Award for regional theater excellence, becoming only the second Los Angeles institution to earn the honor and continuing its triumphant streak after years of turbulence.

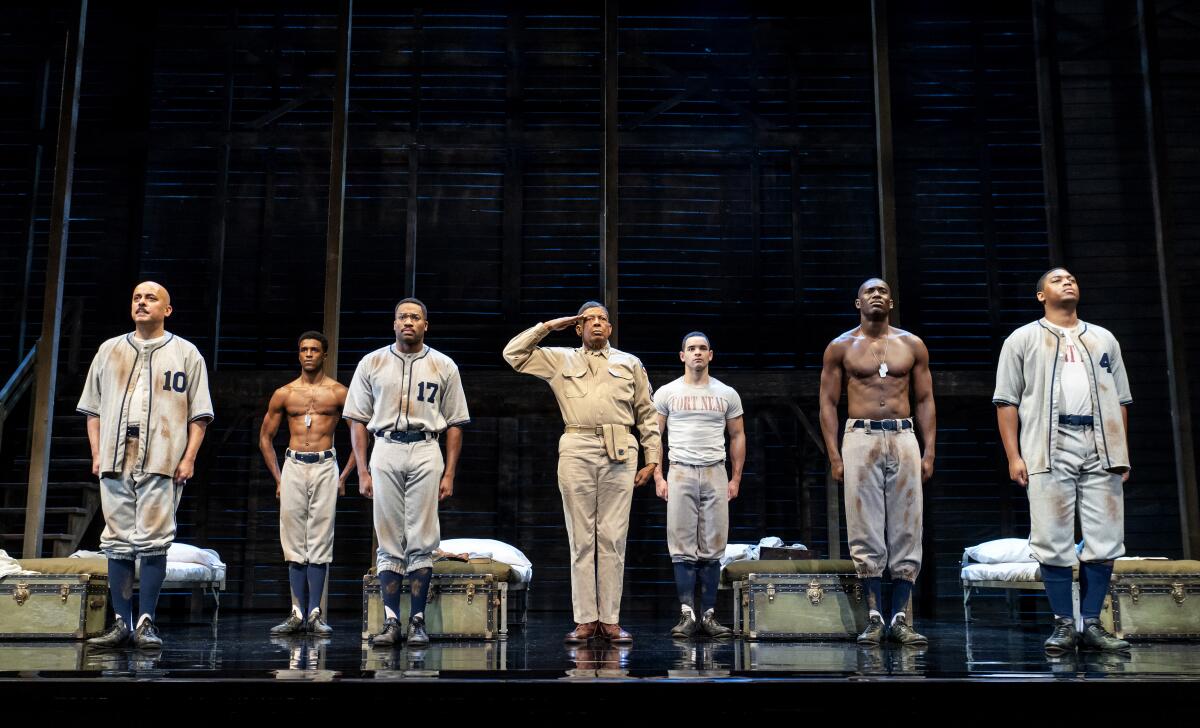

The action is set in Fort Neal, La. It’s 1944 and the military is still segregated. Racism is pervasive, and the prevailing assumption is that the Ku Klux Klan lynched Sgt. Waters.

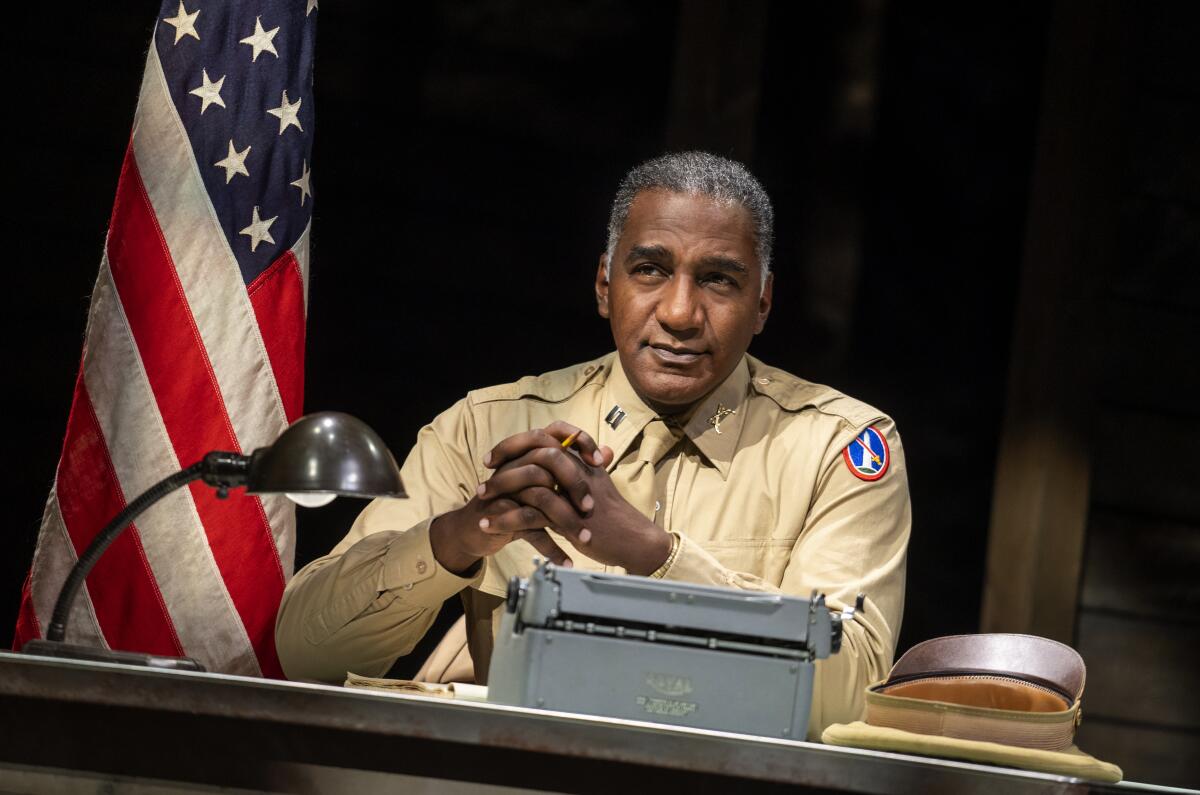

Capt. Richard Davenport (Norm Lewis), a Black officer with a law degree from Howard University, is brought in to lead the investigation. His commanding stature fills the Black soldiers with pride and the white military men with a mix of antagonism and confusion.

Capt. Charles Taylor (William Connell), a white officer, wants to get to the bottom of this murder. He too thinks the killing was racially motivated, but he doesn’t believe a Black officer will be able to apprehend and convict a white person in Louisiana. The locals simply won’t permit it.

“Captain, did you see my orders?” Davenport coolly replies. He has no intention of backing down from this assignment. Placating prejudices advances nothing. But his commitment to objectivity will raise moral dilemmas that don’t have easy answers.

Davenport discovers during his investigation the sadism of Waters, a martinet who shamed, browbeat and tormented his men. Private C.J. Memphis, a guitar-strumming gentle giant with a country bumpkin way — touchingly incarnated by Sheldon D. Brown — is the main target of Waters’ irrational ire.

“A Soldier’s Play,” which was adapted into the 1984 film “A Soldier’s Story,” was inspired by Herman Melville’s novella “Billy Budd.” Waters’ antipathy toward C.J., much like John Claggart’s hostility toward Billy Budd, has a strong element of self-hate. But here the issue is internalized racism. What the other Black soldiers adore about C.J. — his simple kindness and athletic and musical gifts — incenses Waters.

The sergeant, a fanatical assimilationist, strives to be accepted by white society by adopting its values and biases. A part of him recognizes that this is a losing game, but he puts the blame on Black men like C.J., whom he calls an “ignorant, low-class geechy.”

Martin Scorsese’s 1977 film has been turned into a shlocky Broadway musical despite a Kander and Ebb score and additional lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda.

Waters believes every Black person must serve as an example. “We need lawyers, doctors, generals, senators!” he hollers at Private James Wilkie (Howard W. Overshown), who can’t help falling short of the sergeant’s unforgiving standards. He’s not interested in overturning the system — he wants to conquer it from inside. And he won’t tolerate any self-pitying excuses from the men under him: “Not havin’ ain’t no excuse for not gettin’,” he proclaims.

Davenport uncovers what happened to C.J. after Waters had him framed for a crime. The extent of Waters’ depravity and the animosity it stoked in his soldiers — especially in Private First Class Melvin Peterson (Tarik Lowe), who somehow wins Waters’ respect by aggressively standing up to him — makes solving the murder all the more challenging. Suddenly, everybody is a suspect.

The play proceeds in flashbacks that are prompted in the interrogation scenes. Time is fluid, sliding regularly into the past and offering even a glimpse or two of the future. Derek McLane’s industrial set conjures barracks life with impressive efficiency and lends the drama a 21st century theatrical sheen.

Leon’s staging indulges in some unnecessary frills. A choral number at the start of the production begins in the dark to minimal effect. Bits of choreography are curiously interjected. Male bodies are paraded seemingly as an insurance package against audience boredom.

The production would be stronger if more effort were made to further individualize the subordinate characters. There’s some blurriness to the storytelling, partly to do with the number of parts and partly to do with the Ahmanson’s large stage. But the core of the play is so solid and the discussion still so urgent that these issues are relatively minor.

Lewis anchors the play with his charismatic smoothness. There’s a nobility to his portrayal of Davenport — even his voice carries a heroic resonance. The only downside is that some of the doubts about Davenport’s decision-making are removed. (It’s hard to clean up corruption without being tainted by it.) At the end of the play, no one can possibly have a clear conscience.

But looking unflappable in sunglasses, Lewis’ Davenport gives the audience a sympathetic focal point. His scenes with Connell’s sharply drawn Capt. Taylor, a foil who turns ally, are infused with tang and tension. In these moments, all that Davenport had to overcome to become an officer is made painfully apparent.

Lee’s take on Waters evokes the powerful memory of Adolph Caesar, who originated the role and reprised his performance in the film. There’s something archetypal about this military character, who uses his power to punish those for sins he objects to in himself. Lee makes this sinister personality somberly and scarily recognizable.

“For as long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to describe Black people in a new way, to destroy all the stereotypical ideas about Black people,” Fuller said in an interview with theater scholar David Savran that was included in “In Their Own Words: Contemporary American Playwrights.” “The idea that anybody, anywhere, can always be described in the same terms is irrational and insulting.”

Fuller, who died last fall, created such an impressive range of Black and white humanity in “A Soldier’s Play” that the work has lost none of its cogency and sting.

‘A Soldier’s Play’

Where: Ahmanson Theatre, 135 N. Grand Ave, L.A.

When: 8 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays, 2 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 1 and 6:30 p.m. Sundays. Ends June 25. (Call for exceptions.)

Tickets: $40-$155 (subject to change)

Info: (213) 972-4400 or centertheatregroup.org

Running time: 2 hours, with one intermission

COVID protocol: Check centertheatregroup.org/safety for current and updated information.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.