L.A.’s memorial for 1871 Chinese Massacre will mark a shift in how we honor history

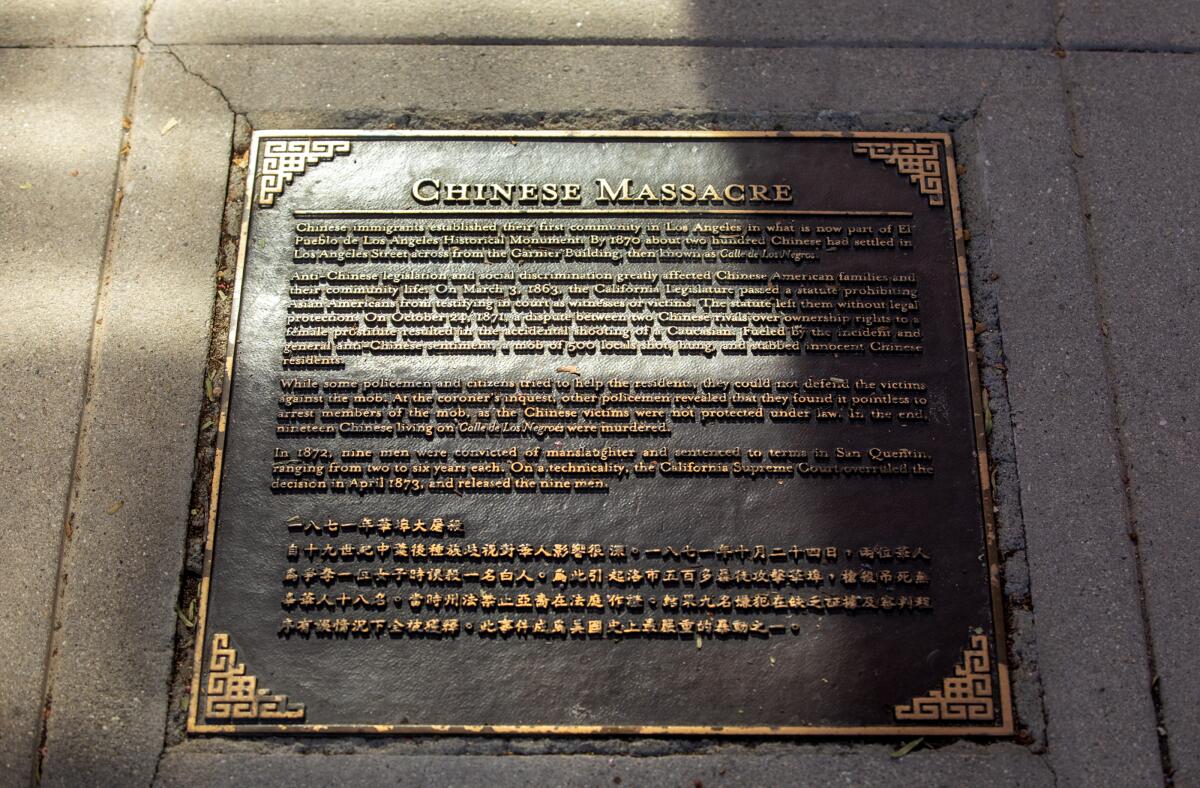

The plaque marking the Chinese Massacre of 1871 is not easy to find.

Embedded into the sidewalk on North Los Angeles Street in front of the Chinese American Museum downtown, it is one of several bronze markers the museum installed in 2001 to commemorate key moments of Chinese American history in L.A. English and Chinese text is piled into a square smaller than a pizza box, which requires you to stoop over awkwardly to make out the words. I’ve walked over it dozens of times without noticing it.

Its humble proportions belie the plaque’s significance as a rare civic acknowledgment of one of L.A.’s most shameful episodes: the spasm of violence that took place on Oct. 24, 1871, when a mob brutally murdered 18 Chinese men — an estimated 9% of L.A.’s Chinese population — at a time when the city barely registered 5,700 people.

Soon, this important history will no longer get lost underfoot.

On Friday, the 1871 Steering Committee, a team of civic and cultural leaders coordinating with the city’s Civic Memory Working Group, impaneled by Mayor Eric Garcetti to study L.A.’s monuments, is set to release a report with recommendations for a proper memorial to the massacre. It features assessments of possible locations, which include the broad sidewalk in front of the Chinese American Museum — an area where much of the violence took place.

The city has put $250,000 toward getting the project off the ground. And, early next year, the mayor’s office, the Department of Cultural Affairs and the office of Councilmember Kevin de León, in whose district the sites related to the massacre all lie, will come together to issue a “Request for Ideas” — a public process that will allow designers to propose general concepts for how such a monument might be sited and built.

The 1871 Steering Committee was chaired by Michael Woo, the first Asian American to be elected to the Los Angeles City Council and a former dean at Cal Poly Pomona; and Gay Yuen, board chair of the Friends of the Chinese American Museum. Other co-chairs include Jessica Caloza, a public works commissioner; David Louie, vice president of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument Commission; and Felicia Filer, director of public art at the Department of Cultural Affairs. On Friday evening, Woo and Caloza will appear on a virtual panel organized by the Chinese American Museum to discuss the memorial.

All of this lands at a critical time.

For one, this year marks the 150th anniversary of the Chinese Massacre and coincides with a rise in anti-Asian incidents across the U.S. instigated by anti-Chinese political rhetoric related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, it is a moment in which the nature and subject of civic monuments are in question, with burgeoning scholarship investigating the role monuments play, as well as the histories they record or, conversely, fail to capture entirely.

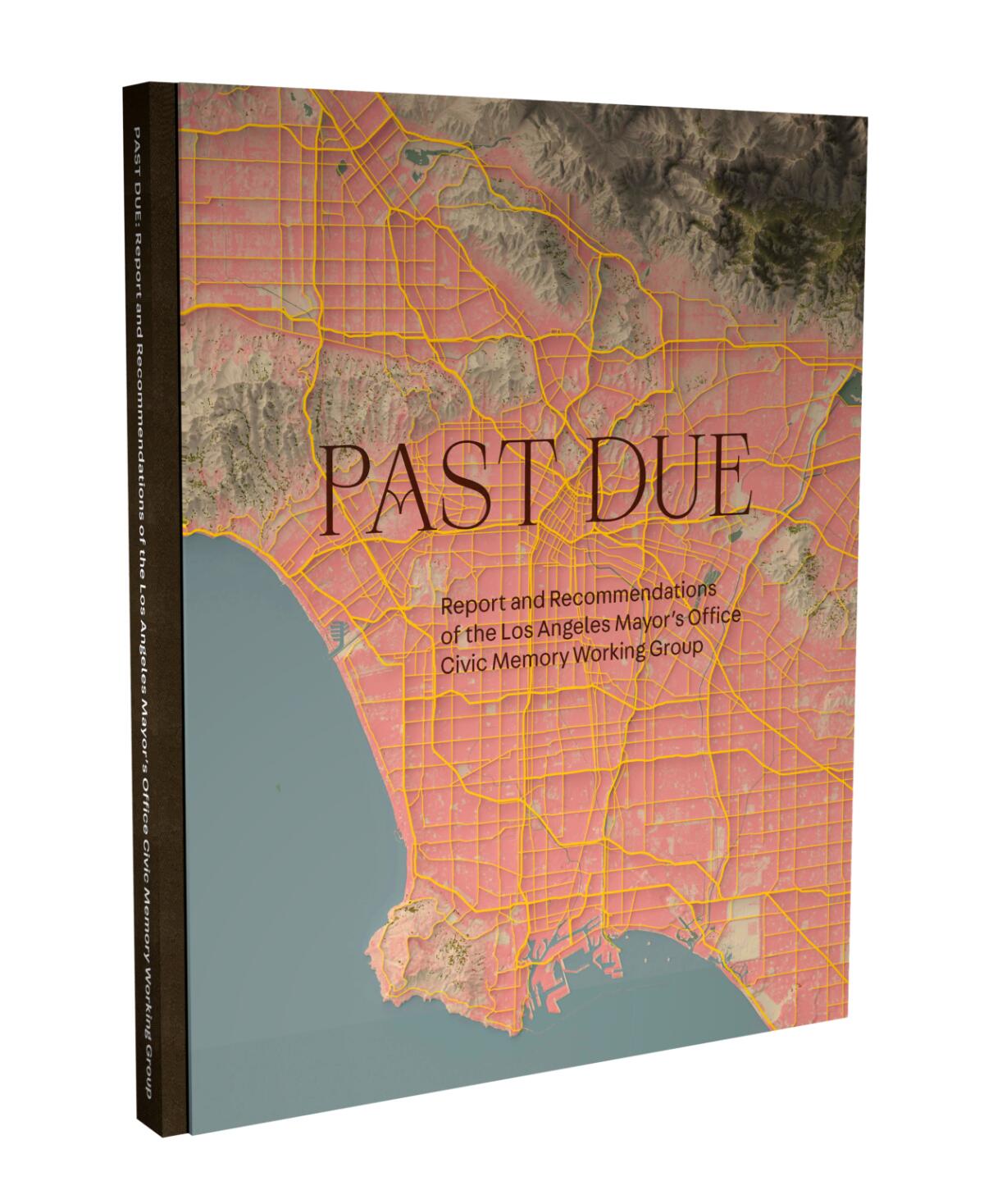

In April, the Civic Memory Working Group — more than 60 Los Angeles historians, writers, curators and Indigenous elders led by the city’s chief design officer, Christopher Hawthorne — published “Past Due,” an in-depth report focused on Los Angeles monuments. It offers recommendations on matters including making the monument design process more democratic and suggesting that the city undertake a comprehensive audit of its monuments and memorials.

L.A. has a long history of anti-Asian sentiment. In 1871, a mob attacked Chinese people, killing 19, including a 14-year-old boy and a physician.

It also offers some genuinely enjoyable reading, including essays by a diverse range of cultural figures, including D.J. Waldie, Mike Davis, Guadalupe Rosales, John Rechy and Sam Sweet. “For all the blink-and-it’s-gone sleights of hand,” writes essayist Lynell George in one such section, “here in Los Angeles, the deep past can catch you unawares.”

“Past Due” was followed last month by a report from Monument Lab, a nonprofit Philadelphia studio that studies monuments and facilitates discussions around them. Its “National Monument Audit” compiled 42 data sources, bringing together some 500,000 individual records, to produce an analysis on popular monument types across the United States.

War, as expected, is a more popular subject than peace, and of the top 50 individuals recorded in public monuments nationally, only three women made the list: Joan of Arc, Harriet Tubman and Sacagawea. The audit also notes that there are more recorded monuments to mermaids (22) than to U.S. congresswomen (2).

As part of its study, Monument Lab created a free online database that allows the public to filter monument data by keyword, geography or type (say, a statue versus a bas relief). The database is by no means a complete accounting of every monument in the United States. The researchers were limited to whatever was archived on existing databases, which are often incomplete. And for the purposes of their project, they focused on sites and structures “we most conventionally think of as monuments,” including statues or monoliths “installed or maintained in a public space with the authority of a government agency or institution.”

But the extensive data they did gather paints an interesting picture. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee emerges as the sixth most popular individual recorded in their public monuments database, with other Confederate leaders, such as Stonewall Jackson and Jefferson Davis, ranking among the top 15. For the record, Abraham Lincoln is No. 1.

Taken together, the two reports tell an interesting story about how the methods by which communities erect monuments is changing and where the gaps in representation lie — both around the nation, but also in California specifically.

Take the case of Junípero Serra, the controversial 18th century Franciscan friar who served as architect of California’s mission system.

The friar came in at No. 27 among Monument Lab’s national top 50. In addition to copious representation in California, statues of Serra appear in Florida and Arizona. He also materializes in places that the databases don’t account for, such as inside the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, where a statue of Serra represents California alongside one of Ronald Reagan. That’s right — California, a state named for Calafia, a Black warrior queen of 16th century Spanish chivalric literature, is represented by a couple of dudes.

Shouldn’t public monuments have public input? In the George Floyd moment, artists and designers are changing the nature of monuments and the histories they honor.

Conversely, when it comes to memorializations of Indigenous people, the representations are often ersatz, generic or difficult to find. Monuments of Indigenous figures rarely note tribal affiliation or other culturally specific markers, instead functioning as representations of Native everymen in larger narratives about settlement. When actual historical figures are rendered, the circumstances can leave something to be desired. Near Lincoln Park in Los Angeles, a statue of Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec emperor, lords over an awkwardly shaped traffic island — sponsored, in part, by the Cervecería Cuauhtémoc Moctezuma, a Mexican beer company.

More thoughtful monuments to the Native experience in Los Angeles do exist — such as the Tongva Memorial located on a bluff at Loyola Marymount University — but it’s tucked away on a private university campus.

‘Biddy’ Mason? Jackie Robinson? Cesar Chavez? Linus Pauling? California’s history is filled with figures of greatness who could represent us well in Washington’s statuary collection.

To try to understand California history through its monuments is to come away with a highly skewed vision of historical events. Through statues, we learn the story of Serra, the great evangelizer, who brought Christianity to California. The story of the region’s Indigenous inhabitants, however, is muted.

It, therefore, comes as little surprise that of the 18 recommendations issued by the Civic Memory Working Group, three are focused on better recognizing Indigenous history in L.A.

In this regard, Chinese Americans suffer from similar oversights.

Combing through the Monument Lab database, I found numerous monuments, plaques and markers around California (especially in the Sierra) that pay broad tribute to unnamed Chinese laborers who helped build railroads, including one oversized sculpture with the uncomfortable title of “The Chinese Coolie.” It’s harder, however, to find acknowledgment of the achievements of Chinese American individuals, or more complicated narratives around the episodes of anti-Chinese racism that racked the state in the second half of the 19th century.

The Chinese Massacre of 1871 didn’t come out of nowhere. At the time, Chinese people were forbidden from owning property, marrying white people and were denied equal legal protection. This culminated in 1882 with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, a federal law that prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers to the United States. During that era, Los Angeles was not the only site of violence. In 1887, arsonists in San Jose torched that city’s Chinatown, an act for which city officials formally apologized last month. (The event had previously been commemorated, in 1987, by a plaque.)

On the whole, however, California’s monuments largely leave out the more difficult parts of the Chinese American story.

The designer of Washington, D.C.’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial is shaping the way women learn at Smith College and with ‘Ghost Forest’ makes a climate change statement.

Both of the monument reports ultimately call for a more flexible approach to monument building — such as installations that can be adapted over time.

Monument Lab notes that Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington has had 342 names added or changed since it was installed in 1982. And the Boston monument to the 54th Regiment, the first Black unit in the Union Army during the Civil War, didn’t have the names of the Black soldiers inscribed until the 1980s — almost a century after it was installed.

Adaptability might mean contextualizing old monuments with additional signage or simply creating monuments that are more ephemeral in nature. As the “Past Due” report states: “Might we embrace or invite or encourage ephemeral commemorations that do not have the ‘fixed’ problem built in and that do not unduly fetishize permanence?”

One recommendation is to create memorials that might take the form of gardens, a type of monument that would be highly functional in park-poor Los Angeles (provided they are maintained). Murals, which can be relatively easily installed and repainted, are also discussed — unfortunately, only cursorily.

Murals have a long and complicated history in Southern California. For a time in the early 2000s, they were banned in L.A., and El Monte only just lifted its 45-year moratorium on the form. But muralism has a long track record of representing histories that often go untold in our official monument landscape.

Judy Baca’s “The Great Wall of Los Angeles,” created in the 1970s, is a half-mile-long mural in the Tujunga Wash Flood Control Channel in North Hollywood that tells the history of California from prehistory to the present. It has representations of Indigenous labor in the Spanish missions and a panel about the Chinese Massacre, not to mention sections on the Japanese American wartime incarceration and the Zoot Suit riots. (It is currently the subject of a compelling video installation on view at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach as part of a retrospective devoted to the artist.)

“The Great Wall of Los Angeles” is on the National Register of Historic Places, yet it doesn’t appear in monument databases. All the overlooked and erased histories we are discussing now? Baca and her collaborators were painting them back in the 1970s.

It’s time to be more imaginative about what constitutes a monument.

“Past Due” is essential reading for reimagining the ways by which monuments get built. Historically, an organization might gift a monument to the city or one would be commissioned by a government entity, its production left in the hands of a tiny jury. In these cases, the public often has little say in site selection or the design process. The report urges the city to scrap this model and evolve its role “from gatekeeper to resource,” serving not as authority but as a facilitator.

And that’s exactly how the monument to the Chinese Massacre is being conceived.

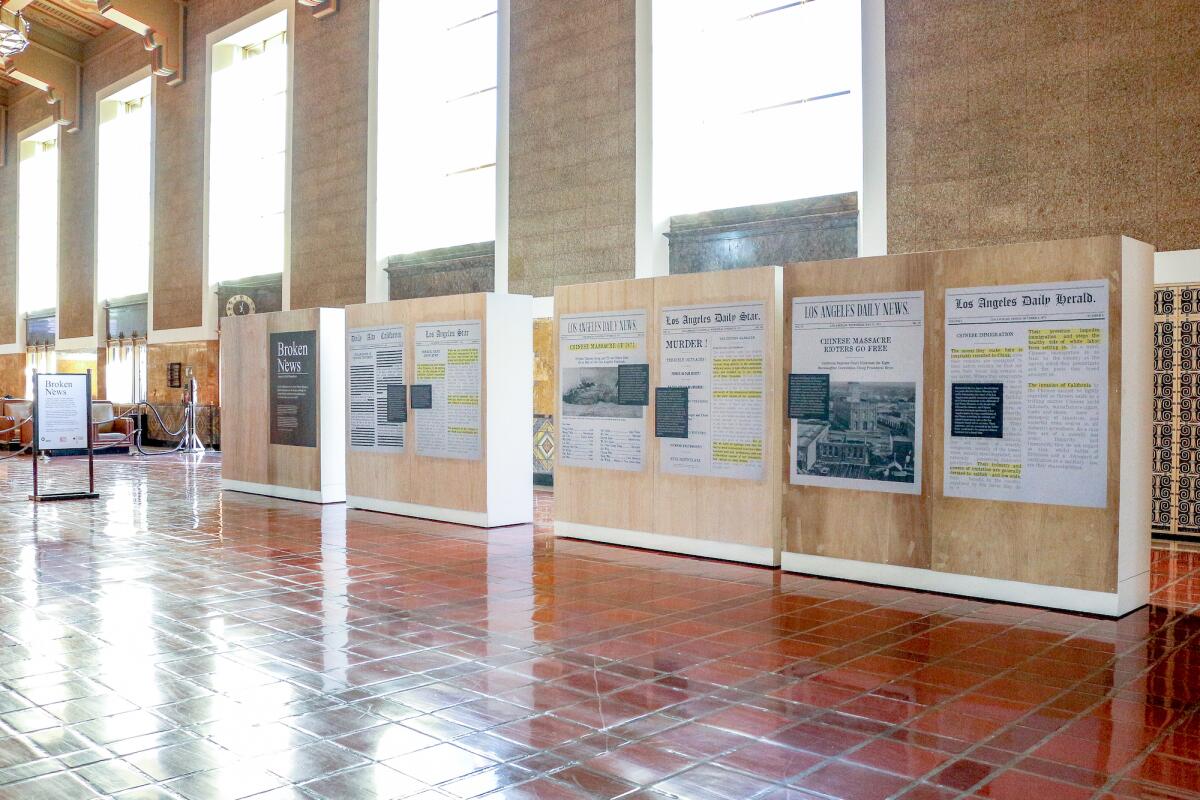

The 1871 Steering Committee investigated locations but lists them only as suggestions. Its members have produced public forums on the subject to invite community participation and have led walking tours of potential sites. Artist Adit Dhanushkodi, in collaboration with cultural organizer Rosten Woo and historian Eugene Moy, has created an installation titled “Broken News,” currently on view at Union Station, which investigates anti-Chinese sentiment in the Los Angeles press in the late 19th century.

As a next step, the steering committee has advocated for a broad “Request for Ideas” rather than a more specific “Request for Proposals,” so that smaller design firms won’t be disadvantaged by larger studios who can produce splashy renderings. From that idea pool, organizers will select a shortlist that will be given a stipend to produce designs — a way of limiting unpaid labor on the project.

On Sunday, to mark the 150th anniversary of the Chinese Massacre — the largest mass killing of any kind in Los Angeles history — the Chinese American Museum is organizing a commemoration in which the victims’ names will be read and a wreath laid. Mayor Garcetti and other officials will be in attendance.

This year that commemoration comes with a promise that the deaths of those 18 Chinese men will be recognized within the fabric of our city. But not in the old way, by simply plunking a statue into some random square. Instead, it will be about coming together as a city, in all the ways that never happened while they were alive.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.