The ruana is a garment of modest pretensions. A type of poncho common to the northern Andes, it often consists of little more than a simple woolen rectangle with a cut-out for the head. Some are open in the front and worn like a loose shawl; others bear elaborate geometric patterns. When the Colombian Olympic team showed up to the Winter Games in Beijing in February, they made a statement in stylish hand-woven models from an upscale design studio.

But the ruana’s most common purpose is utilitarian. “It is worn by coffee workers and farm workers,” says Carolyn Castaño, a Los Angeles painter of Colombian heritage. “It has multipurpose-ness, too. You can throw it on the ground. You can cover yourself with it. ... You could sit on it at the park and make out on it with your novio or novia.”

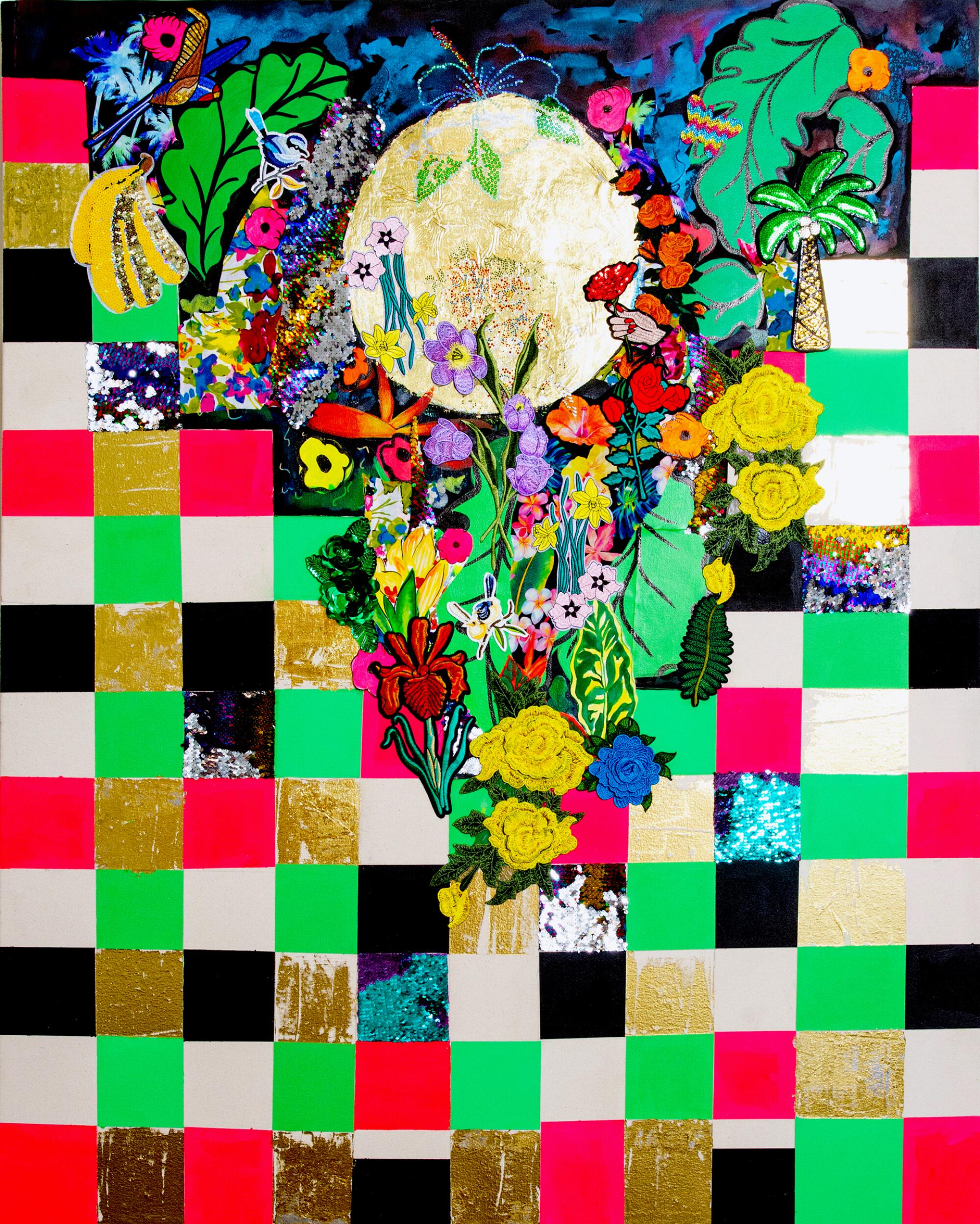

The garment — its dimensions and its design — inspired the works in Castaño’s latest solo show, “Future Ruana,” on view at Walter Maciel Gallery near Culver City. This includes a pair of ruanas of her own invention (stitched together with the assistance of collaborator Stina Peek) that she silkscreened with images of her mother and father. Painted bright hues of green, yellow and pink and layered with hand-painted flowers and appliqués of tropical birds, these sumptuous pieces evoke her family’s migrations between South America and Los Angeles: Cali to Cali, Colombia to California.

But it’s her paintings, displayed over two large gallery spaces, that most captivate.

These use the basic form of the ruana as a point of departure. Around the perimeter of each canvas, Castaño places wild geometric patterns redolent of Indigenous designs and Andean vernacular graphics. (Think of the punchy neon pop of cumbia posters.) At the heart of these, where the wearer’s head might go, she inserts lush landscapes that evoke the tropics. These are rendered in paint but also dense collages of sequins, lace and appliqués. The ruana’s negative space becomes a place for otherworldly landscape.

Can a garment open a door to other worlds? Castaño’s ruanas feel as if they might.

The paintings bring together, in fresh ways, the numerous threads Castaño has been investigating throughout her career.

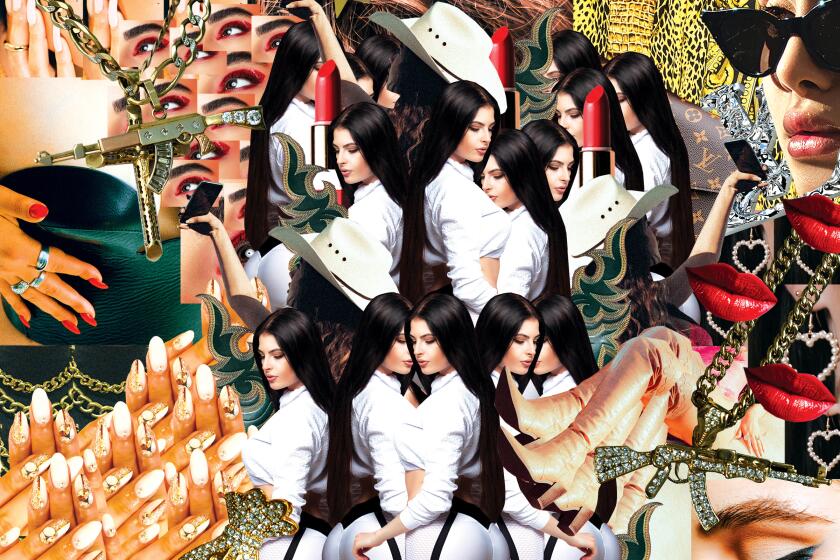

She first drew national attention for the glittery portraits presented in “Phantom Sightings: Art After the Chicano Movement” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2008. Since then, her work has taken on the aesthetics of narco-culture and the hidden politics of landscape painting.

In the fall of 2020, Castaño was the subject of the solo exhibition “Cali es Cali” at the Orange County Museum of Art’s temporary space, but the show fell victim to a surge of COVID-19 and shut down after a few weeks. A version of that exhibition was restaged at Pasadena City College earlier this year, though only for a month. The show at Walter Maciel is therefore a welcome opportunity to delve into the artist’s work.

On a sunny weekday morning, I met Castaño at her Eastside studio, an intimate spot cluttered with natural history books and scraps of textiles. In this conversation, which has been condensed and edited for clarity, she talks about the influences she draws from German naturalists, the garment district shop where she acquires her best appliqués and the ruana that started it all.

The ruana is a form you’ve alluded to in the past. Why did you make that a focus for this exhibition?

For the show at OCMA, I was using photographs and objects from my dad’s archive (which is such a hoity-toity word). But he had a collection of like 4,000 photographs — analog — of L.A. and Colombia. There was a picture of my Aunt Fabiola descending from Mexicana Airlines holding my grandmother’s ruana and she ended up giving it to me. It’s been in my closet. It’s way too hot and heavy to wear in L.A. But I saw the picture and I was like, that’s the ruana!

I wanted to put the actual ruana in the show next to the photographs. When the show went to Pasadena City College, I started to pair the landscape drawings with the ruana shape and the picture of my aunt and I started connecting them.

I was interested in patterns from textiles, especially the colors of the Wayuu [an Indigenous ethnicity from the Colombian region of La Guajira]. They use these psychedelic and fluorescent colors. I was also interested in the shape of the cut-out of the neck. I was interested in the triangle shapes of the neck being an interruption in the European horizontal landscape. So, an interruption, an opening, a vortex, a portal — a speculative tool to imagine another way of interpreting the landscape.

In what ways are you inspired by landscape painting?

I started off being really interested in the drawings and studies of [German naturalist] Alexander von Humboldt and [Hudson River School painter] Frederic Edwin Church, who would kind of paint real settings from his imagination. [Church] would make these composites, which is what I’m doing. I was also interested in Albert Berg, [a German painter] who made drawings of the Magdalena River [in Colombia]. He made these lithographs or etchings of the river, and it’s all very bucolic. It’s paradise. There is no colonialism, no death or destruction. I made a series of drawings inspired by Berg’s drawings, but I’d put a body part in it — like a leg or a hand or a head.

I also love Matisse. He is a big influence. His use of color. His simplicity of shapes and the playfulness. And I love Charles Burchfield’s swamps, which are filled with energy.

Your art has long incorporated materials like glitter and rhinestones. Now you’re weaving in dense layers of sequins and appliqués. What draws you to these materials?

Hanging out with my dad, he had a screen printing business and he’d make posters and doodads for the Guatemalan festival or the Salvadoran festival. He would take me to shops downtown that service the screen printers. It was incredible. If you want to have a T-shirt with gold, you can get this gold foil and you apply it with a heat press. I use it on my canvases now. ... The gold sun shape — it’s gold foil, not gold leaf.

I would also get fabrics from the thrift stores. I’d look for tropical prints. How do they imagine a tropical landscape? I’d go to the thrift stores and try to find as many tropical prints as possible. I love them all.

The Filipino American artist influenced countless students as a teacher at SFAI. A retrospective offers a beguiling peek at his underappreciated work.

What’s your go-to shop for these materials?

The appliqués come from a shop called My T on Maple Avenue downtown. It’s a Korean family who own it: the husband and wife and their poodles. There are a lot of shops on the block, but they have the best. I showed them what I was doing with appliqués and they were like, “It’s a masterpiece!” [Laughs.] They show me what’s new. They got these big orchids that I used in one piece of the show. I’ve also started to learn how to make my own types of appliqués with this sequined fabric I found.

Mexican American art has come a long way since the movement of the 1970s. LACMA’s ‘Phantom Sightings’ traces its zigzag path.

In the past, you’ve talked about a “chromophobia” in Western art — a fear of color. How do you see that manifesting?

As a grad student, when I wanted to use bright colors, it was thought of as “not serious” or kitsch. This was in the early 2000s and late 1990s, this moment in which people were reacting to multiculturalism. It’s this moment in which as an artist, you can have an identity, but not with a capital “I.” So, you can have your personal content, but don’t have it look too Latino. “Serious” art is gray or black and white.

It’s different in other places. [In Colombia,] you see the way the Wayuu use these fluorescent textiles. You walk around Mexico City and you’ll see a magenta painted building or those bright [Luis] Barragán colors. I wanted to create an environment that reflects that way of the world.

I started to bring those elements into my work — you see it in the work in “Phantom Sightings.” I was using glitter. I started using fluorescent colors. I remember talking to [curator] Rita Gonzalez around the time of “Phantom Sightings” and describing it as “Mango Modernism.” I’m, like, give me something with color and a mango print and it makes me happy. But it was also a political move against the hegemony of black and white.

Buchona style, which flaunts consumerist excess, emerged from Mexico’s narco culture and has gone global. Check Jenny69’s viral YouTube single for a tutorial.

In the OCMA exhibition, you drew heavily from your father’s photos. What resonances do you find between those items and your work?

My father would take all of these photos at parties and events. After [he] passed away, I started to organize the photos. It’s incredible how beautiful everybody was. I would notice the architecture and the tilework in my grandmother’s house. There would be these indoor-outdoor spaces. I saw a relationship between the photos he took in Colombia, out on the highway and the street, and the ones here, where he’d shoot the 110 Freeway and the Department of Water and Power building.

In looking at them, I’d see parallels. Sometimes there would be this feeling of being disoriented. Was the photo taken in Colombia or is this in L.A.? That is the feeling of growing up here. I’m American and I grew up here, but I’m Colombian and when I go there they call me gringa. The ruana pieces are a little bit about that. About how immigrants feel — being in two places at once.

Carolyn Castaño: Future Ruana

Where: Walter Maciel Gallery, 2642 S. La Cienega Blvd., Los Angeles

When: Through Oct. 29

Info: waltermacielgallery.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.