In the middle of the last century, designer Paul McCobb seemed to be just about everywhere. His mass-market furnishings, with their thoughtful construction and clean lines — think: “Mad Men” Modernism — graced countless middle-class homes. He designed glassware, lamps and Remington typewriters. And you could read his articles about design in major U.S. newspapers on topics such as the need for more bounce in furniture cushions and how to define a room without cluttering it up, the latter for the Los Angeles Times Home Magazine in 1954.

In 1957, Bloomingdale’s showed 15 of his room settings. Of that showcase, a furniture buyer told the New York Times: “We treat Paul’s furniture like sugar in the grocery store — it’s a staple.”

But unlike some of his fellow Modernist designers, including Herman Miller and Charles and Ray Eames, the Boston-born McCobb didn’t remain a household name. Some of that has to do with the fact that the designer frequently worked in collaboration with different companies rather than solely under his own name. He also died young: in 1969, at the age of 51.

But in recent years, McCobb has made a roaring comeback. Rising interest in his designs has sent prices for his original pieces soaring and led furniture makers to reissue some of his works. The Danish company Fritz Hansen, for example, now carries pieces from the designer’s Planner Group series, which feature slender wrought-iron frames bearing unembellished wood or glass surfaces. Two years ago, CB2 became the first U.S. company to reissue McCobb’s designs — among them, his angular bow-tie sofa, redolent of an age when cars sported fins.

Now, in Los Angeles, you can sate an interest in all things Paul McCobb with a visit to the Paul McCobb Museum.

Though, to call it a museum is a bit of a stretch. This DIY institution is the passion project of a single collector — designer Yogi Proctor — who has turned his Silver Lake home into a singular showcase.

Julie Jackson’s use of reclaimed wood reinforces her commitment to creating sustainable home goods that tread lightly on the environment.

Enter the home and you’ll spot a McCobb chair inspired by Shaker design from 1949 and a pair of pristine armchairs from 1950 that Proctor reupholstered in Knoll fabric from the era. Move on to the dining room and you’ll find a delicate tea wagon (1953) and more Planner Group designs — including a sleek wooden dining table surrounded by chairs whose backrests gently swoop. Nearby, a display features the fabrics McCobb designed for textile producer L. Anton Maix, one of which bears an ebullient rhombus pattern.

The exhibition continues in Proctor’s library and bedroom. “The scope of [McCobb’s] work,” he says, “hasn’t been presented in this way.”

Proctor quietly debuted the museum early in 2022, when he began accepting visitors by appointment — namely, McCobb devotees and design aficionados who heard about the collection through word-of-mouth or design circles. Now the public is invited. On Saturday, he is teaming up with the Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design to host three house tours of his “living museum.”

On a sunny weekday afternoon earlier this month, Proctor eased into a McCobb-designed high-back chair in his library for a conversation (which has been condensed and edited for clarity) about his most treasured pieces and the disaster that inspired him to turn his home into a museum.

What was the piece that got you started on McCobb and where did you get it?

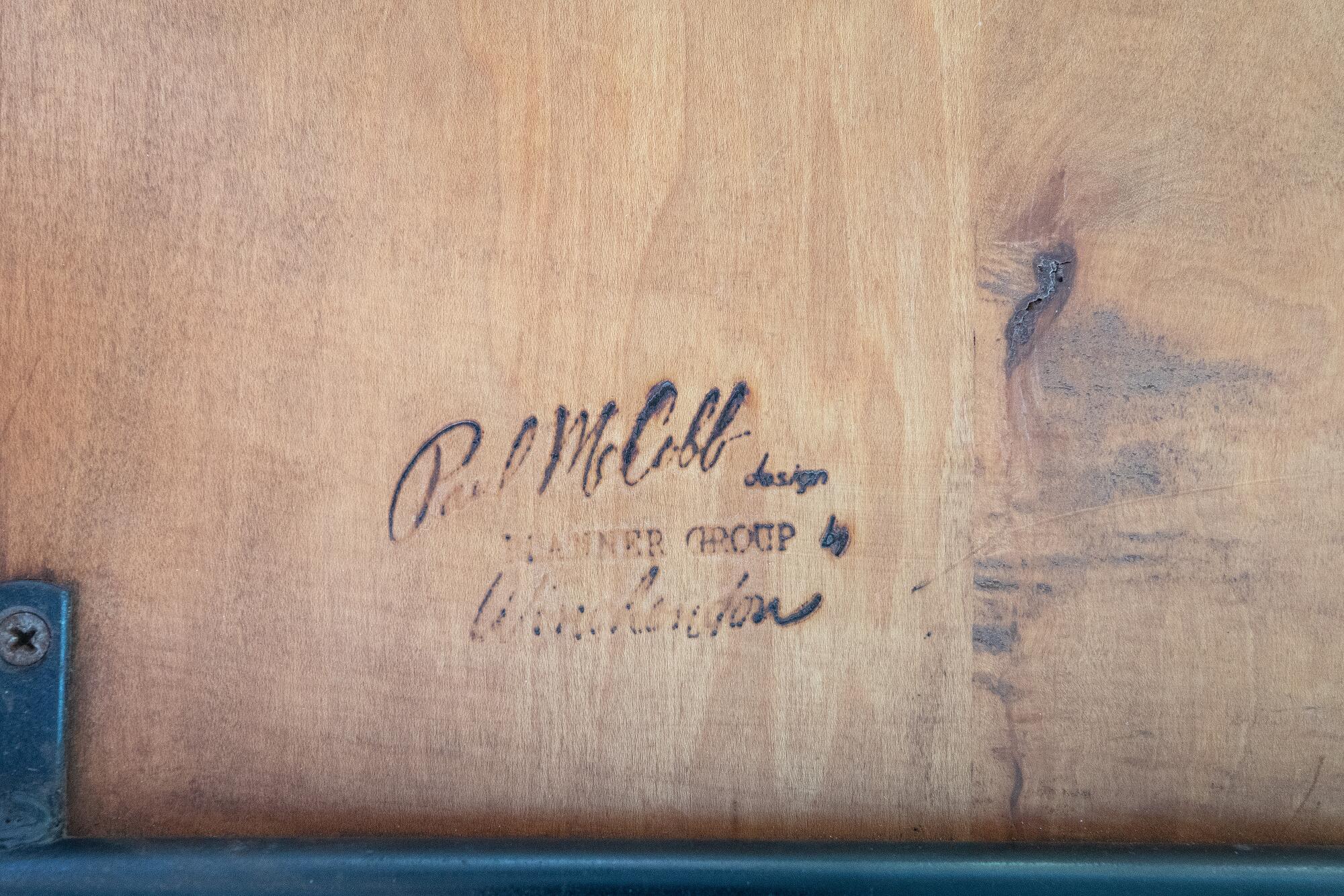

I’m pretty sure it was at the Broadway Antique Market in Chicago. It’s a bench that’s in the middle of the living room, a super simple 60-by-18-inch bench. The appeal was the thin black iron legs and frame and the simple slab of wood on top. It also had a heat brand stamp. This was 18 years ago and there was really no information on [McCobb’s] design and oeuvre. But from the design and the style, I started to piece together that there were other pieces. And then we started to figure out that it’s modular, it’s coordinated and accessorized.

Piece by piece, I built the collection. I collected this archive of materials — catalogs and whatnot — and that was essential for filling out the story. It’s a one-of-a-kind thing.

What makes a Paul McCobb a Paul McCobb?

He would have a lot of quotes about that. Planner Group — the very name is derived from home planning. And it was really aligned with this growing American landscape and this new prosperity after [World War II]. He really designed these pieces for young couples, very budget-conscious. These were innovations at the time: You would buy a piece and maybe add something as your family grew or as your home grew. So, there was this growing relationship. ... It was very accessible.

Also, it was designed for small spaces, with very clean lines. There is an efficiency, a simplicity of form, a structural integrity to it. He isn’t known for singular iconic pieces. The differentiation came from designing collections that fit to a market or a demographic and their needs.

What is your most storied piece?

There are two lamps — lamps were his first pieces. McCobb started after the war, and Paul McCobb Design Associates was really an interior design company and he had a showroom. In designing floor sets for furniture pieces, he started to make his own lamps to go in there. Those were the pieces that got discovered by Irving Richards of Raymor [a distributor of designer products], who said, we need to put these into production.

The lamps I found are early Paul McCobb and they are very handmade. One I found in the background of a photo of a table that was for sale — I think it might have been on eBay or Instagram. I asked if the lamp was for sale and the guy was like, “I guess, sure.” And it was kind of in bad shape. He said, “Are you sure you want the shade? It was really worn.” I was like, “Yes, I want it!”

The other was through Steve [Aldana] at Esoteric Survey, who found it in San Diego, I believe. He put it up online for sale, just listed as a cool lamp at a low price. I spotted it and bought it straight away. I told him that it was an early McCobb lamp for Raymor. Those early lamp designs, there’s a real ambiguous space where I’m still discovering information. It’s in the backgrounds of photos, it’s mentioned in captions. It’s a research project.

‘Migrant Dubs’ was created by Los Jaichackers and shown in the groundbreaking ‘Phantom Sightings’ in 2008. Now it’s a sound studio for DJ Escuby

How did you come to create the museum?

We did a remodel here, which was finished in 2017, and it was kind of done conceptually with a museum project in mind. But then interesting stuff happened during 2020 when the world was turning upside down.

Everything that is out now is about a quarter or a third of the collection. A lot of it is in storage. Well, the storage facility burned down in 2020 and a lot of the collection was lost that summer. I probably should have been more shocked or devastated, but the world was really in a different place. I took it as a sign of, let’s see where this goes.

So, we did an insurance claim and they did five or six interviews, which turned from interviews to investigations. I found my notes for an idea of a museum. I’m explaining it to these insurance investigators who are asking: Why do you have seven sofas? Why do you have 10 side tables? I had to explain to them the idea of what this furniture was.

They honored the claim and I took that as a sign. So I thought, let’s do the museum and rebuild it. It’s the idea of legitimizing this as a design legacy and story and sharing it with the world.

House Tour: Paul McCobb Living Museum

When: Saturday, May 27, at 11 a.m., 12:30 p.m. and 2 p.m.

Where: Silver Lake; address will be shared upon registration

Organizer: Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design

Admission: $25/$10 adults/students

Info: laforum.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.