Brandon Laushaul marched to the Martin Luther King Jr. monument in Compton in dress shoes, slacks and, despite the heat, a dress shirt and egg-colored sweater. It was Sunday, after all. More than that, formal attire seemed especially appropriate to Laushaul. As he marched with thousands of others in his proud city, an energy of unity seemed to have taken hold, part of a cultural reset in L.A. and beyond after so many days of uncertainty and fear.

“I’m a Compton native, and when I heard they were having a march in my city, I had to come out,” said the 23-year-old Cerritos College student. “We can all only hold in so much.”

Something, finally, might be changing, Lashaul continued, and for him, it all goes back to the history of struggle led by Black Americans in the past.

“Going back to the great Martin Luther King, he gave us an avenue to be heard, utilizing our constitutional rights,” Laushaul said. “And I feel that’s the whole reason to be here, at his monument, to exemplify that.”

The feeling is everywhere: A cultural shift over racial justice and inequality is happening, one that began less than three weeks ago but that’s been gestating a lot longer. Even for ever-shifting Los Angeles, the last few weekends have offered the kind of pole-shifting change that would otherwise be spread out over years, not days.

After we all watched the death of George Floyd with a police officer’s knee on his neck for nearly nine minutes, protests popped up in city after city.

In less than a week, Southern Californians went from gingerly stepping out in masks as businesses began reopening after more than three months in pandemic lockdown to joining massive street protests demanding justice for Floyd but also for Breonna Taylor in Kentucky, Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, and too many other unarmed Black men and women killed by police. In a way, demonstrators said in interviews over the past week, it was as though there was finally something to leave the house for, something that really mattered.

By that first Friday, several small businesses in downtown were vandalized, in many cases by people who stuck to the edges of the peaceful protests. And on Saturday, curfews were called throughout the city and county — another unprecedented occurrence in L.A. in recent decades — as a day of peaceful demonstrations throughout the city turned into a night of property destruction along Melrose Avenue. On Sunday, May 31, National Guard troops rolled in.

It was lockdown reloaded.

But the sense of chaos and disorder subsided, and a trickle of optimism began poking up from the firmament, like an L.A. spring. As riot police stood down, and some concessions were made to protest demands, the peaceful demonstrations didn’t stop. They continued and even grew.

Walter Mosley, Luis Rodriguez, the coiner of #BlackLivesMatter and others sketch a hopeful future for L.A. and the U.S. after George Floyd protests.

The movement seemed to shift. Now, the call was not only for an end of police brutality but maybe the entire idea of policing as we know it. And more people joined. By this past Sunday, after tens of thousands streamed through the streets of Hollywood, Compton, Santa Ana and dozens of other demonstrations across Southern California under perfect late-spring sunny weather, it was clear that this movement wasn’t going anywhere.

These are a few key societal trends emerging from the ongoing nationwide protests calling for an end to police brutality and for racial justice.

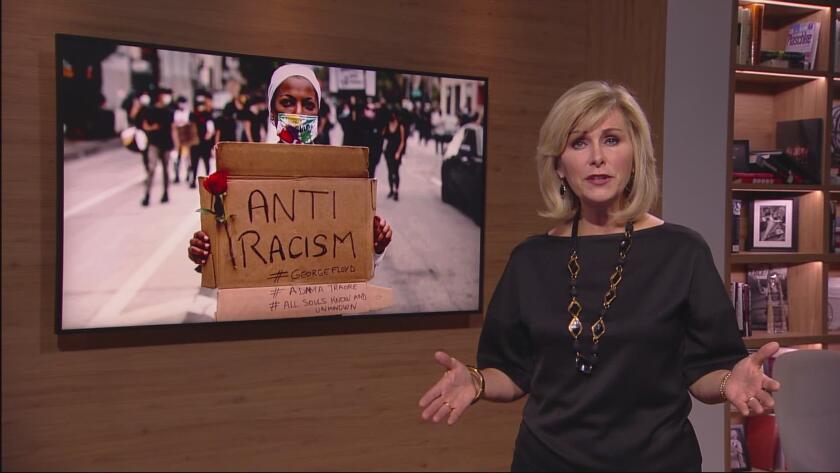

The antiracist shift

The most key shift is a new cultural consensus: It is no longer enough to be nonracist. People should strive to be antiracist. That is, someone who actively works to end racism in society and does not passively ignore racist actions or comments in their surroundings.

The growing numbers of non-Black faces at demonstrations in L.A. and across the nation show a turning point in understanding the need to frontally combat racism. For too long, Black activists were joined by too few non-Black allies.

“To see it again is just exhausting,” said Irene Tello, a Compton native who marched last Sunday alongside Black neighbors and counterparts.

Yet the scope of the protests broke into previously unseen connections. When a conservative political figure like Mitt Romney is also saying the words, “Black lives matter,” you know something has changed.

The author of ‘How to Be An Antiracist’ has a timely new spinoff board book, ‘Antiracist Baby,’ out soon.

Ibram X. Kendi, author of “How to Be an Antiracist” and founder of the Antiracist Research and Policy Center, has said that true change will take time. Yet he’s put a target date on the matter.

“I don’t know whether every single person can be antiracist by 2030, but I do have hope that every racist policy could be eliminated by then. That would be great,” Kendi told Erin Aubry Kaplan in an interview in The Times.

“White people are seeing racial injustice, they’re seeing Breonna [Taylor] and George [Floyd], and they’re seeing the cause of death was not Breonna or George; it’s racist policing,” Kendi went on. “Now they are seeking to transform the policy, and that’s a good thing.”

The process is happening on many fronts. One of the most dramatic: the toppling of Confederate statues. Some of the actions are being done by protesters, but many monument removals are being sanctioned by government officials across the South.

And though it was released in March, it’s worth noting there’s a video game, “Treachery in Beatdown City,” generating interest for the way it promotes antiracism. The Times’ Todd Martens described it as one of the “most relevant, of-the-moment video games of 2020.”

Mostly overlooked in the “Animal Crossing” craze, “Treachery in Beatdown City” is a game in which you fight racists. Behind its humor and retro look is bracing political commentary.

Defund the police

The Black-led protests early on in Minneapolis and in the major cities that followed have not just been about spectacle or release, the sort of typical media narratives around civil unrest. They are organized to buoy specific policy demands, and so far, the tactic has been working.

An immediate goal set by the demonstrations is to defund police departments. In Los Angeles, the mayor and City Council announced they would formally seek ways to decrease LAPD funding by up to $150 million.

And just like that, in a matter of days, what may have once been considered an improbable outcome of the demonstrations is now being treated as legitimately on the table.

Up and down the pop scale, from late-night comedy news shows to local broadcasts in Los Angeles, the term “defund” or “defunding” entered the lexicon. Both terms hit what is referred to as peak popularity (or a value of 100 in maximum of Internet search interest) according to Google Trends on June 5 and 6. Media figures of every stripe are already chiming in.

“‘Defund’ means that Black & Brown communities are asking for the same budget priorities that White communities have already created for themselves,” wrote Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) on Twitter on Tuesday. “People asked in other ways, but were always told, ‘No, how do you pay for it?’ So they found the line item.”

Abolition

The theater of the possible has gone even further. Core among the ideas dancing closer to the mainstream is imagining a world without police — at all. “Absolutely this is about abolition,” Melina Abdullah, one of the leaders of the police-reform movement in Los Angeles and organizer with Black Lives Matter-L.A., told cheering demonstrators at the George Floyd memorial in downtown L.A. on Monday.

“It’s really important when we say abolition, we mean tearing down the system of policing that we are now submitting to, and also building something new,” Abdullah said.

Priscilla Ocen, a professor at Loyola Law School and member of the Sheriff’s Department Civilian Oversight Commission, watched from a safe distance as a legal observer that day, in a double mask. Ocen said later that “outside of activist circles and outside of intellectual spaces in Black and brown communities” police abolition and prison abolition were usually treated as fringe ideas.

“I think in the space of the last couple of weeks it has taken on a different tenor, it’s become a mainstream alternative to how policing functions, and the state violence that’s attached to it,” Ocen said. “It’s been a huge shift in a short period of time but it’s actually decades in the making, especially abolition.”

So far, Minneapolis City Council leaders have declared they will seek to disband its police department and rethink public safety in a way that relies on mental health and social workers for many of the domestic calls police routinely handle. Here in L.A., there’s not a lot of such talk at the elected level — yet. But there are rumblings. United Teachers Los Angeles, fresh off its 2019 strike, has already pledged to support an effort to eliminate the Los Angeles School Police Department.

Reckonings in the press and publishing

Change also has come to an American institution that is among the most reluctant to be in the news — the news business itself. Since the George Floyd protests began, Black journalists and journalists of color broadly have begun confronting systemic biases and racism within the semi-sanctified halls of America’s legacy news organizations.

It started with the uproar over a column by Sen. Tom Cotton in the op-ed section of the New York Times. Staff members on the news side organized and decided to publicly defy the strict rules related to social media held by the N.Y. Times, tweeting en masse: “Running this puts black @NYTimes staff in danger.”

Editorial page editor James Bennet resigned last Sunday.

Ever since, an outpouring of testimonies from journalists of color related to discrimination, mistreatment or racism in their workplaces have not stopped, including at this very newspaper, where on Tuesday, Executive Editor Norman Pearlstine sent a memo to staff members pledging even more changes aimed at hiring and promoting more journalists from underrepresented communities.

The editor also said that effective immediately, The Times would change its style to capitalize the term “Black” when referring to people of the African diaspora.

The reckoning is real. After facing a public airing of lingering internal grievances over racism and discrimination, the editors of Bon Appetit, Variety and the Philadelphia Inquirer also have resigned or gone on leave.

At the historic Philadelphia daily, the resignation of Stan Wischnowski came after the newspaper published a headline reading “Buildings Matter, Too.” And over at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, a different sort of maelstrom brewed over a Black female reporter’s postings on social media, with other staffers coming to the defense of 27-year-old Alexis Johnson, who was barred from covering the protests in her city after highlighting an irony in how images of disorder are treated when they involve white fans at a country music concert.

Speaking on PBS NewsHour on Tuesday, Pearlstine seemed to suggest that the after-effects of the George Floyd protests may transform the news industry in a more fundamental way: “We don’t think twice in saying that antifascism would be part of our mandate as a journalistic institution. Antiracism should be similarly central to our core.”

Meanwhile, after writer L.L. McKinney started the social media hashtag #PublishingPaidMe, the disparity between white authors and authors of color has been laid bare, sparking serious conversations about racism in publishing.

Corporate commitment

The shifts have reached all the way to America’s major boardrooms. In recent days, companies large and small have publicly stated a commitment to social justice and to ending racism, moves that in some sectors have been met with a healthy degree of skepticism.

U.S. companies have donated more than $450 million to civil rights groups since the George Floyd protests began, according to a review by the Financial Times. On social media, major brands have stated their positions, among them Netflix, which tweeted on May 30: “To be silent is to be complicit,” in a theme that has multiplied among brands in the days since.

Facebook, Amazon, Google, Spotify, Verizon, Goldman Sachs and Target are among companies that pledged gifts to social justice causes of $10 million or more, reports said. Warner Music Group announced a $100 million fund with a foundation last Wednesday. Two days later, Sony made the same fund announcement, a pledge of $100 million.

But activists have pointed out inconsistencies in messaging versus actions in the flurry of corporate posturing over Black lives. After NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell stated the league was wrong to not listen to its players about racism, he was challenged to prove it by ensuring a team would hire quarterback Colin Kaepernick.

And when Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg on Sunday announced a donation of $10 million to social justice causes, critics cast doubt on his intentions, pointing to his refusal to bar President Trump from posting comments to Facebook that many see as promoting violence, The Times’ Johana Bhuiyan reported. Employees at the social media giant organized a work stoppage to protest Zuckerberg’s justification of keeping Trump’s posts.

Similarly, CBS was called out for letting police use its property during demonstrations in L.A., and Amazon was admonished for partnering with police in surveillance products. Will the “bandwagon” subside? For skeptics of the outpouring of corporate commitment to racial justice, companies might be responding with jitters to findings of a new poll that showed up to 60% of U.S. consumers would boycott or buy from a brand based on its response to the protests.

“It’s good that they’re writing checks,” said Abdullah, in an interview Thursday, referring to the surge of corporate interest in the new movement. “We have to make sure that those checks are directed to the right organizations. We need to make sure that the war on Black people doesn’t get buried under a larger quote-unquote ‘diversity’ effort, where Black people often become erased and invisibilized.”Antiracist apparel

Wayne Nelson has a T-shirt store in Pasadena and has been coming out to the anti-police-violence demonstrations near downtown L.A. selling lots of black T-shirts with white sans serif lettering spelling out political statements relevant to the moment, involving themes related to Black Lives Matter.

He held up masks he just had made, black and printed with white letters: “I can’t breathe.” Other bestsellers are his Nipsey Hussle tees. “There’s a whole lot of ways this system chokes African Americans,” Nelson said, under a hot afternoon sun, referring to his masks. “That’s what this is about, I can’t breathe.”

He’s part of a cottage industry of apparel and gear that has accompanied the major street happenings of our era in L.A. The last major outpouring of new momentous tees came with the death of basketball great Kobe Bryant. Nelson said he was there too.

“My talent is buying and selling, I listen to what people want, I go ahead and get it and bring it back to them,” Nelson said. As soon as officials announced the recommendation to wear a mask at all times in public spaces, Nelson said: “I knew what I was selling, wasn’t no doubt in my mind.”

The Black Lives Matter demonstrations have added a new layer of meaning for him, he added, as he welcomed his daughter and niece, who just then arrived to the grassy lawn of Grand Park, west of City Hall, proudly wearing their own Black Lives Matter T-shirts. They were ready to sell.

A culture of giving

Madison Calderon had gauze, bandages and a box full of 60 peanut butter-and-jelly sandwiches she had made herself, all in a wagon she brought down to L.A. City Hall, so she could offer help to the throngs of people out to honor George Floyd however she could.

The 22-year-old from Pasadena wore a face covering as she described her activities last Friday. “I’ve been going to the 99 Cent store and just getting as much as we can, I’ve been getting like six loads a day,” Calderon said. “I’ve given out two Band-Aids, which is nice, I’m glad I haven’t had to use them.”

There has been more mutual aid happening at the George Floyd demonstrations in L.A. than during any of the recent string of popular protest movements that have swept through this city in the last decade — arguably more prevalent than during the antiwar movement, the immigrant-rights marches and the women’s marches, demonstrators said.

Mostly it has been disposable water bottles. They’re piled up on sidewalks in packets of 24, the kind that are cheap and ubiquitous at supermarkets and pharmacy chains, left there by volunteers. Everywhere a marcher turns, there’s someone within reach willing to give them hand sanitizer, a snack, a piece of fruit or a plastic bottle of water.

In Compton, Michelle Merritt, longtime leader of Compton Girl Scout Troop 943, stopped her van amid the march route and began handing out bottles of water from ice chests with help from her daughters. “Because I’m 61, I can’t do a lot of walking,” Merritt said. “But I can pass out water, and that’s what I’m doing.”

This spirit is most prevalent and concentrated around City Hall, where medic stations have been set up during the big demonstrations in case of any injuries. For Calderon, who attended the Women’s March and said it “wasn’t the same vibe,” these anti-police brutality protests offer a chance for anyone to get involved. Much of the organizing is happening through social media.

“I want to be out here in the most constructive and positive way. My friends have been posting about resources, and you can put on a Band-Aid, you can cook rice, you can come out and be helpful,” Calderon said. “On top of that, quarantine I feel has made everyone come out, it’s just worse, on worse, on worse, and I hope that makes people want to change it.”

Reporter Daniel Hernandez describes the rapid culture shifts since the killing of George Floyd to LA Times Today host Lisa McRee.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.