Review: The theater world is finally ready to experience Alice Childress’ ‘Trouble in Mind’

San Diego —

Alice Childress’ “Trouble In Mind” is the best new play I’ve seen in ages.

Yes, I’m aware it was first done in 1955, but the play is only belatedly receiving its due. American theater is at long last ready to listen to a playwright who was calling out systemic racism decades ago in a backstage comedy that is as biting as it is entertaining.

The Broadway premiere, unconscionably delayed more than 60 years, happened last fall. Omicron foiled my plans of seeing Tony winner LaChanze star in the Roundabout Theatre Company production, so I was grateful for the opportunity to catch a different production of the play at San Diego’s Old Globe Theatre.

This skillfully written work was worth the Saturday traffic. The production, directed by Delicia Turner Sonnenberg, honors the way Childress balances comedy and drama, argument and story, politics and psychology.

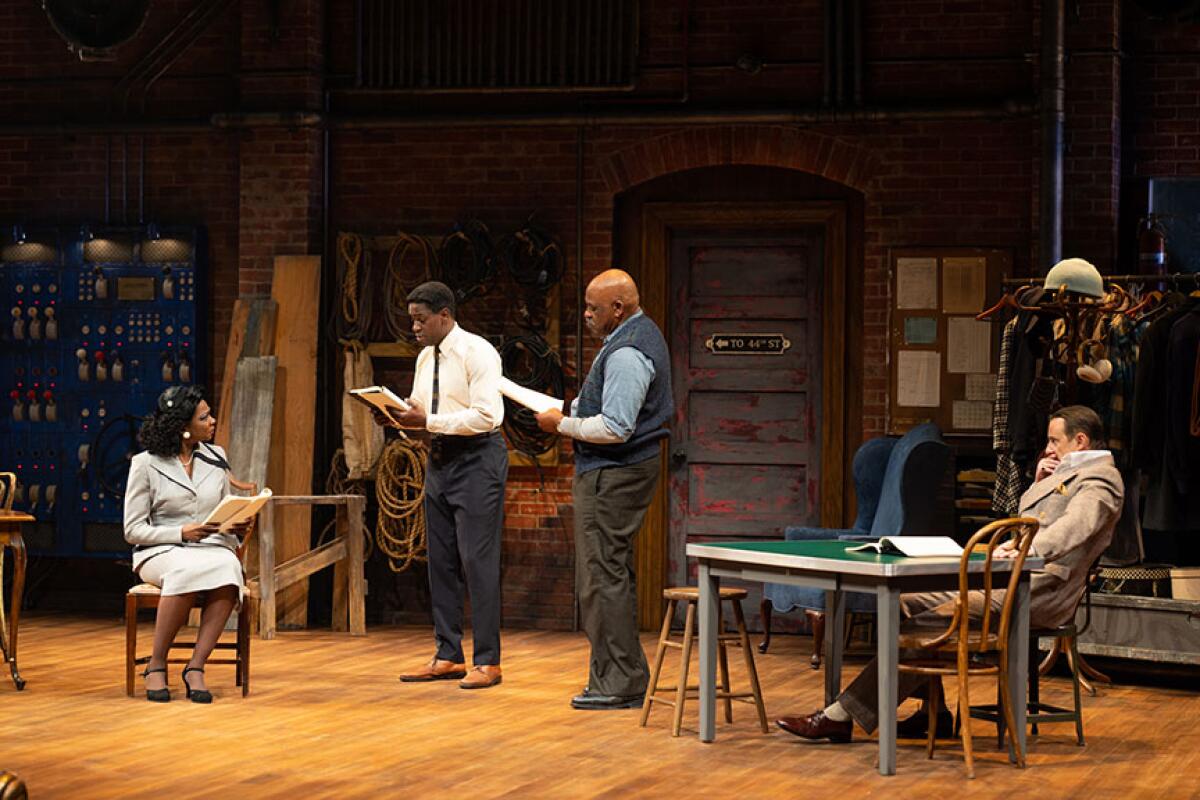

The plot revolves around the rehearsals of a play that is written by a white playwright, directed by a white director and performed by a cast of four Black and two white actors. The subject of “Chaos in Belleville,” the play within the play, is lynching in the South. It’s meant to teach white audiences a thing or two about right and wrong — and to get white theatergoers to sympathize with Black folks.

The director, Al Manners (Kevin Isola), eager to make a humanitarian statement after some difficulties in Hollywood, challenges his actors to be clear about the intentions behind their lines and actions. He wants the truth to flourish. Unfortunately, “Chaos in Belleville” is a profoundly dishonest work, a play so concerned with winning over white audiences that it neglects the basic reality of its Black characters.

Childress focuses on the dynamics among the ensemble members. The Black performers, happy to be working on Broadway, don’t want to jeopardize a paycheck. But their tolerance for hypocrisy varies.

Wiletta (Ramona Keller), a middle-aged actress who’s earned the right but not the privilege to be a diva, advises John (Michael Zachary Tunstill), a neophyte actor eager to make his mark, to laugh at the director’s jokes, though not too much. She tells him to suppress his real opinion about the play, offer lavish praise whenever possible and not take the job too seriously.

“Sounds kind of Uncle Tommish,” he replies.

“They call it being a ‘yes man,’” she explains. “You either do it and stay or don’t do it and get out.”

Millie (Bibi Mama), another experienced actress, is bolder with her opinions. She has little patience for Sheldon (Victor Morris), a shambling old actor who believes Black people have to swallow their pride simply to survive. But Millie turns out to care more about nice clothes and attractive watches than principles, while Sheldon manages to sneak in a couple of devastating remarks amid all his servile flattery.

The white company members are drawn with the same comic nuance. Judy (Maggie Walters), a recent graduate of Yale’s drama program who doesn’t know the difference between downstage and upstage, is liberal in her thinking but somewhat less progressive when she feels under attack. Bill (Mike Sears), a busy character actor, insists he doesn’t have a prejudicial bone in his body, but don’t expect him to eat lunch with his Black cast mates.

Henry (Tom Bloom), the old Irish doorman at the theater, treats Wiletta like royalty. A former stage electrician, he once rigged up the lighting for one of her musical numbers and is still dazzled by the memory of her performance. Eddie (Jake Millgard), the browbeaten stage manager, also displays a courteous streak that, in the fraught atmosphere of Broadway, is the exception rather than the rule.

Childress ratchets up the tension between Wiletta and Mr. Manners, who exhorts her to authentically inhabit the reality of her character. Wiletta’s go-along-to-get-along philosophy is put to the test. She’s asked during a heated rehearsal to justify her actions in the play, in which she basically allows her son, whose only crime is having voted in the South, to fall into the hands of a lynch mob.

Wiletta knows that’s not how any mother would act, but making this point threatens to unravel any notion that “Chaos in Belleville” is worth doing as written. Forced by her director to be more truthful, she has to choose between integrity and economic security — not just for herself but for everyone in the company.

The conflict in “Trouble in Mind” is clearly delineated, but there’s nothing schematic about the work. Childress, who was an actress before she became a playwright, individualizes every character with economic strokes. The humanity on display is too affectionately messy to fall into ideological camps.

Race is at the center of this theatrical struggle in a way that echoes the cultural reckonings that have been taking place on Broadway and in theaters around the country over the last two years. Indeed, it’s astonishing how contemporary the discussion seems, as though Childress had been taking notes at recent meetings of activist organizations such as We See You, White American Theater.

But the sad truth is that not much has institutionally changed since Childress wrote the play. Attitudes may have evolved, but discriminatory practices have stubbornly held on in an art form in which power remains largely in white hands.

Everyday gender inequities are glimpsed in this rehearsal room, as are the struggles of artists, white and Black, to make work that matters. Even Mr. Manners gets the opportunity to vent his own grievances. No one feels fairly treated, but degrees of unfairness are carefully observed.

This breadth of detail is captured in Turner Sonnenberg’s production with an admirable modesty that always puts the play first. This is a true ensemble effort. It was only toward the end that I began to fully appreciate the high caliber of the performances, most especially Morris’ sneakily subversive Sheldon, Isola’s arrogant Mr. Manners and, of course, Keller’s splendidly simmering Wiletta, who is compelled to say what no one in charge is ready to hear.

Childress, who died in 1994, understood Wiletta’s predicament because she had to live it again and again. To accommodate the demands of producers who insisted on a happy ending, she revised “Trouble in Mind” for its off-Broadway run. But she regretted the changes she made, and when she published the play, she restored the original ending that left unresolved the outcome of the rehearsal struggle.

A Broadway production was optioned later on, but again revisions were insisted upon. Childress did her best to comply, but several drafts later she didn’t even recognize the play anymore. Producers eventually dropped out, and Childress lost heart.

On the long drive home, I contemplated Childress’ drama with both gratitude and sorrow. My admiration for the excellence of the writing was tinged with mournfulness for a writer who deserved better in her lifetime.

How is it that I’d never, until 2022, seen an Alice Childress play in performance? Well, we know how. “Trouble in Mind” answers that question too.

'Trouble in Mind'

Where: The Old Globe, 1363 Old Globe Way, Balboa Park, San Diego

When: 7 p.m. Tuesdays-Wednesdays, 8 p.m. Thursdays-Fridays, 2 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 2 and 7 p.m. Sundays. Ends March 13

Tickets: Start at $29

Info: (619) 234-5623 or theoldglobe.org

Running time: 2 hours (including intermission)

COVID Protocol: Proof of full vaccination is required, or a negative test result from a COVID-19 PCR test taken within 72 hours of showtime. Masks are required at all times.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.