Why the end of Flash animation marks the end of an era for creativity on the web

It was a tale of sex and death and Teletubbies.

In 1998, programmer and animator Tom Fulp released an online video game titled “Teletubby Fun Land” that featured the characters from the British children’s television program getting drunk and stoned and engaged in acts of devil worship. One of the game’s narratives showed a version of Po (the red one) getting it on with a sheep.

As the site grew in popularity, the BBC, which aired “Teletubbies,” grew appalled. In 1999, the British broadcaster demanded that Fulp, then a college student, take the site down. He initially acquiesced, but within days, “Teletubby Fun Land” was right back up — with Fulp noting that parody was protected under laws governing free speech.

“As far as I have always known, Mad magazine makes a living out of doing the same thing,” Fulp told Wired at the time. “I am pretty sure U.S. laws protect me.”

Since then, the game has remained online, making it possible to return to the internet of 1998, where you can blast parodic Teletubbies into bloody bits.

“Teletubby Fun Land,” however, could now be headed for extinction.

On Dec. 31, Adobe will no longer support Flash, the animation plug-in that allows the game to function. Unless it is recoded using another program, it will become impossible for most web users to access it. Already, browsers such as Safari do not support Flash technology, making it impossible to even view the game’s start screen on that platform. By the end of this year, Firefox and Chrome will also remove Flash from their browsers.

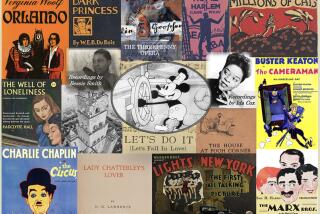

This spells the likely end not just for Fulp’s demented Teletubbies but also for a range of creative works that were generated using Flash and that still exist in that form. The formal end of Flash also functions as an important marker in the internet’s transition from the creative free-for-all of the ’90s, with its GeoCities homepages and weirdo chat rooms, to the corporatized space of today, dominated by a handful of U.S.-based technology companies that tech writer Farhad Manjoo describes as “the Frightful Five.”

“Flash disappearing can be seen as a marker of that,” says Ben Fino-Radin, an art conservator and entrepreneur whose New York City firm, Small Data Industries, helps preserve works that may have been produced on now outmoded technologies. “Even though [Flash] was a proprietary technology, its accessibility marked this era of oddball creativity.”

And oddball is right.

There was Zombo.com, a satirical site from 1999 that made fun of websites that took too long to load because they were overloaded with Flash animations — by creating a website that never loads using Flash animation.

The popular “Badger Badger Badger,” a 2003 meme created by British animator Jonti Picking, shows a troupe of dancing badgers and a very large mushroom as a guy chants, “Badger, badger, badger, mushroom, mushroom.” (Thankfully, these absurdist and downright hypnotic pieces will not disappear: An HTML version of Zombo.com is now in existence, and “Badger” can be streamed on YouTube.)

Certainly, Flash was never intended to just supply raw materials for stoned Teletubbies and dancing badgers.

The program got its start in the mid-1990s as FutureSplash Animator before being acquired by Macromedia. For a time, as Richard C. Moss notes in a thorough (and entertaining) history of the program published on Ars Technica in July, it reigned supreme.

Soon, Flash was absolutely necessary to view countless internet sites. In 2005, it was acquired by Adobe. Shortly thereafter, it became the de facto player for a burgeoning video sharing service called YouTube — and remained so until 2015. Flash animations were used on U.S. Air Force recruitment sites and by architects trying to look fancy (to the irritation of, well, anyone who actually wanted to locate information).

But technical issues (the software didn’t work equally well on all browsers) and leaky security (it became a target for viruses and malware) began to hamper its use. In 2010, Apple Chief Executive Steve Jobs announced that he would not allow Flash-derived applications on iPhone or iPad.

Since then, its use has plummeted: About 80% of desktop Chrome users made daily visits to a site that employed Flash in 2014, according to a 2017 blog post by a Google product manager. Three years later, that figure had fallen to 17%.

Plus, the browsers that continue to support it do not make it easy to use. On Chrome, users have long had to enable the plug-in every time they landed on a page that contained Flash.

During its brief and wondrous life, however, Flash became attractive to a generation of visual artists interested in turning the internet into a virtual canvas. That movement, with its roots in ‘90s internet culture, is generally known as net art or net.art.

“It’s as if the light is being turned off on a piece of the internet. It will be still there, but it will sit in the dark.”

— Carolina A. Miranda

Early innovators such as Rafaël Rozendaal, for example, used Flash to create one-off websites, each of which functioned as a singular work of art — such as the 2007 piece “Future Physics,” in which the viewer could bounce planets off one another in space. (The piece still requires Flash to function, though you can read about it on the website of the Electronic Language International Festival, known as FILE.)

Others, like the now-defunct collective Paper Rad, used the program to create absurdist psychedelic cartoons that embraced pixelated graphics and highlighted the lo-fi qualities of sound. (One of Flash’s defining features was the way in which it compressed audio, making it tinny.)

Like many materials, says Fino-Radin, the program was employed by artists because it was relatively cheap and simple to use.

“You could do rich interactivity and create narrative experiences in an affordable and accessible format,” he says. “Whereas, previously, you would have had to do that on LaserDisc.”

Young-Hae Chang and Marc Voge, a Seoul-based duo that goes by the moniker Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, is known for creating poetic text-based pieces that seize a viewer’s screen and are set to a score. Their early animations were produced in Flash, including the 2008 piece, “PLEASE COME PLAY WITH ME, BABY / PLEASE DON’T THANK ME,” which was shown at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2009, in the group exhibition “Your Bright Future: Twelve Contemporary Artists From Korea.”

“We started to use Flash, because an art center gave us a free copy of Macromedia Flash,” they state via email from South Korea.

“Flash was good to us. We learned to use our little bit of it in an hour so. ...The little we learned of Flash was enough for us to become Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries.”

As Flash has faded, however, the pair have switched to other technologies. They now present their work online in streaming video formats instead.

Artists who converted other cruder technologies into Flash now face the task of upgrading again. That’s the case, as reported by Isabel Ochoa Gold in Criterion, of the 1997 CD-ROM project “Immemory” by the late French filmmaker Chris Marker. The game-like memoir had nearly disappeared on its increasingly useless CD-ROMs in 2011 when the Centre Georges Pompidou converted “Immemory” into a Flash experience — which will become obsolete on Dec. 31. Galaxie 500 musicians Damon Krukowski and Naomi Yang, who worked with Marker to create the English-language CD-ROM, hope to transfer “Immemory” into a book edition; a YouTube play-through version exists, but Marker’s vision of an interactive journey will soon be gone.

“At some point,” Ochoa Gold writes, “love and attention are not quite enough to preserve digital media as it was and keep it accessible.”

Still, says Fino-Radin, who before establishing his own firm worked as a conservator at New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art and the Museum of Modern Art, Flash works will continue to exist. It will simply become infinitely more difficult to see them.

“The bits are still there. The bitstream files will still exist,” he says. “But our ability to access them or render them is becoming much more difficult.”

It’s as if the light were being turned off on a piece of the internet. It will be still there, but it will sit in the dark — accessible only to those hardcore enough to hold on to vintage hardware and software, or those who employ programs called emulators that can mimic the functions of old software on new machines. (Archive.org, which features a range of emulators that allow devoted gamers to resuscitate vintage video game programs. now hosts a Flash emulator.)

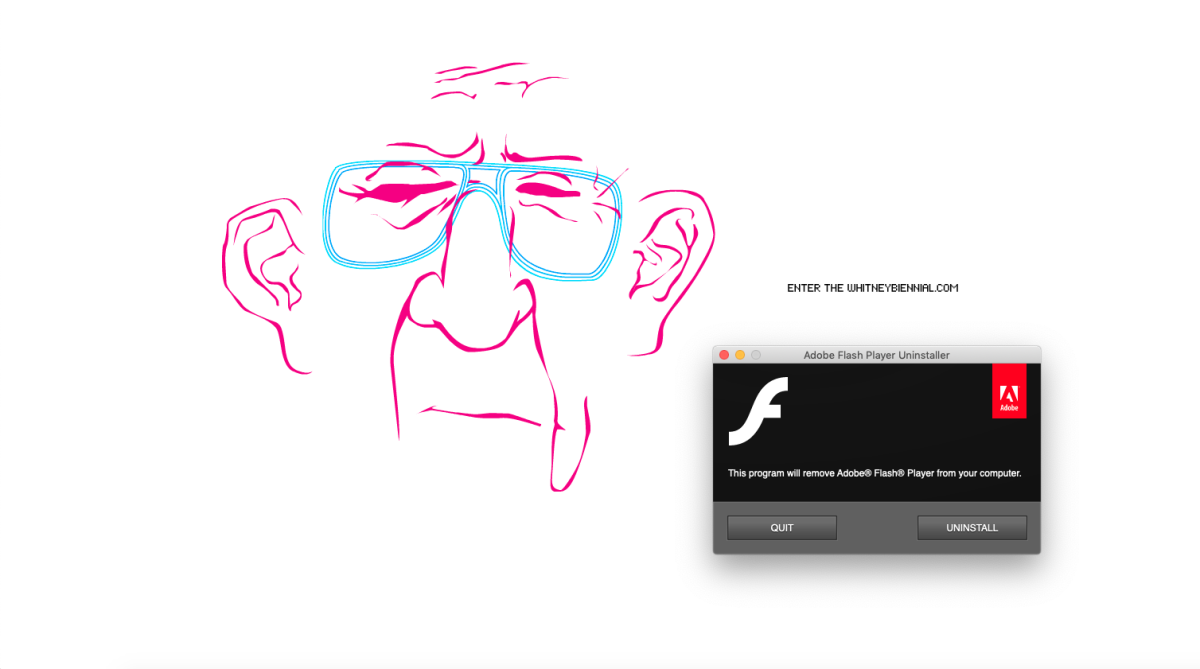

In 2002, artist Miltos Manetas, who was then based in Los Angeles (he helped establish the now defunct Chinatown art space electronicOrphanage), acquired the URL whitneybiennial.com and used it to stage a guerrilla exhibition of virtual works with a group of fellow artists. This cheeky display had nothing to do with the prominent biennial organized by the Whitney Museum in New York. (Lucas Pinheiro at Rhizome has a good story on its genesis and inspirations.)

Whitneybiennial.com involved the work of dozens of artists, designers and architects — including Rozendaal and Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, as well as now-prominent artists such as Leo Villareal and Rainer Ganahl and the graphic design team Experimental Jetset.

“All that the artists had to do was a Flash animation, it didn’t have to be any complicate[d] conceptual work,” Manetas wrote of the project in 2003, “a cute moving-image would be OK.”

New and old versions of the site still exist, much of it still coded in Flash — which means that time is running out to see pieces of this biennial cybersquat unless it gets fully upgraded.

Flash was not the only iconic program of the era (GIFs were already in existence). But as Lev Manovich wrote in “Generation Flash,” an essay that was published in conjunction with the whitneybiennial.com show, “Flash aesthetics” embodied a cultural sensibility.

To me, these aesthetics mark a time when the internet felt fresh and subversive, when artists built their own systems rather than inhabit the corporate social media platforms of others, when the internet felt like community rather than algorithmic churn.

At a time when we are tethered to the internet in an endless doom scroll, it’s impossible to fully return to that state of early idealism. But in the days that Flash has left, it is possible to catch a glimpse of it — before it is gone.

Not quite as mysteriously as a monolith, a website has appeared for a fictional Donald J. Trump Presidential Library. The anonymous architect tells us why they did it.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.