Commentary: ‘The Music Man’ is the wrong Broadway revival for this crucial moment

Days after Scott Rudin announced he was “stepping back” from his various projects due to allegations of abusive behavior toward his staff, Hugh Jackman assured media that the team behind his Broadway production of “The Music Man” was “rebuilding” without the producer. The starry revival — also with Tony winners Sutton Foster, Jefferson Mays and Jayne Houdyshell — is now set to begin performances in December, more than a year later than initially planned.

“‘The Music Man’ is a joyous love letter to the United States and a celebration of what we can achieve when we come together,” said Kate Horton, the executive producer replacing Rudin. “We will ensure our team enjoy the right conditions for creating their most brilliant work and sharing it with the widest possible audience.”

As Broadway celebrates its return after a historic pandemic closure, offerings like this one beg the question: What exactly are we welcoming back? Why make such great attempts to salvage this particular project in the first place? Upon further analysis, it seems quite a choice to prioritize “The Music Man” in 2021.

To start, “The Music Man” is Professor Harold Hill, a traveling salesman who sells a small Iowa town on the urgent need for a marching band. He does this by, first, scaring parents with the looming threat that their children could be corrupted, and then pitching them a solution to prevent this exact fate.

The studios, already lacking diversity, expect high-profile films with nonwhite casts to be “proof of concept.” All it creates is unfair pressure.

It doesn’t matter that Hill knows absolutely nothing about playing music, let alone teaching it; he is so charismatic and charming that his “think system” for such a skill — “If you want to play the ‘Minuet in G,’ think the ‘Minuet in G,’” he claims — seems sound enough.

The locals buy in — they get to protect their youth and enjoy live performances, a win-win indeed — and pay Hill, who plans to leave town just before any of the uniforms and instruments arrive, as he’s done in many, many places before this one. (Yep, this “feel-good romantic comedy” is a scammer story!)

The only person who doesn’t fall for Hill’s scheme is Marian, the well-read woman who is entirely defined by her unmarried status and ends up falling for Hill. He ultimately realizes the error of his ways, as Marian “transforms him into a respectable citizen by curtain’s fall,” reads the show’s licensing page.

“Essentially, Hill’s gimmick is selling small-town hicks on high culture and the idea of self-improvement: using their own American idealism as the very bait that turns them into his marks,” wrote Dan Venning in the Journal of American Drama and Theatre. He cited “The Music Man” as one of numerous musicals that centers on, and ultimately romanticizes, a scammer, just as in “The Producers,” “The Book of Mormon,” “Dirty Rotten Scoundrels,” “Dear Evan Hansen” and more.

“Musical con artists embody an extreme lionization of American individualism,” Venning wrote, “becoming emblematic of the ways in which our culture wants to understand, forgive, or even idolize those who take advantage of others, precisely because grifters maintain their status as empathetic subjects, even — or perhaps especially — as they turn people and communities into objectified marks.”

At its best, “The Music Man” can capture “the fragile but glorious potential of American optimism; our nation’s ubiquitous eccentric imperfections; the transformative power of the arts in education,” wrote Chris Jones in the Chicago Tribune.

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ celebrated ‘An Octoroon’ has its Los Angeles premiere at the Fountain Theatre’s new outdoor stage.

But its agreeability still depends on whether audiences can excuse Hill’s ruse, enjoy his entertainment, become as enamored as Marian, root for their romance, pardon his career of lies and swindles, then consider his rebirth as authentic. (If anyone can distract viewers from a con with charm, it’s probably Jackman, who has long hoped to play Harold Hill and portrayed men of questionable ethics in the movies “The Greatest Showman,” “The Front Runner” and “Bad Education.”)

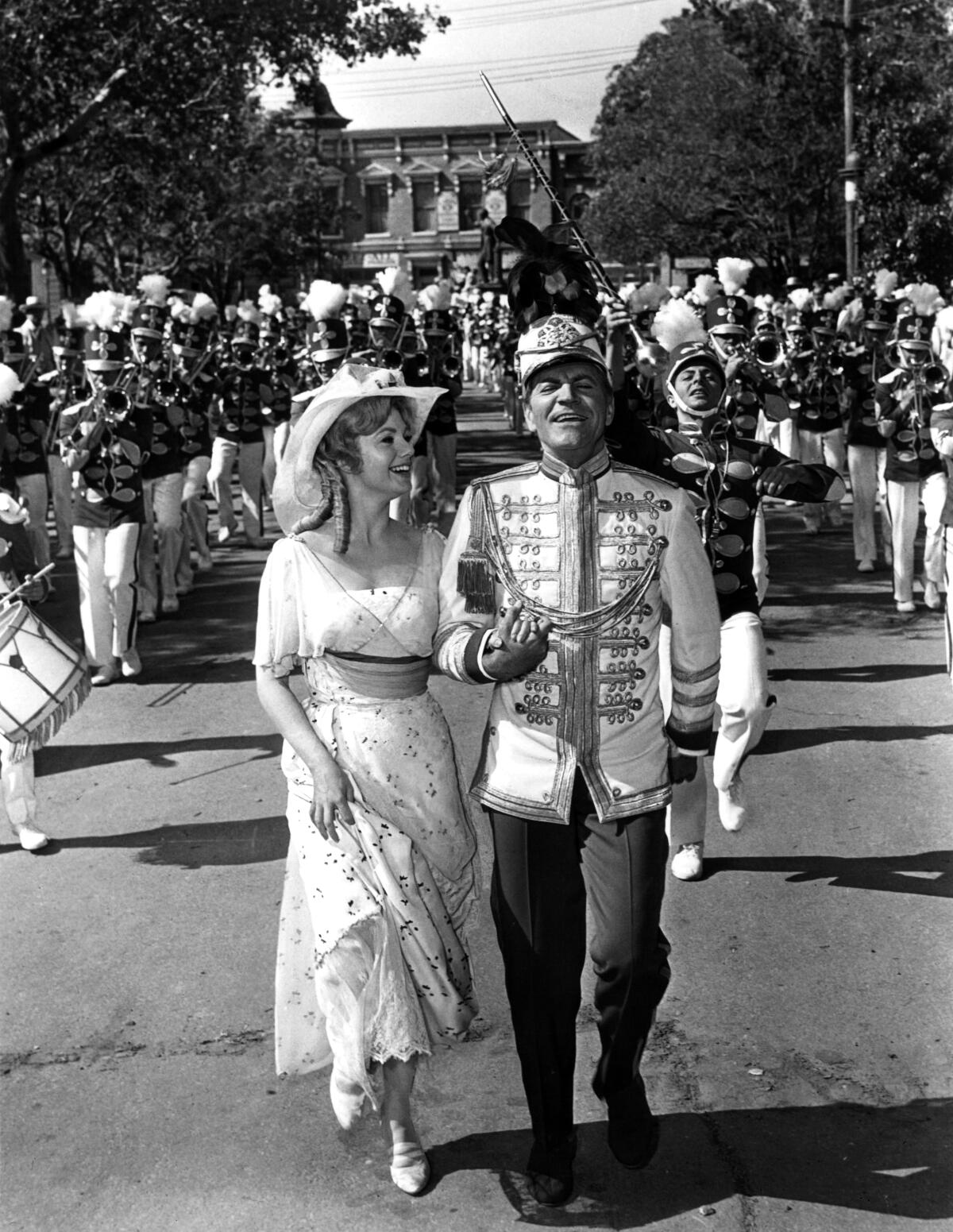

Theatregoers were game when “The Music Man’’ debuted on Broadway in 1957. It ran for 1,375 performances and won five Tony Awards, most (in)famously winning best musical over “West Side Story.” Its recording won the first-ever Grammy Award for original cast album. And it was adapted into a beloved 1962 movie (which won an Oscar for its score of fast-talking songs and sweeping ballads) and a 2003 television movie.

It remains a popular pick among regional professional theaters and school theaters (who then must consider the story’s racist scene toward Native Americans), thanks to its entertaining songs, large cast allowance and accessibility. “[It] sells a version of culture that is neither ‘high’ nor ‘low,’ but lucrative in its averageness and uniquely American in its easy reconciliation of diametrically opposed notions of art and commerce, patriotism and individualism, truth and scam,” Kimberly Faithbroker Caton wrote in Modern Drama.

Though Meredith Willson wrote its music, lyrics and book by pulling from his own childhood — “I simply remembered Iowa as closely as I could the way it was,” he told The Times in 1979 — “The Music Man” initially drew, and has maintained, acclaim in part for its specific depiction of small-town America.

“The show is frankly a happy valentine to yesterday, rich with music and laughter and the sentimentality of a less-complicated world,” wrote L.A. Times entertainment editor Cecil Smith, just before a production opened in Los Angeles in 1958.

“It was another, more peaceful time and place, this year of 1912 in the horse-and-buggy Middle West — an America easier to know and understand and love, for all its quaintness and ‘hick’ innocence,” echoed Los Angeles Times film critic Philip K. Scheuer of the 1962 movie.

“The Music Man” is perhaps “the most American American musical of them all,” wrote The Times’ entertainment editor Charles Champlin in 1984. “If you had called someplace like River City home, you knew how well Prof. Willson had captured a part of your past, as well as his own, creating memories of the way it ought to have been.”

Michael Ritchie is stepping down as artistic director of L.A.’s most important theater company. What can his replacement — or replacements — do differently?

The show’s rose-colored representation of Willson’s hometown is arguably expected, as “The Music Man” is rooted in his childhood memories. And these printed descriptions are likely accurate to those who wrote them; like the American theater, journalism is an industry historically dominated by white people.

Yet these sentences are full of coded language about the show’s sanitized and idealized setting, and its intrinsic value as a quintessential America. In reality, River City is probably as much a sampling of America as the Iowa caucuses are of presidential races: “The first-in-the-nation caucus state is whiter and more rural than the rest of the country; it doesn’t really represent America in some fundamental ways,” said NPR’s Sam Sanders. (The show’s nostalgia for a certain whiteness is in the text itself and can’t be easily solved with casting.)

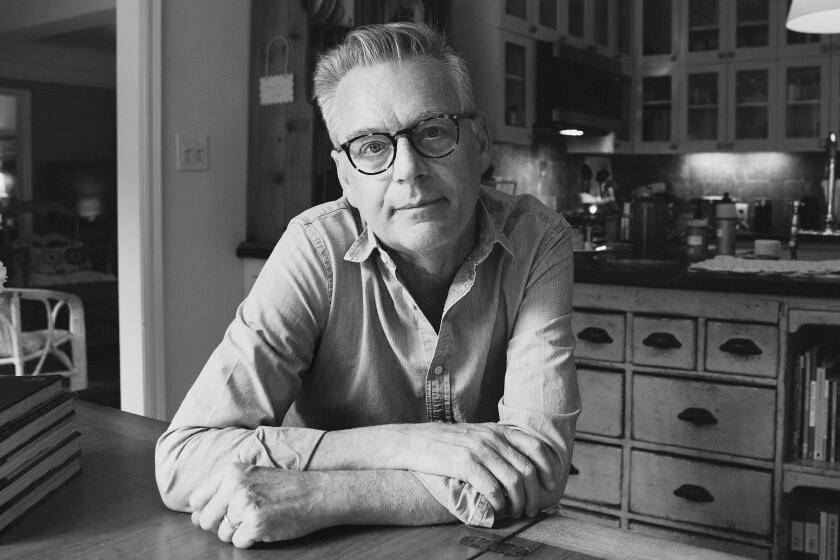

I’m not calling for “The Music Man” to be canceled. I actually had a fine enough time revisiting its various cast albums, screen adaptations and archival footage to write this piece; Robert Preston, who originated the role on Broadway and reprised his performance in the 1962 movies, remains as magnetic as ever. And I’m sure that the revival’s rendition of “Seventy-Six Trombones,” as directed by Jerry Zaks, will be an unforgettable spectacle, especially with Jackman in his first Broadway musical role since his debut in “The Boy From Oz” nearly 20 years ago.

The problem arises when this fantasy is mounted as an upbeat, tidy time capsule, allowing audiences to ogle a version of America that never existed. Ultimately, “The Music Man” sets forth a sanitized, insular and very white America — a vision regularly exploited by a recent president (who gained a following with scare tactics and sold a “think system” of his own) to stoke racial fears and pit Americans against one another. It asks audiences to cheer for yet another romanticized fraud.

“The Music Man” is selling tickets while the culture is calling for corrective lenses on such white-centered visions of American history and protesting in the streets for a new vision of modern American life. The same is true of the theater industry itself, as actors and arts workers marched for a more inclusive, equitable and anti-racist workplace.

It is highly unlikely that this revival will question its source material, as Daniel Fish’s “Oklahoma!” did; most recent restagings of “classics” instead attempt to reframe problematic plots as updates. Not that every Broadway offering needs to address real-world issues, but it’s concerning when productions not only turn away from society’s exposed ills but also inherently reinforce them for, as Horton said, “the widest possible audience.” In the words of Harold Hill himself, it’s “trouble with a capital T.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.