Commentary: No, ‘Grand Canyon’ isn’t better than ‘Crash.’ In fact, it owes Los Angeles an apology

“Grand Canyon” struck a nerve when it hit movie theaters 30 years ago.

With a starry cast that included Kevin Kline, Steve Martin, Danny Glover and Mary McDonnell, the 20th Century Fox release was hailed by critics as an edgy, violent portrait of upheaval and racial tensions in Los Angeles. With its multilayered story and scenes depicting traffic gridlock, gang violence, earthquakes and the Los Angeles Lakers in “Showtime” mode, “Grand Canyon” was ambitious and provocative, going where few major films dared to go. The screenplay, by director Lawrence Kasdan and his wife, Meg Kasdan, earned an Oscar nomination.

Kasdan regards “Grand Canyon” as a hallmark of his career, which also includes “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” “The Empire Strikes Back” and “Body Heat.” He and several cast members celebrated its legacy in The Times last week, saying the film should be held in higher esteem than the later, similarly themed — and Oscar-winning — “Crash.”

‘Grand Canyon,’ a tale of two very different views of Los Angeles starring Kevin Kline, Alfre Woodard and Danny Glover, turns 30 this month.

But in the wake of the racial tensions now roiling the country and the momentum of the Black Lives Matter movement, “Grand Canyon” should be seen for what it is — an unapologetic paean to white privilege sprinkled with offensive images and racist depictions of Black life. As it did when it was first released, its perspective reflects the overwhelming terror of upscale white professionals that urban chaos is jeopardizing their idyllic lifestyle.

In “Grand Canyon,” dark-skinned people are the enemy and the other, preying on affluent whites. Inglewood is a blighted community of ominously dark streets, marauding gangs and abandoned cars. Black fathers are absent, and the only life young Black men aspire to is thug life. The buzz of circling police helicopters with bright spotlights is constant. Drug deals take place in open daylight outside fenced-off playgrounds.

Black residents live in cluttered, cramped homes with iron bars on their windows and doors, while white households are spacious, clean and plush. The only salvation for Black folks is from generous white saviors.

‘We have to see what Mamie saw,’ ‘Women of the Movement’ creator Marissa Jo Cerar explains of the scene, with Adrienne Warren as Till’s mother.

“Grand Canyon” wastes no time in its opening scenes announcing its fear-based vision. Successful immigration lawyer Mack (Kline) gets lost taking a shortcut home from a Lakers game at the Great Western Forum. He is immediately stalked by shadowy figures blasting N.W.A from their white BMW. His car suddenly stalls, and when he calls for roadside service, the operator hangs up after hearing he’s somewhere in Inglewood.

As Mack waits for a tow, the BMW pulls up behind him and the gang inside, including its armed leader Rocstar, surrounds Mack’s car. But before they can harm him, a tow truck arrives. Carrying a large crowbar, Simon (Glover) calmly steps out and hooks up the Lexus to the truck. He then takes Rocstar aside, asking him to “do me a favor” and allow him to take Mack and his car away.

“Are you asking me a favor as a sign of respect,” says Rocstar, “or asking me a favor because I got the gun?”

When Simon tells him there would be no negotiation if he weren’t armed, Rocstar says with a sneer: “That’s what I thought. No gun, no respect. That’s why I always got the gun.”

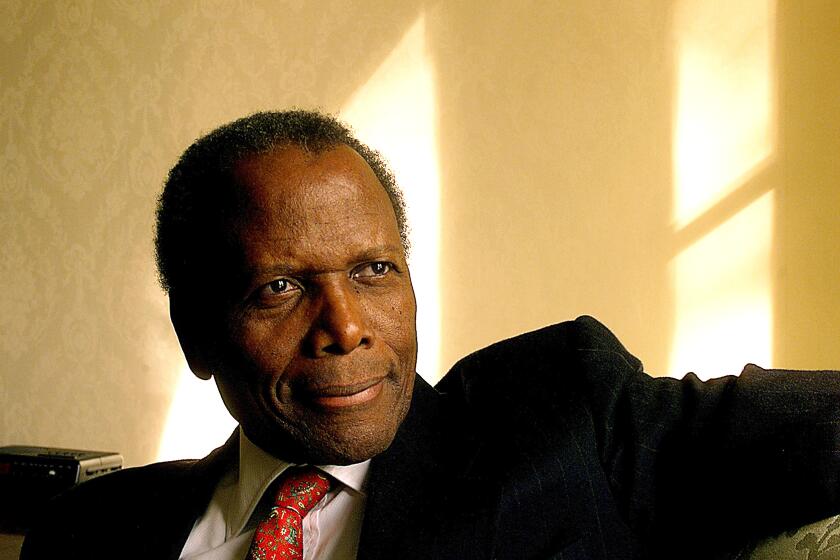

Reporter Greg Braxton recalls the nerves, awe and finally calm that accompanied an interview with Sidney Poitier in 2000. Poitier died Thursday at 94.

Mack’s teen son Roberto (Jeremy Sisto), named after baseball legend Roberto Clemente, later tells his father, “Lucky you got out with your life. It could have been curtains for you.” In the vast kitchen of his Brentwood home, Mack tells wife Claire (McDonnell), “The night when I thought those boys were going to kill me, I realized I f— hate immigration law.” (Mack is never shown doing any legal work.)

Inglewood officials in 1992 were infuriated by the depiction of their city as a crime-ridden ghetto, calling it an “assassination of an entire municipality’s character” and “a dangerous display of social irresponsibility.” They threatened to ban film production in the city unless the producers apologized.

That apology never came.

The movie was just getting started. Davis (Martin), a movie producer specializing in violent fare, works on his latest film where a hoodlum named Skin (Henry Kingi, co-founder of the Black Stuntmen’s Assn.) and his white accomplice shoot up a bus filled with riders. Later, Davis is shot and seriously wounded by a Latino robber.

Simon’s young nephew Otis (Patrick Malone) refuses to give up the outlaw life despite his uncle’s warning: “Without my set, I’m nothing. They care about me, man.” After Roberto meets the parents of the blond girl he fell in love with at camp, he tells his mother, “I think they were relieved I wasn’t Puerto Rican.”

The contrast between white and Black communities is sharply drawn. In Brentwood, neighbors worry about their chandeliers falling after an earthquake. But in Inglewood, a woman is shown scrubbing a huge puddle of blood off the sidewalk.

As payback for Simon’s rescue, Mack maneuvers to help his sister, single mother Deborah (Tina Lifford), and her family move from their gang-infested neighborhood into a safer — and whiter — neighborhood in Canoga Park. He also sets Simon up with Jane (Alfre Woodard), a secretary he barely knows. Although the gestures are intended to be noble, they are actually patronizing, the white savior rushing in to rescue the helpless Black victims.

Kasdan admitted in a 1991 Los Angeles Times interview that the screenplay was inspired by fear of the growing encroachment of urban growth and communities of color on whites.

“Cities are supposed to be hubs of civilization, not war zones,” he said. “In Los Angeles, we had the fantasy that we could run to our neighborhoods and hide, but that illusion has been dispelled. One wrong turn plants you in enemy territory. There is no safe place anymore, no sense of security. ‘Grand Canyon’ is about the fact that we’re all interconnected. If people at the bottom suffer, we all do. The world becomes an unlivable place.”

A 1992 Washington Post profile of the Kasdans said the couple wrote “Grand Canyon” as a way to explore “race and fear in America in a way that would engage an audience without striking any poses or reaching any conclusions.”

“The Kasdans had little firsthand experience with life in predominantly Black and Hispanic south-central Los Angeles, a key location in the film,” the article said. “They wrote from what Meg Kasdan called ‘our perception and our belief that people share concerns, regardless of their race,’ but they also found a minister working in the crime-ridden area who introduced them to some gang members.”

“This film was written from my gut,” Lawrence Kasdan said in a featurette included on the DVD of the film. “It’s about my own surprise at the way the world is, as opposed to the way I thought it should be.”

Those comments expose the film’s true — and dangerous — message. In seeking to provoke more interest in “Grand Canyon” decades after its release, the Kasdans demonstrate their lack of interest in gaining genuine insight or understanding of the complexities of race relations in America. They still believe in the same vision of a Los Angeles plagued by crime and economic despair, projected from within the high walls of their artistic suburban fortress.

In The Times’ story on the film, “Grand Canyon’s” Black performers are supportive of the film. Glover and Woodard praise it as a work of honesty and Kasdan for allowing them to help form their characters. Said Lifford: “The movie absolutely captures and represents a known reality.”

Kasdan said he doubts that he, a white man, would be allowed to make a movie like “Grand Canyon” in 2021.

I’m thankful he got one thing right. But it’s not too late for that apology.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.