As theater economics go from bad to worse, new play development programs are quietly disappearing. The Humana Festival of New American Plays at the Actors Theatre of Louisville, one of America’s preeminent showcases of new drama for many decades, didn’t have its annual event this year and is reevaluating its future.

Sundance Institute Theatre Program, another prestigious theatrical incubator, has been phasing out core activities. And last year the Lark, a fertile off-Broadway center of new work, shut down.

Fortunately, two pillars of new play development remain. On the East Coast, the National Playwrights Conference at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Conn., is still the doyen of the field. And on the West Coast, Ojai Playwrights Conference, once the California upstart, is now in its 25th season as a Shangri-la of playwriting.

What unites the O’Neill and OPC is purity of focus. Both programs are devoted to the gestation of plays, independent of producing considerations.

Many theaters commission and workshop new projects they hope to present on their stages. But a producing interest can obtrude on the artistic process by imposing artificial deadlines and prioritizing the needs of the theater over the work itself.

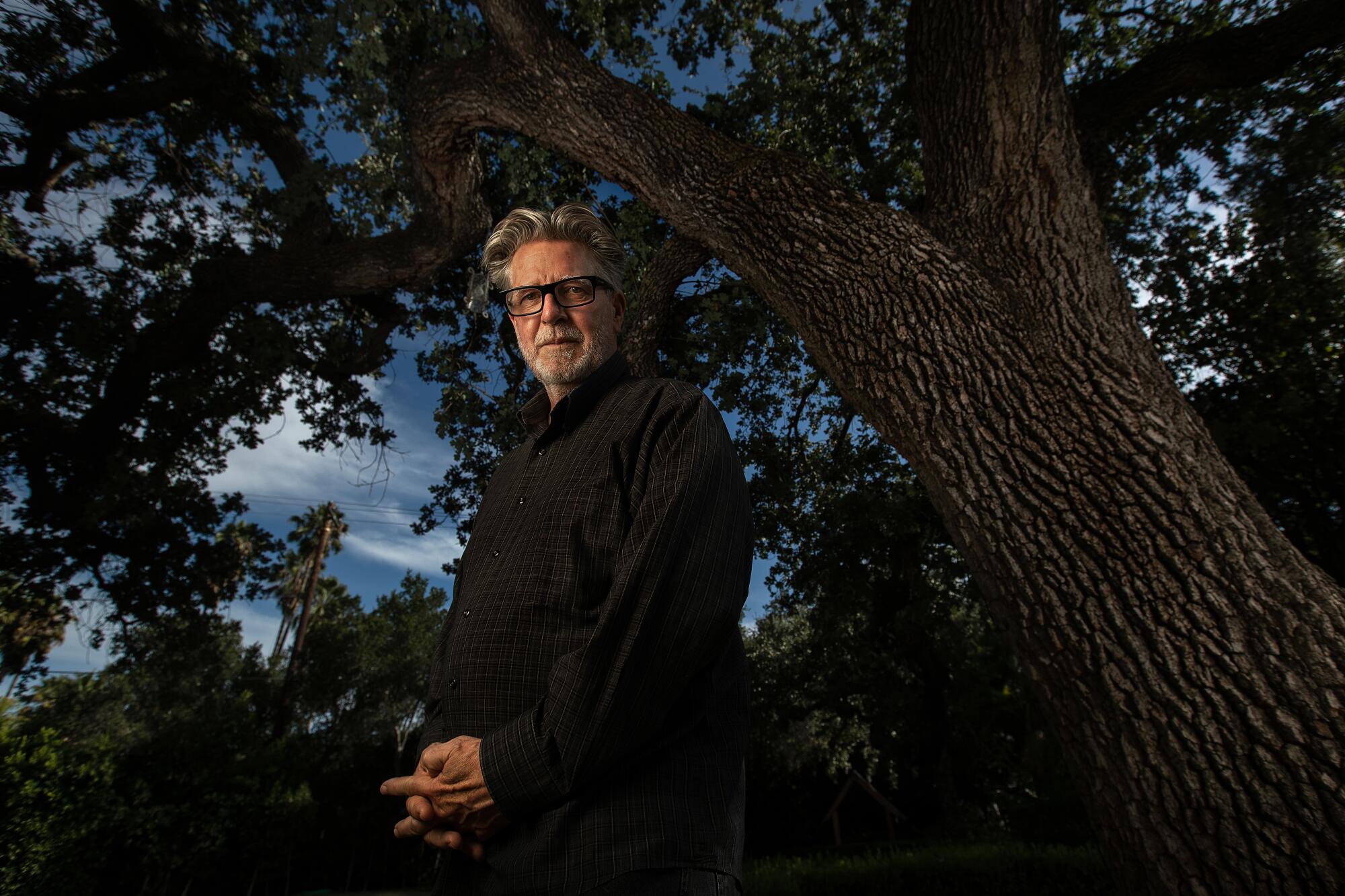

Because the play really is the thing at Ojai Playwrights Conference, there was considerable alarm when Robert Egan, who has served as its artistic director and producer since 2001, announced that he would be departing at the end of this year. Center Theatre Group associate artistic director Luis Alfaro, a playwright who has been an active member of the OPC community, exhorted Egan to protect his legacy.

“I wanted to make sure that Bob maintained the steadfast belief that Ojai Playwrights Conference was invested in writers through their process and not their product,” Alfaro explains. “Bob has a wonderful curatorial vision rooted in new play development that is built in relationship, experiment and in trusting that writers know what they need more than anyone else.”

The roster of dramatists who have come to OPC represents a who’s who of the American theater. Stephen Adly Guirgis, who’s back again this summer, came to Ojai with embryonic versions of his Tony-nominated “The Motherf— With the Hat” and his Pulitzer Prize winner “Between Riverside and Crazy.”

Jon Robin Baitz, another OPC regular, developed “Other Desert Cities,” one of his most critically and commercially successful works in recent years. Danai Gurira, who first came to OPC to work on “In the Continuum,” the play about women and AIDS she wrote with Nikkole Salter, returned with “Eclipsed,” her play about Liberian women and war that defied the odds by moving to Broadway.

Speaking via Zoom from his book-lined study in the converted farmhouse in Great Barrington, Mass., that he is transforming into an arts colony with his wife, Michelle Joyner, Egan was finishing some projects before returning home to Southern California for his final OPC Summer Conference and New Works Festival. The two-week annual event, which brings together a group of working playwrights in a fostering community, culminates in a series of public readings and events (from Aug. 7–14).

He’s been preparing to step down for some time to pursue independent work as a producer of live events, a director with a keen interest in Samuel Beckett and a writer who has earned the right to test his wings in different mediums. But before he ended his tenure, he wanted to be sure that the play development oasis he cultivated would continue to thrive long after he left.

A self-described “child of the ’60s” and an intellectual who studied critical theory with Terry Eagleton at Oxford University after majoring in political economics and English literature at Boston College, Egan describes the atmosphere of the program as “disciplined but with generosity of spirit. We are rigorous but we love you.”

During the conference, playwrights, directors and dramaturgs live and work together. Meeting regularly for meals allows for discussion to happen organically. Serendipity is built into the program along with California sunshine.

Guirgis painted a picture via email: “First of all, OPC is plush. They fly you, feed you, the writers meet at a beautiful poolside library each morning with plenty of breaks to catch a dip in the gorgeous, LARGE, Spanish-tiled swimming pool or play a set of tennis. You eat, sleep, work and play in an environment that is like a first-class spa or wellness retreat. No one wants to leave. And under Bob’s leadership, everything is about the writer and the process. What’s great about Bob is he’s a top-notch, longtime, seasoned pro director and dramaturg but with the enthusiasm of an inspired beginner.”

“Playwrights have a rich field of theatrical talent to tap into,” Egan says. “Guirgis would laugh at me when I would say this, but we are a city of joy. We’re here to help you fulfill your vision. We believe in what you’re doing. Everyone comes to the table with that attitude.”

When asked what separates OPC from the dwindling number of other play development centers, Egan emphasizes the program’s mission: “To develop unproduced plays of artistic excellence from diverse writers both emerging and established, and to nurture a new generation of playwrights. We engage writers who care and dare to confront the great challenges of our day.”

Egan deconstructs this statement with the scrutiny of a literary scholar. “We are unashamedly political,” he says. “Not small ‘p’ political. But capital ‘p’ political. We’re looking to work with artists who deeply and passionately meditate on the relationship between individuals and this very complex thing we call social reality.”

Art that “refracts” rather than “reflects” the world is what Egan is after. “You don’t want to re-create the surface,” he says. “You want to refract it, disturb it, so people are seeing the deeper dynamics.”

Egan insists “that new play development is only as good as the people who do it.” He is quick to give credit to the locals who host dinners and open their guest houses; to the volunteers and interns who keep the operation running; and to the network of theater artists and professionals who generously give their time and loving expertise to bring new work into existence.

“OPC has a talented artistic committee that guides all key artistic decision-making and they join a great reading committee of up to 18 people, who do it for free basically because they love the dialogue,” he says “It’s a great discourse about plays, but with a focus on whether the work serves our mission. Are the plays talking about the world we live in? It’s a highly diverse group, so you’re getting different cultural expressions, insights and articulations of what’s important right now. We’re always learning from each other.”

Before he came to OPC, Egan spent 20 years as the producing artistic director of the Mark Taper Forum. Hired by Gordon Davidson to reignite new play development at the theater, Egan says he succeeded in those years by observing a simple rule: “The table of decision-making power has to be diverse and dynamically reflect the city we’re in.”

“We brought in artists like Chay Yew, Luis Alfaro, Diane Rodriguez, Luis Valenzuela, Lee Richardson, Victoria Ann Lewis, John Belluso, Brian Freeman, Lisa Peterson, Oskar Eustis, and the work we did reflected all those committed people,” Egan recalls. “We became the most diverse theater in the United States of America, and it was the thrill of my professional life.”

Intergenerational and aesthetic diversity at OPC are vitally important to Egan as well. First-time playwrights are placed on equal footing with seasoned veterans. The group is united not by an aesthetic but by a commitment to engaging the world.

“I say this with some reservation, but we’re a content-driven conference in the sense that we’re not as interested in plays that may be formally dazzling but at their heart aren’t agitating from an essence that speaks to equity and justice and community. We love plays that are talking about something essential, and then we doubly love plays that are exciting theatrically,” he says.

Egan cites as an example of this combination Dave Harris’ “Tambo & Bones,” which was at OPC in 2019. The play, which had its world premiere this year in a co-production with Playwrights Horizons and Kirk Douglas Theatre, offers a lively, metatheatrical look on the effects of stereotypical Black stage representations on Black identities.

In a typical year, OPC has development slots for nine plays, with two extra spaces reserved for writers-in-residence. This tabulates into a lot of scripts passing through the program, many of which have gone on to national and international acclaim. But when Egan reflects on his tenure, it’s the relationships with writers that matter most to him.

He speaks ardently of his friendship with Bill Cain, “the most produced playwright in OPC history” and a Jesuit priest “who understands that there are new gospels being written every day and we’re just not listening to them.” And he extols Baitz, his colleague for almost 40 years, for his “commitment to imagining a better America for all in his work.”

Egan traces the evolution of his social conscience from his days growing up in segregated Washington, D.C. Later, in England, when he was mingling with some of the great postwar British playwrights, including Tom Stoppard, David Hare, Howard Brenton and Caryl Churchill, he was galvanized by the way politics and economics were radically reshaping the possibilities of dramatic form.

“I just knew we had to find and support those voices in the United States of America that were wanting to get to a more profound understanding of our country,” he says. “That was the big impetus.”

Does he have any lessons to impart on what not to do when developing new work? Egan speaks of the delicate nature of the feedback process, where one loose remark can throw a writer completely off course. It is for this reason that a strict protocol is observed at OPC in the first week when playwrights, directors, dramaturgs and OPC staff gather for private readings of each play.

“The first level of conversation explores what had impact and generated heat,” Egan says. “The second involves questions the playwright and core creative team (director and dramaturg) might have of the community. And the third dimension happens only if the artist is open to hearing from the room. We ask that any comment is relayed in the form of a question. So instead of saying,’ I don’t think that moment in the second act worked,’ you ask, ‘Why did you construct that moment the way you did? Have you thought of alternatives?’”

When the public is brought in during the second week, the risks intensify. “It’s hard for the audience because they want to judge,” Egan explains. “But I have to tell them, ‘I’m sorry, you’re not here to rewrite the play.’ We want to know what had power, and we want to explore where there are questions. It’s pretty clear from this process where a writer needs to focus, but it’s not painful. I’ve been to playwriting conferences where they bring in a panel of experts to tell you what’s wrong with your work. It’s so ridiculous.”

Egan finds his background in critical theory to be useful on many fronts. “First, we need to enter a playwright’s world and learn its unique language. And then it’s a brilliant structuralist activity. Let’s deconstruct this scene, this character, this moment, to see how it’s operating. A play emanates a range of meanings. It may not be doing what the writer thinks it’s doing. The play itself is autonomous.”

These last words are spoken with a degree of religious awe. And why not? Helping to bring new artistic life into the world is a course in miracles.

A search for Egan’s successor is underway, but it will be a hard act to follow. “To me, Bob is Ojai Playwrights Conference,” Guirgis wrote. “OPC very well may need multiple pairs of shoes to fill his.” But Egan is confident that the organization is on secure footing. The board of directors, which he expanded and shored up, is firmly behind the mission.

“The entire Ojai Playwright Conference community,” he says, “has come to understand the sacredness of what takes place when we gather in those rooms.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.