Alexandra Grant’s new coffee table book examines what it means to be a civic artist

In 1980, artist Alexandra Grant, then 7 years old, and her mother set out in a red Chrysler LeBaron headed from Washington, D.C., to Mexico City. Her mother, formerly a professor at Oberlin College, was relocating the two of them so she could take a post as a foreign service officer.

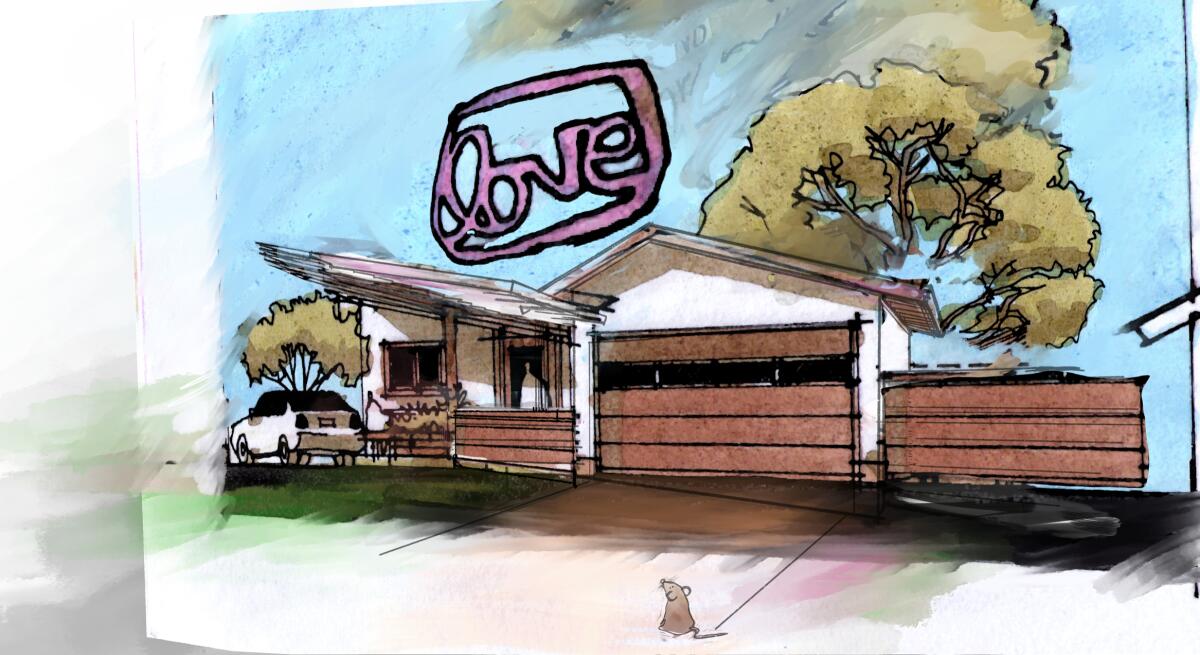

The Beatles album “Revolver” — one of two cassette tapes they’d brought along on the trip — played on repeat. To this day, the song “For No One” holds special significance for Grant. A lyric from that song inspired a papier-mâché sculpture, “A Love That Should Have Lasted,” that Grant created for a 2008 solo show at L.A.’s Honor Fraser Gallery. A photograph of the sculpture, in turn, inspired Grant to trademark what she calls her “LOVE” symbol — a rendering of the word “love,” featured in the sculpture — the next year. Those two images, the sculpture and the LOVE symbol, serve as “the visual point of origin” of Grant’s now-14-year-old grantLOVE project, an initiative that partners with nonprofits to create editioned, love-themed artworks to generate funds for those nonprofits.

The latest iteration in this “sourdough methodology” progression, as Grant calls it — in which each new project or body of work begins with a “starter” from the last — is Grant’s new art book, “LOVE: A Visual History of the grantLOVE Project,” which came out Dec. 6. The oversized coffee table book, published by Abrams’ Cameron Books, is, at its core, about love, but it’s also about art-making, community and giving back. It features photographs of grantLOVE artworks and collaborative projects, along with essays by Grant and curator Alma Ruiz. Writer-artist Eman Alami contributed poems, curator Cassandra Coblentz an interview with Grant. There are also portraits of collectors and nonprofit partners, who offer commentary about the project and its influence.

For a book about philanthropy, “LOVE” is surprisingly vibrant and lighthearted. It has multiple inserts, including a comic by Grant, pull-out temporary tattoos, a sticker and even a cookie recipe.

The book chronicles nearly every grantLOVE project, spanning prints, paintings, sculpture, textiles, jewelry, clothing and architectural endeavors, with partners such as the nonprofits Project Angel Food and Heart of Los Angeles. To date, the project has generated more than $300,000 for U.S. and international nonprofits.

Which may not seem like an earthshaking sum of money over a decade and a half. But as author Roxane Gay points out in the book’s foreword, the project may be small, but “it is mighty, with incredible reach, a powerful mission, and a ferocious heart.”

Here’s what Grant had to say, in this edited conversation, about the new book, the philanthropic project and where it’s headed.

A lot of artists talk about “giving back.” But the grantLOVE project, with 14 years under its belt, is a long-sustained investment of time, energy and resources. Where does your commitment to arts philanthropy come from?

I was raised by many great people and one of them was [godfather] Warren Ilchman — he ran the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University. My godmother was the president of Sarah Lawrence College, Alice S. Ilchman. And my mom was someone who cared deeply about international education. So I was surrounded by political scientists who were always talking about civic society and how do we give back to that. Also, having gone to Swarthmore College and the Quaker ethos of service. So as my art career in Los Angeles grew and grew and grew, I began asking: Well, how do I combine how I was raised, thinking about these issues that come from looking at the bill of human rights and Eleanor Roosevelt as a hero, and move that kind of thinking into the arts? To be a civic artist.

In the book you talk about how, early in your career, you were feeling stretched in terms of giving back. How have editioned artworks been a game-changer in maximizing what you call horizontal philanthropy?

At the beginning of my career, in the early aughts, there were just constant requests for artworks to be donated to different nonprofits, which were all very worthy. I’d look at the photographers and think: Wow, the photographers can donate so many more works because it doesn’t diminish their studio practice — they just donate from an edition. I began to think: Was there a way, in my practice, to create editions that would then work not only to support these arts nonprofits, but to think through this concept of horizontal philanthropy — of an artist engaged in helping other artists. Because philanthropy so often is a vertical — [meaning] with strings attached, or the philanthropist has a vision of how they want their money to be used or what kinds of programming they’re going to support. What I mean by horizontal, is: solidarity. That I’m not putting myself above other creative people. I’m just being a good neighbor and saying, ‘Oh, I have extra of these that we can sell for funds that can support your project.’ So my idea was: Be more in solidarity with my peers and smaller nonprofits. And to be able to do that as often as requested.

Has the grantLOVE project struggled with being taken seriously, given its earnestness? And how do you address that in the book?

To be totally honest, I think people didn’t take it as seriously as they might have just because of so many men in the art world and the LOVE project seemed kind of cute. So now we’ve given about $150,000 to Project Angel Food, and that’s serious because that turns into a lot of hot meals. The different projects we’ve worked with, we’ve raised funds and we’ve brought friends to their missions. And that, to me, is very exciting.

That’s why we included the “Battles” piece [in the book] — to say that it has been very challenging. Not just because of not being taken seriously — I think we have been, especially as the money has become larger gifts — but because, in fact, social media and so much business is predicated by domination systems and by a lack of kindness, whether it’s tabloids or social media itself, the algorithm driven by hate. Love is the issue of our time. I believe it in business, I believe it in how we get along, I believe it in communication. To me, love is not hierarchical.

You have a very deliberate educational agenda, with the project and the book, with regards to arts entrepreneurship for women and other minorities. Can you talk about that?

European friends are always, like: ‘What? American artists have to raise their own funds?’ It is a particularly American [issue] — without state funding, artists really have to become entrepreneurs. So this was a vehicle for me to teach.

What I love about the LOVE project is that it’s really a communication project. For me, the LOVE project is a way to model, for other artists, ‘here’s a very clear way of how to talk about money, create resources for projects, and to model that in the community.’ Because I think, ultimately, the human rights issues that are in the arts are arts education not being given to the people who need creative education the most. And fine arts education continuing not to teach business skills to classrooms that are mostly women and other minorities. So it’s my hope, as a female artist, to show we can talk about money, we can support each other, we don’t have to give away from our art studio practices in order to be part of a circle of community.

Your own art practice spans many mediums. But so much of your work is informed by — and infused with — text. How much of that connection to language stems from growing up between Mexico, France, Washington, D.C., and Spain?

I think it was informed by switching languages and realizing we all have languages inside that are different from the languages that are around us, especially if we’ve migrated. But I also fundamentally believe that we’re all equal. That I’m not above any other person. This fear of the other is so depressing about humans, that fear of other is so strong, especially now with the media and politics being what they are. Those are the two things I’d say an international childhood instilled in me, a humanitarian world view and the experience of not speaking languages.

Taking language one step further, you’re also a book publisher, having launched X Artists’ Books in 2017 with your boyfriend, Keanu Reeves. Why start a book imprint?

X Artists’ Books was born from a real need I found in my life, and in the lives of many peers, to find a home to publish artists’ books. Which there are so many wonderful ways to define, but they are really art works bound between covers. In the first year, we published four different books; we’ve published six books this year alone. We really care about artists getting the book and the communication that they want in order to help build their career, [taking it] one step further from where they are.

You went to high school with author Roxane Gay, lost touch as adults and then reconnected about 10 years ago at a writers conference in North Dakota. Why did you have her write the foreword to the book?

We were out of touch from about [age] 17 to 30. But we were on a panel together and got to hang out at this conference. We’d been watching each other for quite some time and how the other person incorporated all of this kind of loving behavior, whether through teaching, editing, encouraging younger artists and writers. So we were already mutual fans. When I got into the publishing business with X Artists’ Books, that drew us even closer because then I was operating more in her world as a publisher. So it was a no-brainer. When I think of Roxane and the way she thinks about community, both in her personal life and the idea of the civic artist, she emblematizes that to me.

Where is the grantLOVE project headed?

The book makes it very clear I have a long-term vision for the project. That during my lifetime, the LOVE symbol is just gonna be something that I have fun collaborating with people on, and creating, and then when I pass I’ll leave some directives. But my hope is that it will always be a symbol affiliated with wanting to be in solidarity with other creators. My hope with the book, is that people will think, ‘Wow, this is amazing, I want to do something similar in my community.’ It’s a message spreader. It’s a kind of partnering. So whether [that means] lots more LOVE projects, or more people wanting to use their art for being helpful to others, in ways that others want, then fantastic.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.