How Stone Mountain weaponized art against Black people, in a compelling new documentary

In recent years, Confederate monuments around the country have come down. But there is one that stubbornly lingers: Stone Mountain.

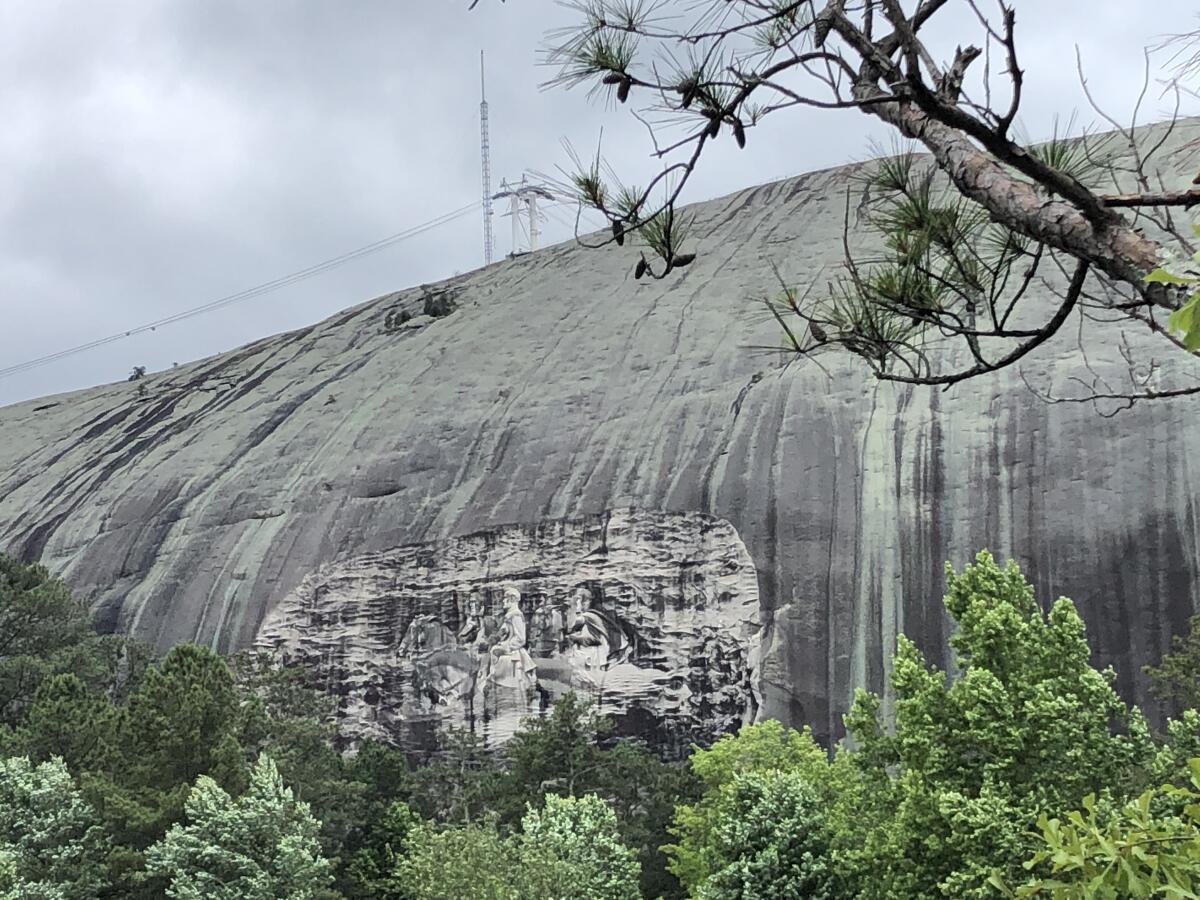

The gargantuan bas relief depicting Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson on horseback appears on a granite outcropping about 15 miles east of downtown Atlanta. Bigger than a football field, the carving has been kept in place by its scale and location. (Removing it would likely require dynamite). It is also enshrined in policy: Georgia law prohibits the memorial from being “altered, removed, concealed, or obscured in any fashion.”

Over the years, various ideas have been pitched to counter or contextualize it, bringing greater nuance and depth to discussions about a site that has long been framed as a monument to Confederate dead but whose entire history is inextricably intertwined with the rise of the modern Ku Klux Klan. Now, a compelling short documentary, produced by the Atlanta History Center, fills out some of the details around this contested site.

“Monument: The Untold Story of Stone Mountain,” which will be available for viewing on the center’s website starting Thursday morning, couldn’t land at a better time. In November, the Stone Mountain Memorial Assn., the state entity that runs the site, announced that it had contracted with an exhibition design firm, Warner Museums, to conceptualize and build a new “truth-telling” display about the history of the monument.

A museum located on site currently features a historical display, but it elides much of the monument’s social context: that it was conceived in the 1910s, in the heyday of Jim Crow, and then lay stalled for decades, only to be reignited by a segregationist Georgia governor during the civil rights struggles of the 1950s. Stone Mountain was also where a group of men — inspired by D.W. Griffith’s racist motion picture “The Birth of a Nation,” which lionized the original Ku Klux Klan — ascended the mountain in November 1915 to burn a cross and resurrect the KKK.

Former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey always wrote of public pain and private struggle. Her memoir, “Memorial Drive,” lets her mother speak.

The monument’s existing exhibition features a single panel about the Klan, framing it as “A Dark Chapter in Our History.” But the Klan is much more than a chapter — think of it as a long-running narrative thread.

At the time of the monument’s establishment, the owner of Stone Mountain gave the Klan unrestricted access to the site for rallies and meetings — access they retained until the state purchased it in 1958. Omitted from the current display is the fact that Helen Plane, who oversaw the Atlanta chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and helped launch the idea of a Confederate monument at Stone Mountain, had once written to the project’s original designer, Gutzon Borglum (who later went on to carve Mt. Rushmore), to encourage him to include Klansmen in the carving — an idea also inspired by “The Birth of a Nation.”

“Since seeing this wonderful and beautiful picture of Reconstruction in the South,” she wrote, “I feel that it is due to the Ku Klux Klan which saved us from Negro domination and carpet-bag rule, that it be immortalized on Stone Mountain. Why not represent a small group of them in their nightly uniform approaching in the distance?”

“Monument,” ably directed by the center’s vice president of digital storytelling, Kristian Weatherspoon, packs all this history into a tight 30-minute film that lays out the story of Stone Mountain, its context and its significance to different constituencies. The movie unfolds through a series of interviews with historians and activists as well as plentiful historical footage — some of it chilling.

Among those featured is Donna Baron, daughter of Roy Faulkner, the carver who saw the monument to completion in the early ’70s. “Sure, there is good, bad and ugly in every story,” she tells the camera. “We just need to continue to focus on the good and not the bad.”

But the doc shows that there is no way to address one without the other, since the very motivation behind building the monument wasn’t to celebrate heroism but to intimidate those fighting for civil rights while advancing the narrative of the Lost Cause.

Most postcards of the huge granite outcropping that rises abruptly on the outskirts of Atlanta dwell on one section: a vast carving of three giants of the Confederacy — Jefferson Davis, Robert E.

“I know that a lot of people think the Confederacy and this monument represent their heritage,” says Claire Haley, who works on democracy initiatives at the history center. “But what I like to remind people is that what we’re talking about what this monument represents — it represents massive resistance to federally mandated integration.”

The intention of creating Confederate monuments, says Brent Leggs, executive director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, “was to weaponize art in support of a false ideology.”

These sculptures served as instruments of terror — a way of showing, as one historian in the documentary puts it, that “the people who had lost the war were now back in charge.”

In her 2020 memoir “Memorial Drive,” poet Natasha Trethewey — whose family once suffered a cross burning — eloquently wrote about what Stone Mountain meant to her Black family in the South. The monument was visible in the distance from her mother’s apartment, “as if to remind me what is remembered here and what is not.”

The Atlanta History Center’s documentary serves as a way of remembering that which has been forgotten — or, perhaps more accurately, unspoken. It follows an earlier effort, from 2017, when historians at the center published a 14-page report offering a condensed history of Stone Mountain that addressed the social forces that had led to its creation — and that still keep it firmly in place.

“Monument” makes that history come to life over an illuminating and gut-wrenching half-hour. And it isn’t simply about the past; it’s about the future too.

Shouldn’t public monuments have public input? In the George Floyd moment, artists and designers are changing the nature of monuments and the histories they honor.

As Sheffield Hale, the president of the history center, says at the top of the film: “Does this park memorializing the Confederacy represent where we as Georgians want to be in the 21st century?”

That is something Georgians will need to reckon with. The first step: to be honest about why Stone Mountain was forged and the hateful messages it continues to reinforce.

“Monument: The Untold Story of Stone Mountain” will be available for viewing on at 6 a.m. Thursday Pacific at atlantahistorycenter.org.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.