Early music recordings: How I got the story

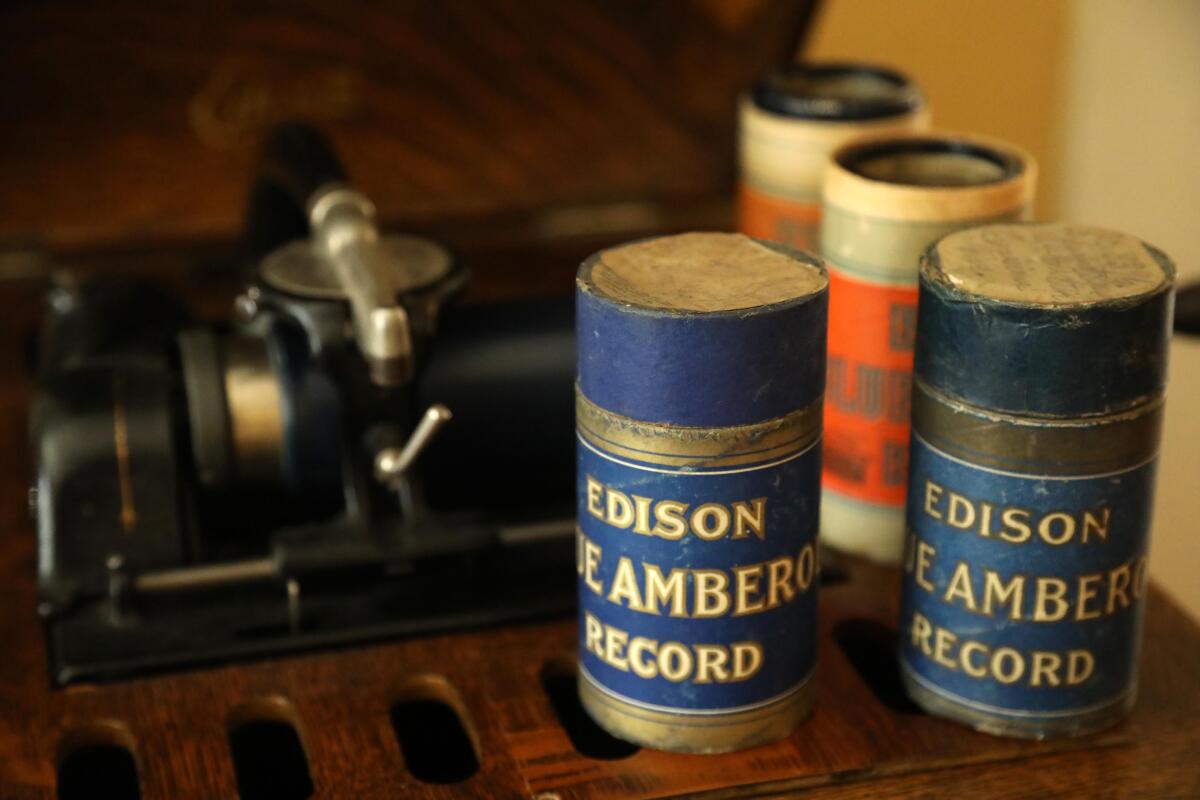

This story started in early 2019 with a toothache and the rumor of a Pasadena dentist obsessed with wax cylinders, the earliest commercial recording format.

I’d been aware of Dr. Michael Khanchalian for a while, a man who, in addition to working on root canals, spends his off-hours using his expertise with bonding agents and wax molding to repair broken or cracked wax cylinders.

A tiny tribe of passionate collectors has dedicated itself to preserving early musical recordings on wax cylinders.

I was between dentists, so I decided to make an appointment. By the time he’d checked my chompers, I knew he’d be the focus of a story, although I was still vague about the specifics. Khanchalian was long on details — he told me I needed a crown.

The next time I saw him, he was using stainless steel tools, wax and his remarkably dexterous fingers to fix me.

The dental work coincided with a conversation I’d had with Richard Martin and Meagan Hennessey, a married couple from Champaign, Ill., whose label, Archeophone Records, has earned 18 Grammy nominations for its efforts in resurrecting some of the earliest recorded American music. Martin told me that during Grammy weekend, they usually stayed at the Los Angeles home of a wildly knowledgeable collector of wax cylinder recordings named John Levin.

John Levin’s world of wax cylinder recordings

Curiosity ignited, I started getting to know both Levin and Khanchalian, who, it turns out, are dear friends. They offered a portal into the wild world of Southern California phonograph hobbyists. In turn, they hooked me up with Mark Ulano, their longtime compadre — who happens to be Quentin Tarantino’s sound mixer.

I met other obsessives at the Antique Phonograph Society’s annual convention and bazaar in Buena Park, as well as at a pre-party at the Khanchalians’ home. That led me to David Seubert, the relentlessly curious curator of the UC Santa Barbara Cylinder Audio Archive.

All these connections and relationships offered some structure and fascinating characters to the story, but I couldn’t really start writing until Levin mentioned a couple of curious cylinders he’d recently come across. They were made by the Los Angeles Phonograph Co., according to the announcer on the cylinders. The problem? No company with that name was known to exist.

Those cylinders presented a mystery — and a key to understanding the motivations of Levin and other collectors. In December 2019, I started searching newspaper archives for the earliest mentions of Los Angeles phonographs. I scoured street guides in the L.A. Public Library’s holdings, which led me to an 1893 listing of Los Angeles businesses. There, a single mention of the “Los Angeles Phonograph Co.” on Spring Street offered a revelation: My own obsessive research might have expanded the timeline of the largely unwritten history of early music in Southern California.

In all, I spent 15 months gathering information, devouring books on the early recording industry, interviewing historians and getting to know the subjects of the story. It was worth every minute.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.