How do you get people to stop believing the lies? Ask artist Alison Jackson

Alison Jackson was a graduate student at London’s Royal College of Art when Princess Diana died in 1997. The intensity of the nation’s grief fascinated — and rankled — her.

“Diana was so present in our lives, like a member of our family,” Jackson recalled. “The press made us feel very close to her, but in fact she was very distanced from us.”

Jackson turned to photography to address that phenomenon of presumed intimacy with the famous. She started making pictures visualizing what thrived and lurked in the collective imagination, tightly crafted fictional scenes using convincing look-alike models. In one, Diana smiles devilishly as she flips off the camera. In another, the most incendiary of Jackson’s initial batch of contrived stills, Diana and boyfriend Dodi Fayed strike elegant, informal poses on either side of a baby, ostensibly theirs.

The media went wild, condemning Jackson’s work but reprinting the fabricated visions in exactly the same spots reserved for news. She has continued to traverse the inexhaustible territory of celebrity obsession and media manipulation, creating pictures so persuasive that viewers have insisted that she really did catch Queen Elizabeth II extracting cash from an ATM, Kanye packing Kim’s rump into her Spanx, or Donald Trump consorting with hooded Klansmen, even when Jackson insists right back that it’s all a matter of elaborate theater.

Jackson, who is based in London and also active in television, film and advertising, is having her first L.A. show since 2007 at the work and event space NeueHouse Hollywood through Dec. 18. “Truth Is Dead” has been organized in partnership with the international photography organization Fotografiska. It features 63 color and black-and-white photographs starring dead ringers for George Bush, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, Jack Nicholson, Bill Gates (using a Mac), Hillary Clinton (doodling devil horns and Hitler mustache on a Trump photo) and assorted members of the British royal family.

In town for the opening, with her favorite Trump look-alike, Jackson has been shooting her speculations of “What exactly is going on behind the White House gates” as the president makes his exit. She spoke to The Times by phone for this conversation, which is lightly edited for length.

Many of your pictures are hilarious, but many are also not funny at all. They can be quite disturbing. They feel like a kind of cultural diagnostic or, to use the photographic metaphor, an exposure of our own hungers and needs. How do you want them to land?

One of my problems with photography is that it’s a vacuum, that you just look at it. I don’t want that passivity. I want to aggravate the viewer, to make them wake up by looking at my images. Many people get very upset at them, and I find that fascinating. They see that I’m breaking privacy boundaries and ethical boundaries — which I am. I’m trying to say that we’re doing that every day of our lives.

With all the digital tools now available, you’re doing a rather old-fashioned thing, with sets and stage makeup rather than digital manipulation.

It’s authentic. What you see in front of you is the truth: It’s John Smith. You might think it’s Donald Trump, but it’s John Smith. It’s important to me that it’s not digital, that there’s a basis in three-dimensional substance. The mimicry is so exacting and so detailed, it suspends you in some form of disbelief.

What do you say to the claim that your pictures add fuel to the fire of our obsession with fame? That they don’t critique our salacious appetites but indulge them?

With the picture of Donald Trump with the KKK, for instance, I’m showing you a documentary-style picture. You can look at it and then you can decide. Donald Trump doesn’t denounce the KKK, so the implication is that he might be out there with them. I’m putting a mirror up to what’s in people’s imaginations. I’m reflecting back what is in there.

Warhol too straddled the line between exploiting the sensational and examining its nature. What influence did his work have on you?

I looked at his Marilyn picture, which was based on a standard PR still, and wondered if he was being ironic at all. He was very religious and was surrounded by icons of madonnas and saints, so he created this picture of Marilyn like one of those icons, but it was all based on a consumer-needed image. I’d look at his films, where he’s studying people getting drunk, behaving badly. He’s watching the baseness of human nature, investigating it, trying to find the truth of it. All of that I find very interesting.

As if this holiday season wasn’t surreal enough: Alex Prager’s hyper-real sculptural installation at LACMA memorializes the office holiday party.

Your titles are descriptive, straightforward, but you do add a disclaimer stating, “This is not Donald Trump” or whoever. That’s done for legal protection, but it also calls to mind Magritte’s 1929 painting of a pipe, captioned by the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” — this is not a pipe. The disclaimer attached to your work also turns it into a conceptual tease, forcing us to confront the gap between subject and representation.

It’s kind of funny, isn’t it? I wanted to make it clear. I’m not trying to kid people. I’m trying to tell them that they’re not looking at what they think they’re looking at.

Photography is a slimy, deceitful medium. It’s also seductive and powerful. When you get a fast-read photograph, a really good image that you can’t turn away from, that has you crying or laughing before you even know what you’ve seen, photography is at its strongest. At its very nature, photography is very manipulative. It incites your desire. It makes you believe — and we need a belief system. Celebrities are like mini saints. More people follow celebrity than follow religion.

Photography has long been invested with a heftier share of veracity than it could sustain. We are more skeptical about what we see in the media now, but there is still a tremendous desire to believe what we see.

The power of the image is overwhelming. It overrides anything else. You know that you shouldn’t believe it and you end up believing it. And there’s nothing you can do about it. The machine is too big, and we’re heavily influenced by what everybody else thinks. So we tend to go along with it. It can be scary. People are still wanting to believe the image more than anything. It doesn’t matter to us that it’s not real.

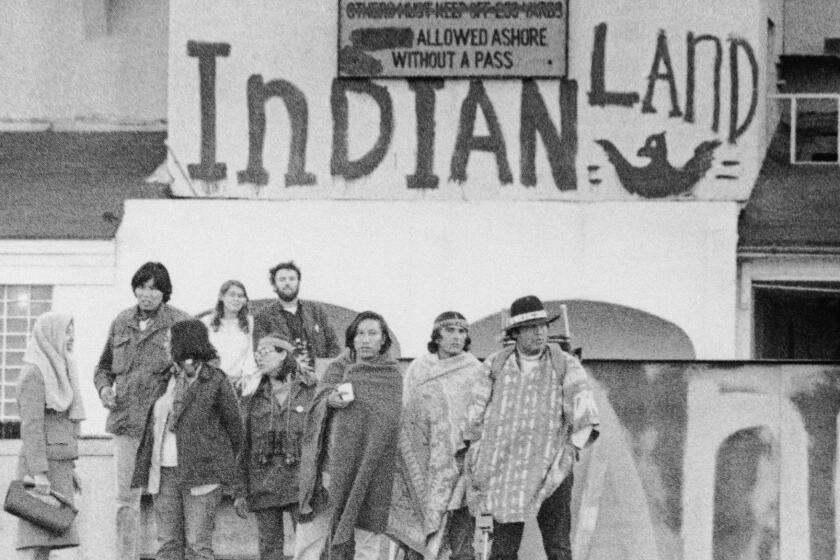

A logbook digitized by the Autry Museum reveals tribal activists and celebrities who came to Alcatraz during a 19-month occupation that began in 1969.

Your show is titled “Truth Is Dead.” If we can agree that truth isn’t entirely dead but merely on life support, does your work bolster truth’s chances of surviving or does it help yank the plug?

I’m trying to raise questions about what we believe in. When you look at my images, you think they’re true and then you realize they aren’t true. I’m trying to make it obvious that what you think is real is not real. I’m not doing it with any tricks but with actual human beings who are real.

Our lives are dominated by images. We know that we’re looking at stuff that isn’t 100% true, but how do we stop ourselves from wanting to believe in an untruth? That’s the next step, isn’t it?

‘Truth Is Dead’

Where: NeueHouse Hollywood, 6121 Sunset Blvd., L.A.

When: Extended to Jan. 20

Tickets: $14

Info: rsvp.neuehouse.com/truthisdead

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.