A man of the church, not the theater, Bach did not write for dance. But dance was at his core. His instrumental suites, partitas and concertos, made of dance forms, can include some of the most profound music of this most profound of composers.

Bach did not write opera either. Yet drama too was at his core. His sacred cantatas and passions, and none more so than the “St. Matthew Passion,” include some of the most profound drama by this most profound of composers.

To dance to Bach comes naturally, as Jerome Robbins, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and many others have lovingly demonstrated. To stage Bach doesn’t come as naturally. But Peter Sellars, in particular, has powerfully proved it can be not just possible but essential.

In 1980, seven years after becoming the director of Hamburg Ballet, American choreographer John Neumeier staged the “St. Matthew Passion” as a balletic medieval passion play in the city’s St. Michael’s Church and then brought it to the opera house. In 1983, it was seen as avant-garde enough for the Brooklyn Academy of Music. By 2005, it had become a classic that suited the glitzy Baden-Baden Festival.

Now, four decades after the ballet’s creation but still rarely seen outside of Hamburg, Neumeier’s “St. Matthew Passion” has reached Los Angeles Opera, raising the further question of where dance, sacred passion and opera intersect. To make matters all the more intriguing, Dance at the Music Center invited Hamburg Ballet to bring along its “Bernstein Dances” to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion for two additional evenings.

Bernstein, it so happens, performed and recorded Bach’s Passion with the New York Philharmonic in 1962 in a what was seen then as a controversial approach and still is. Bernstein cut Bach to enhance the Passion’s theatricality and performed the German text in English. He treated the recitative narration of Christ’s last days as inescapably vivid drama. He brought to Bach’s big choruses and solemn chorales the grandeur of Greek choruses. He unleashed raw operatic passion in soul-searching arias rather than a churchly Passion.

Bernstein questioned everything. The “St. Matthew” was, for him, living, breathing, human theater. But its spiritual essence also got under Bernstein’s skin. That led to his direct confrontation with God in his Third Symphony, written in the wake of the Kennedy assassination, and then in his musically and spiritually transgressive 1972 “Mass.”

Neumeier doesn’t exactly put all this together. “Bernstein Dances” follows Bernstein’s career from his earliest dances and Broadway shows up to “Mass,” but only its “A Simple Song” and “Meditation 2” look at the spiritual side of Bernstein. Along with show tunes and small incidental piano pieces, the main orchestral music is composed of the violin concerto, “Serenade After Plato’s ‘Symposium’” and dances from “West Side Story.”

There are large projections on stage of Bernstein famously conducting with extravagant feeling, something the company’s conductor, Garrett Keast, aggressively attempts to match with a pit orchestra.

For “St. Matthew,” James Conlon more reverently — and more reasonably — conducts the L.A. Opera Orchestra and Chorus along with the Los Angeles Children’s Chorus. The vocal soloists come from the world of opera but sing from the pit.

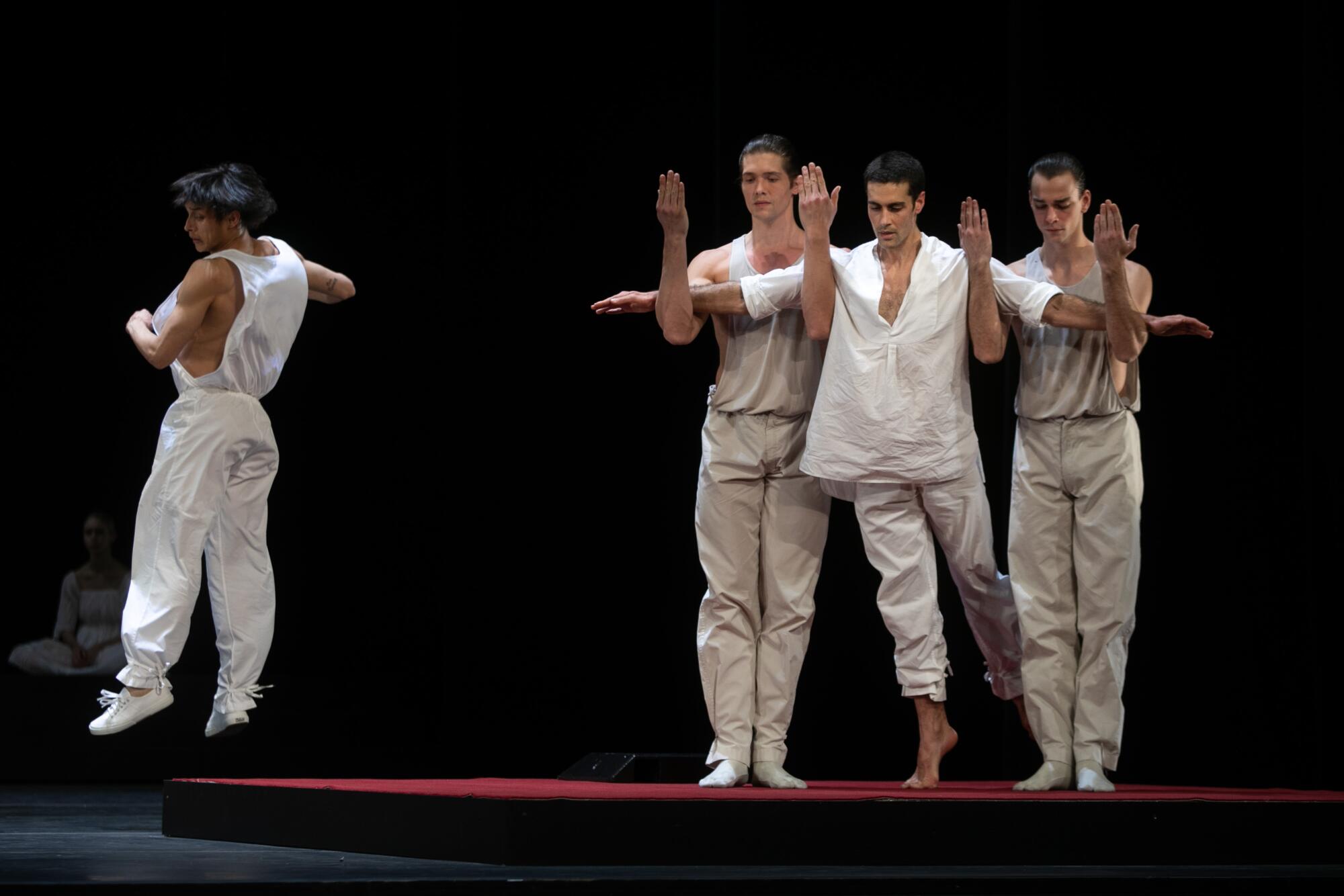

Neumeier is sassier with Bernstein, more stylized with Bach; in “Passion” his dancers, dressed in pristine white, create pictures of elegantly considered classical movement. Bach’s wondrous contrapuntal complexity, full of numerical symbolism and mathematical purity, is mirrored on stage with the dancers assuming architectural set pieces of great beauty.

In both cases, attempts at narrative work less well. Bernstein sits at his piano, tormented, ecstatic and much in between, dreaming of dances that come to life. In one blink-or-you’ll-miss-it instant, Bernstein throws himself on the piano, arms out as if crucified on the keyboard. It’s best to blink.

The incompatible difference between “Bernstein” and “St. Matthew” is the use of music, the main subject of both. In one there is a mishmash of Bernsteinian flair with two singers and pianist on stage, the mood, the method and energy always varied. In “St. Matthew” the music feels less free. The very constraints of dance mean that dancers have to learn choreography to certain tempos. Everything has to fit the movement on stage.

Music requires less expression to let dance have more. That robs personality from the singers, who remain in the pit, hidden to many in the audience. At the March 12 opening, Susan Graham came closest to capturing a palpable depth of feeling in the fervid alto aria, “Erbarme Dich” (Have mercy). Ben Bliss proved a penetrating tenor through it all. But Kristinn Sigmundsson, a worthy Jesus on recording, floundered as bass soloist. Soprano Tamara Wilson sounded lost in the long Passion’s first part but rose more to the occasion in the second.

In the recitatives, in which the Evangelist narrates the Passion and Jesus exclaims in the first person (Joshua Blue and Michael Sumuel, respectively), the singers boomed to make their presence felt if not seen. Nothing can keep down the opera’s magnificent chorus, although placing it behind a scrim upstage, far from Conlon and the orchestra in the pit, reduced its effectiveness.

All of this puts a huge weight on the dancers’ shoulders. Ironically for opera, anyway, they are most emotionally effective when least expressive. When they move with a Bach-directed grace, they could make you believe they were God-directed, and the Passion takes on a gracious spirituality.

But Neumeier’s attempts at symbolism and narrative can also achieve the unfortunate opposite. The dancers are not at their best when they are shown, in one scene, as shackled or required to maintain a saintly disposition while posed as if on the cross. Jesus seated cross-legged as the Buddha in meditation, however, registers as an interesting alternative. Upended benches, the versatile main stage properties that hold the character of Jesus captive, make him look as though he is in a phone booth calling heaven. Chest-beating and bedlam at Jesus’ death has less power to tear at your heart than Bach’s music.

Jesus may proclaim that the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak. For Neumeier, the flesh is never weak, and the spirit isn’t always willing.

And that just might be the choreographer’s great secret. For all his mixed messaging, Neumeier creates a ritual that over four hours grows into a spectacle of ceaseless, rich imagery and movement. Dancers with the stamina and grace to sustain slowly become agents of astonishment. With further performances, the musicians may feel a little freer.

Fight Neumeier if you must. Gripe all you like that a Bach Passion has no place on the lyric stage. Bach wins. This “St. Matthew” winds up being special when it has the right to be and, miraculously, when it doesn’t. St. Lenny doesn’t get off so easily.

'St. Matthew Passion' and 'Bernstein Dances'

Where: Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 S. Grand Ave., L.A.

When: “Bernstein Dances,” 7:30 p.m. March 19; “St. Matthew Passion,” 2 p.m. March 20 and 27, 7:30 p.m. March 23 and 26

Tickets: “Bernstein,” $38-$138; “St. Matthew,” $19-$292

Info: musiccenter.org, (213) 972-0711

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.