Review: Ex-President Trump claims to be a witch hunt target. These feminist artists beg to differ

How many times over the last four years has twice-impeached former President Trump uttered the words “witch hunt”?

A hundred? A thousand? A bazillion?

In 2018, as the Robert S. Mueller investigation into Russian collusion and obstruction of justice heated up, an avalanche of Trump tweets claimed he was the innocent focus of a hysterical cabal, not unlike the poor residents of 17th century Salem, Mass., 20 of whom (mostly women) were hounded into early graves from unfounded accusations of sorcery.

He’s continued ever since.

A Vox story on the disgraced president’s unceasing usage of the term witch hunt aptly noted that there is “something distasteful about men in power — particularly [those] credibly accused of sexual assault — using a term that harks back to an era in history in which a patriarchal society wrongfully persecuted (mostly) women.”

Stacy Schiff, the author of a book about Salem entitled “The Witches,” explained to the publication: “We’ve turned the expression on its head. Traditionally a witchcraft charge amounted to powerful men charging powerless women with a phony crime. Now it is powerful men screeching that they are being charged with phony crimes.”

The curators of the often cheeky but nonetheless serious exhibition “Witch Hunt” would likely concur. Their show’s snappy title, wrapping recent art by 16 women within a familiar sobriquet shrouded with hostility in order to defuse it, is anything but a coincidence.

“We began with a question,” the exhibition catalog announces. “What does it mean to be feminist in the age of Donald Trump?”

On view until Jan. 9 at the UCLA Hammer Museum in Westwood and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, across town, the show brings together international artists — the 16 were born or work in 13 countries as far afield from one another as Brazil, Germany and South Africa — who reflect the diverse experiences of women’s lives in patriarchal societies today. Most are Gen Xers, born in the media-saturated 1960s and 1970s, who grew up during feminism’s so-called third wave.

That wave has now passed. This selection underscores that advocacy of women’s rights on the basis of equality of the sexes has been supplanted. The old binaries have given way, opening up myriad new paths. Feminisms — plural — proliferate.

Two works are exemplary. Shu Lea Cheang — at 67, the senior artist of the group — dives deep into the futuristic digital sea to swim among the elusive pixels. Candice Breitz heads in an almost opposite direction, rethinking the physically and psychologically demanding nature of sex work — the world’s putative “oldest profession.”

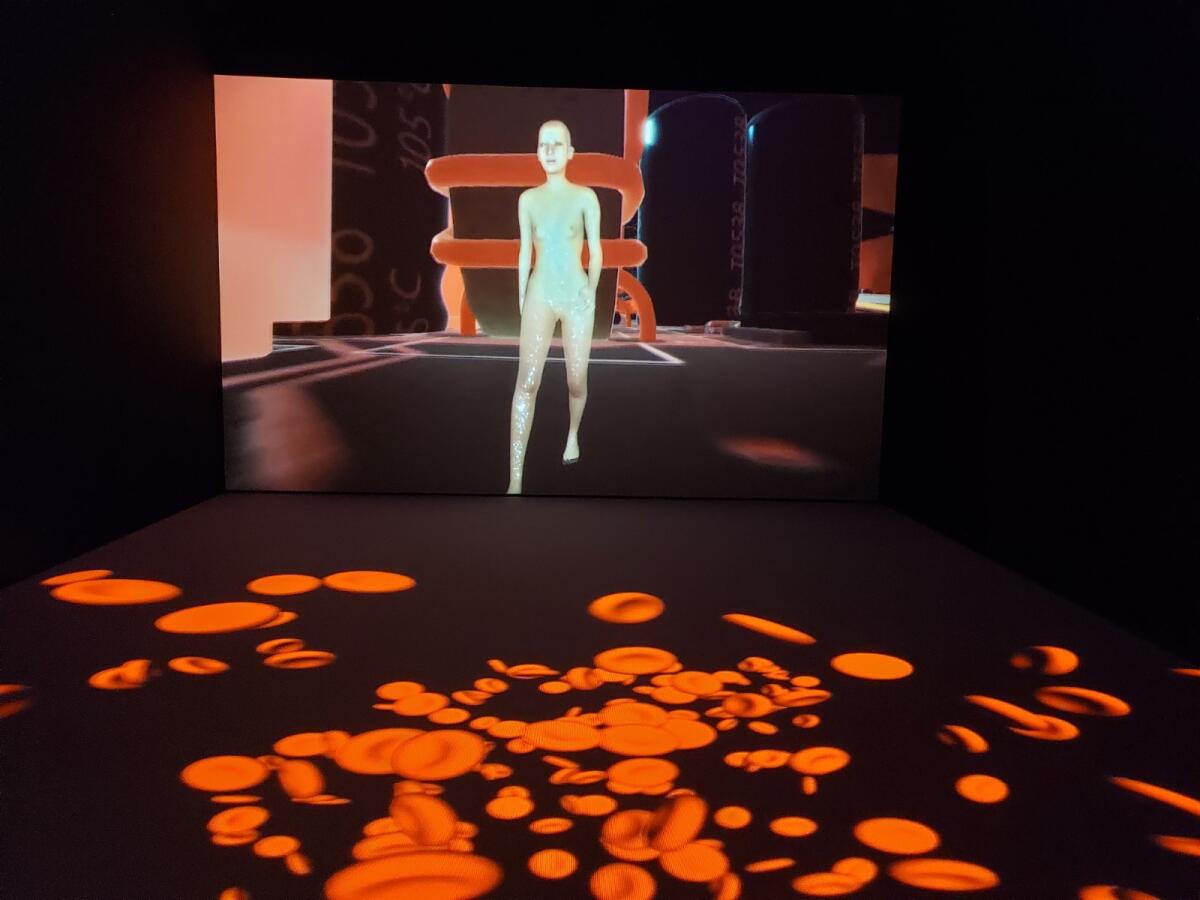

Cheang’s gripping “UKI Virus Rising” projects vivid red globules onto a darkened gallery’s floor, the swarming organic shapes like a gigantically enlarged blood sample sliding underfoot. To the thumping sound of a foreboding electronic score, the end wall features a 10-minute video projection of a bleak and constantly changing landscape composed of a computer’s innards, through which a female-appearing android moves.

Suddenly she transforms into a tree, recalling Bernini’s Daphne escaping rape, from Ovid’s “Metamorphoses.” Slowly she becomes a circuit board, buzzing and pulsing. Finally, she transmutes into a virus — a female bug in a hard-wired social system. Maybe the computer virus will bring the whole system down, or maybe bring it to heel.

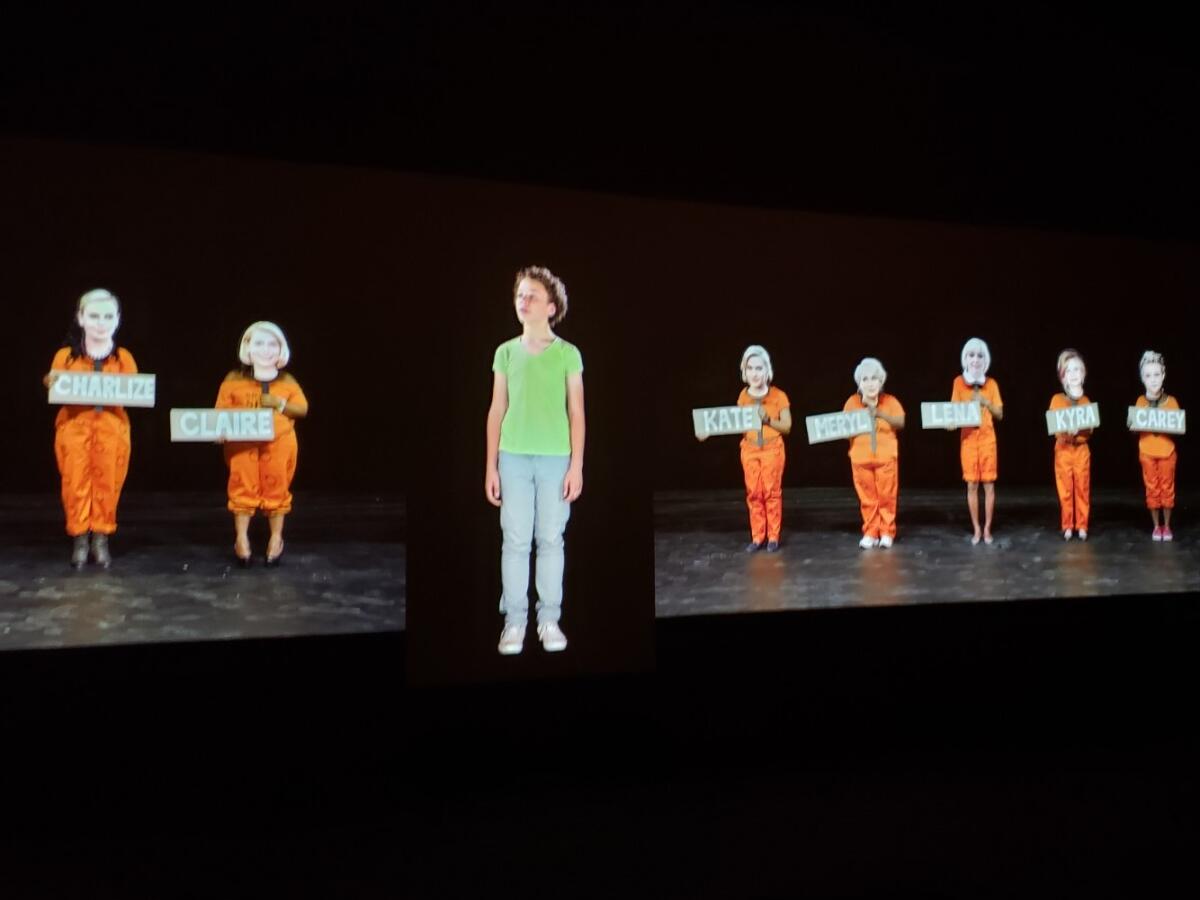

Breitz assembles a cast of South African sex workers, mostly Black and not entirely female, who line up across a wide video projection. They’re a Greek chorus commenting on the moral issues raised by a charismatic, startlingly self-possessed young woman at the center.

At one point they don masks of Meryl Streep, Lena Dunham and other white Hollywood feminists who once lobbied to stop legalization of Cape Town prostitution. The sex workers chastise the well-meaning celebrities’ denigration of labor. “Sex work is work,” they insist.

To underscore that these are varied feminist themes rather than a presentation of one singular conception, curators Connie Butler from the Hammer and Anne Ellegood from ICA L.A. effectively present the exhibition as a collection of 15 solo shows. (Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz work as a team, their 20-minute video homage to electronic music pioneer Pauline Oliveros a theatrical marvel in which the props, lights, stage set and microphones are themselves animated performers.) Ten are at the Hammer, five at ICA L.A.

Among the more compelling works are Lara Schnitger’s monumental fashion icons — giant, literal stick figures dressed to the hilt from scraps of snazzy jersey, lace, vinyl and feathers, making more than something from less than nothing. (Think an outfitted R. Crumb cartoon marching into the Met Gala.) A room-divider sculpture by Leonor Antunes reimagines the underrecognized midcentury work of L.A. architect and designer Greta Magnusson-Grossman, turning domestic crafts like weaving and leatherwork into political commentary.

In a similar ballpark, Laura Lima has set up a professional sewing room inside a gallery. Two talented tailors — Lily Abbitt and Surjalo — produce garments that are then stretched and framed like abstract paintings. “Steel to Rust – Meltdown,” a gorgeous abstract painting by Otobong Nkanga, turns out to be an exquisite tapestry, its broad landscape view at once luminously aerial and darkly subterranean, all shot through with metallic threads.

Tiny portraits on scrap paper by performance artist Vaginal Davis celebrate women who are personal idols, ranging from her mother to pioneering L.A. art dealer Margo Leavin, who died last month. Davis, like the legendary San Francisco artist Jerome Caja (1958-1995), paints with eye shadow, lipstick and other messy cosmetics — Aqua Net hairspray fixes the fragile surfaces — which makes them generalized acts of homage more than acute physical likenesses.

Beverly Semmes piles up hand-formed clay pots, each glazed ruby red, forming raging phallic towers. The traditionally feminine associations of a vessel are slyly discomfited by dense tangles of handles, Medusa-like in their clusters of writhing, snakelike forms.

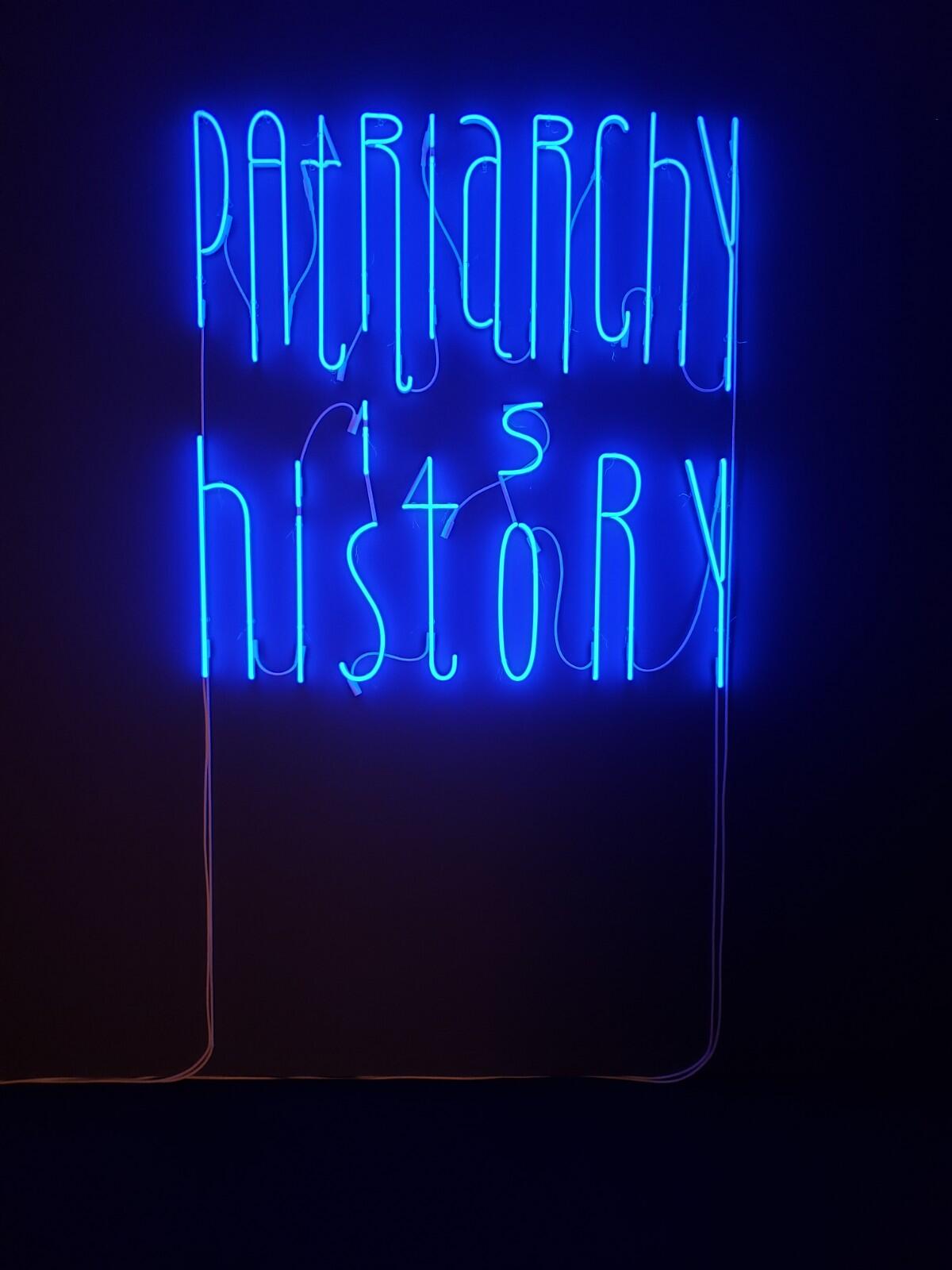

Ancient Greeks invented Medusa to be an evil female image who would ward off other evils, and Semmes’ complex sculptures are likewise enlivened by paradox. Another double-edge point is made in what could be a “Witch Hunt” exhibition motto: Wall script in blue neon by Yael Bartana coolly announces, “Patriarchy is history.”

The past is described — and simultaneously tossed into the dustbin.

Many scholars think the mass hysteria of the Salem witch hunt was fueled by a local Protestant patriarchy, who regarded witchcraft as a supernatural affront to biblical practice. Under the town fathers’ failed leadership in the face of survival setbacks in 1692 Salem, the feverish trials functioned as a useful diversion.

Pretty much the same could be said about Trump, who needs a Bible-thumping witch hunt to keep his white fundamentalist Christian base whipped up. But one man’s supposed persecution as a witch faces a diverse array of women’s insistent liberation demands, as this exhibition happily asserts.

'Witch Hunt'

UCLA Hammer Museum. 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood, (310) 443-7000. Closed Mon.

ICA L.A. 1717 E. 7th St., (213) 928-0833. Closed Mon. and Tue.

Both through Jan. 9.

A selection of Edmonds’ paintings and works on paper created over four decades is now on view at Loyola Marymount’s Laband Art Gallery.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.