Review: Beethoven remade as Black Lives Matter music at the Broad Stage

As long as we have prisons and government, and as long as profit and power remain factors in that equation, we do well to keep the warning of “Fidelio” in our cultural employ. The abuse of power that Beethoven witnessed during the French Revolution and reflected in his only opera reminds us that characters may change over the centuries but situations or motives do not.

In a production that came to the Broad Stage in Santa Monica over the weekend, New York City’s feisty Heartbeat Opera readily transformed the original 19th century Spanish prison setting of “Fidelio” to a contemporary American prison. The political prisoner Florestan becomes Stan, an intellectual Black activist, and the tyrannical governor of a state prison, Don Pizarro, is here a murderous white racist warden.

As such, nothing could be more Beethovenian, even when it came to rewriting the libretto, altering the structure of the opera or adapting the score. The composer, who was shocked by how the Reign of Terror in Paris had voided the ideals of the French Revolution, worked for nine years on his opera, far longer than on any other composition. He produced three versions and felt that he never got this idealistic summoning of freedom entirely right.

Neither have we in the past two centuries. The performance of “Fidelio” I attended Sunday afternoon was on a day when a 21st century reign of terror was raining down on Ukraine, while political activists in Russia are wasting away in the gulag. Updating “Fidelio” is practically a given.

Even so, Heartbeat Opera goes further than most in its radical reframing of “Fidelio.” The company lopped off Beethoven’s beginning and his ending. It reduced the orchestra to pairs of pianos, horns and cellos, which perform along with percussion. In a stunning stroke, Heartbeat recorded real-world prisoners singing the choral parts. When we see them (on video) sing of being released from their dungeon for a brief few moments to breathe the air outdoors, Heartbeat Opera’s “Fidelio” becomes heartbreak opera.

Originally devised in 2018 by the company’s artistic director, Ethan Heard, this is a Beethovenian response to Black Lives Matter. The highly effective cast is mostly Black and given timely dialogue. “Fidelio” being a singspiel, the dialogue is spoken rather than sung recitative. But unlike a Broadway musical or operetta, the drama is resolved in music.

The opportunity to create this new English-language dialogue that portrays modern jail life, while maintaining Beethoven’s score sung in its original German, is the central feature of Heard’s startling concept. Beethoven’s “Fidelio” begins as a comic opera. The jailer Rocco’s daughter, Marzelline, rejects the advances of a gatekeeper, Jaquino, because she’s besotted with her father’s new assistant, Fidelio, who is really the prisoner Florestan’s wife, Leonore, disguised as a man in an attempt to save her husband.

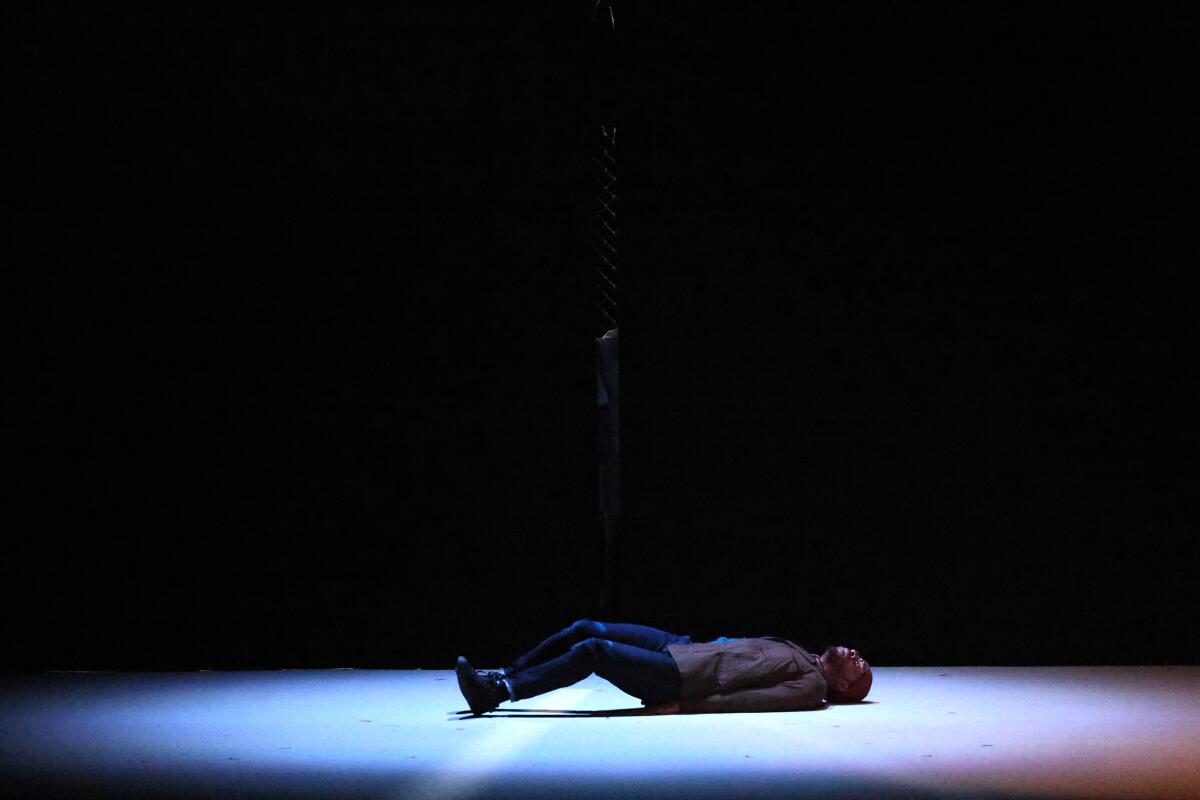

Rejecting a lighthearted start, however, Heartbeat begins with strobe lights and gunshots, violent flashes of Black people taken prisoner. Leonore (renamed Leah in Heartbeat’s version) sits at her computer online with a lawyer trying to get justice for Stan, arrested on a trumped-up charge because he had investigated the white supremacist background of the warden Pizarro. Stan has been kept in solitary, allowed no communication with Leah or the outside. The case, she is told, can’t be won.

She is furious and dreams of herself as Beethoven’s heroine, his symbol of freedom, who frees her husband. She has no need for male disguise. Marcy has come out. Her jovial father, Roc, eggs on the romance.

The music begins with a sublime trio (originally a quartet) that is Beethoven’s third number, an unexpected moment of wonderment. Music comes across as the world of imagination. A marvel of this production is how the opera drives the drama more than the realistic play surrounding it.

Reality and opera get the most profoundly confused when on a white sheet we see projections of prisoners’ choruses. Artistic Director Heard and Music Director Daniel Schlosberg visited several Midwest prisons, and 100 inmates are seen singing in German with scores in hand.

We know nothing about them, who they are, why they are there. They are young and old, men and women, Black and white and brown, focused intently on Beethoven, and doing a better than credible job.

It’s a transformative moment, hard to put into words, but, in fact, put into words by the members of the choruses. Handwritten letters about their experience were displayed in the lobby. “The creativity I possess is still within me,” writes one inmate, who described his chorus as “a motley crew of men trying to rise above their situation.” His conclusion surely would have moved Beethoven: “Prison has not taken away my hope.”

This “Fidelio” does not flinch at hard questions. Derrell Acon’s powerfully sung and revelatory Roc, a corruptible enabler of Pizarro, proved a particularly disturbing personification of the banality of evil. Kelly Griffin’s Leah transformed Beethoven’s Leonore into a fanciful power-to-the-people wonder woman. Curtis Bannister’s Stan chillingly captured the torment of injustice. For Corey McKern’s Pizarro, evil was not banal. The virtue of Victoria Lawal’s Marcy was to unearth the banality of administrators.

Schlosberg’s arrangement for the seven-piece ensemble, which he conducted from one of the pianos, displayed much invention, but percussion punctuation and purposeful horns tended to make their points in the musical equivalent of all caps and boldface.

This “Fidelio” does not accept Beethovenian triumph. Instead of the wishful-thinking climactic chorus at the end, Leah wakes from her dream. For Beethoven freedom was a vision, and that vision for betterment is what drives us. Leah, her vision vanished, is driven by anger, possibly playing into exactly what Beethoven feared — that even righteous power, as with the French Revolution, can lead to abuse.

Beethoven required a justice beyond power. It is no coincidence that he could, even today, give prisoners hope.

Letters from the choristers can found on the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where the production was performed. And yet another new look at “Fidelio” is around the corner, when Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic mount Beethoven’s opera next month with Deaf West Theatre.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.