Commentary: George Walker is the black composer you should know but don’t. Why that may change

Richard Valitutto offered an impressive Piano Spheres program at the Colburn School’s Zipper Hall this week. He covered the transgressive keyboard waterfront, exploring the idiosyncratic ways of banging and sounding and resounding that occupy composers of today, young and old. Crafty sonic sensuality and even, with a surprisingly and deliciously sentimental six-minute Poulenc closer, sonic bisexuality gloriously prevailed.

The recital Tuesday, however, began surprisingly with George Walker’s Piano Sonata No. 5. It also was around six minutes, but it was in a declamatory style that might have seemed to have nothing to do with anything else on the program.

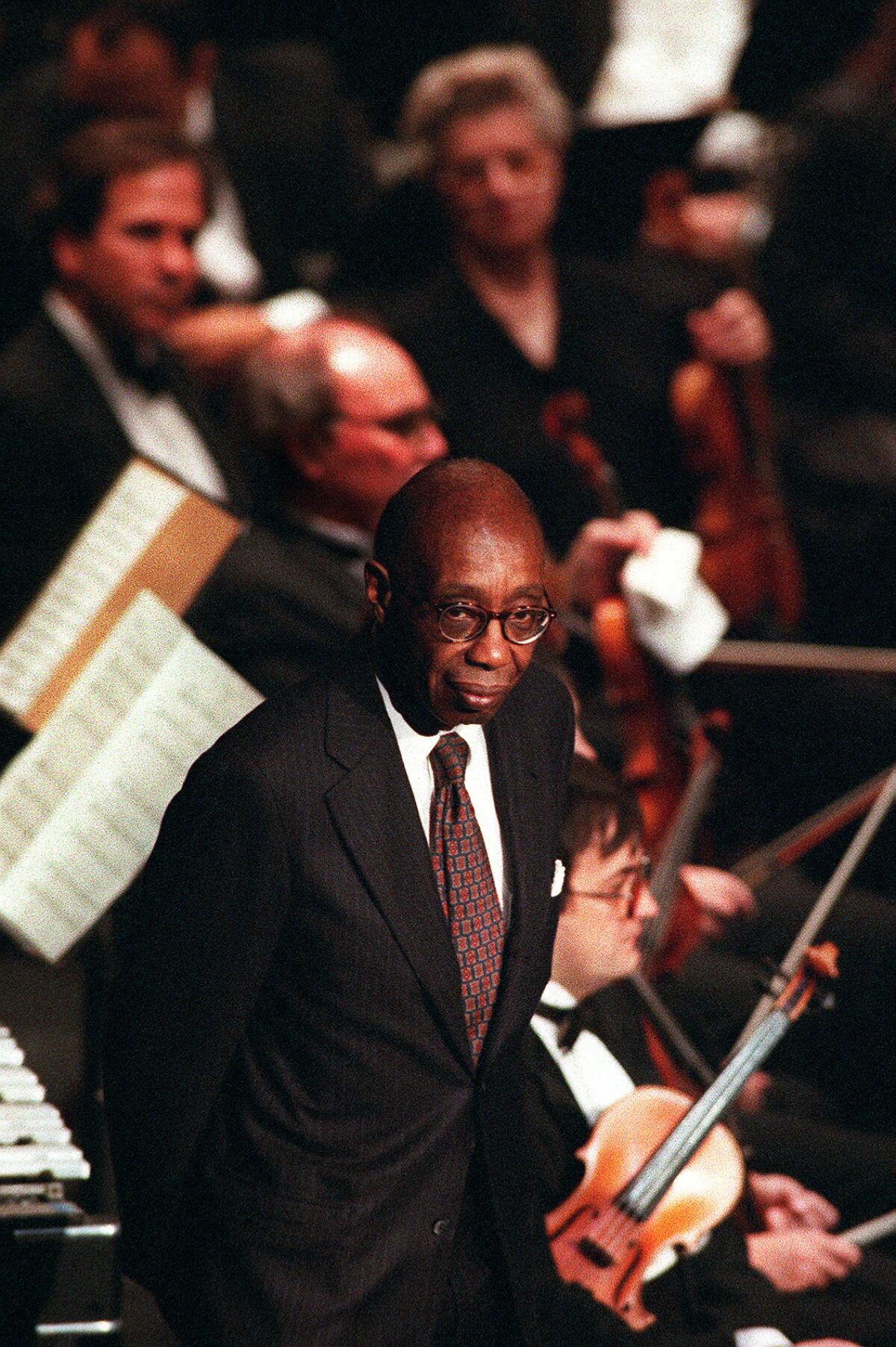

Walker, who died in 2018 at age 96, was one of America’s most distinguished composers. He won the Pulitzer Prize for music in 1996. He was a superb pianist and an esteemed academic. His shelves and walls were overloaded with the awards and honorary degrees that go with a legendary career. He wrote around 100 pieces, and many of them have been recorded.

No history of American music is complete without Walker, and that means many a standard history of American music is incomplete. Who among classical music lovers, let alone the general public, even knows who George Walker was, much less has heard his music?

Among all else, Walker, the grandson of a slave, was the first African American classical musician to break a color barrier. Had he been a member of the Harlem Renaissance, I have no doubt he’d be widely read. Were he an Abstract Expressionist painter, you’d be in gravy if you had been savvy enough to have bought work before museums put on exhibitions.

Maybe that’s not quite fair. Walker has never been entirely off the radar, and last year the Seattle Symphony garnered a certain amount of attention when it gave the first live performance of Walker’s last completed score, “Visions.” The fifth in a series of symphonic works he called sinfonias and completed in 2016, it pays tribute, with compelling forcefulness and affecting grace, to the victims of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church shooting a year before in Charleston, S.C. At the time of his death, Walker was working on a piece for the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Walker’s music is uncompromising. It can be thorny. Like Bach, Stravinsky and Webern, he made music with a jeweler’s precision, and he didn’t wear his emotions on his sleeve. Like their music, his work demands — and magnificently rewards — deep listening.

Even so, about the only month in which I ever encounter a piece by Walker on a concert program is February, because that is Black History Month. Walker gets all the respect in the world for being an important black composer. He just doesn’t get nearly enough love for his music and has far too long lacked enough champions among our most prominent performers.

But once you get the Walker bug, you begin to think that this has to change. This just might be the moment it will. Valitutto opening a hip recital with the Fifth Sonata feels like a sign. It is a piece that grabs immediately. For a second or two, it sounds as though it came from modernist 1930s, in the manner of a young Copland. No, it’s too crystalline for that. More Stravinsky instead. No, not that either.

Before long it dawns on you that the sonata inhabits a world of its own. Its strength is in Walker’s confidence in the potential power contained in a grouping of a few notes. Hearing them in a Walker-ian way is akin to studying a leaf under a microscope to understand a tree. The word that comes to mind when I listen to Walker’s works is “nourishment.” They offer some kind of mysterious sustenance.

The Piano Spheres recital wasn’t the only hint of a Walker moment, however tenuous. The sixth piece on a new recording by the venturesome violinist David Bowlin, on the trendy Brooklyn New Focus Recordings label, is a must-hear new work: “Under a Tree, an Udatta” by fashionable recent Pulitzer Prize winner Du Yun, on whom the L.A. Phil and Los Angeles Opera are keen. The fourth piece on the recording is Walker’s enigmatic, virtuosic 2011 violin solo “Bleu,” an unexpected look at the blues as only Walker might.

Last week the BBC’s classical music station, Radio 3, a mainstay of Britain’s musical life, just happened to make Walker composer of the week, devoting an hour a day, Monday through Friday, to an illuminating discussion of Walker’s music with his son, violinist Gregory Walker.

The series is archived for a month on the station’s website, and it is an ear opener. Walker had strong reasons to cover his emotions. He was a graciously expressive pianist (there is wonderful performance from 1956 of him playing Brahms’ Second Piano Concerto), but a concert career meant dealing with racism on two levels. One was exclusionary. The other, especially in Europe, was condescending.

Ultimately, Walker found he had the best chance for a career in academia, most of it spent at Rutgers University in New Jersey. He was said to have been a demanding teacher as well as a highly self-critical composer. His African American identity is clearly in his music but sometimes found only deep under the surface. An Ellington tune or a spiritual might take an analytical sleuth to find, the notes elongated, played backward or otherwise hidden in the compositional DNA.

Walker’s music takes much of its vitality from an inner rather than outer sense of identity. He had to endure always being identified as the first black to graduate from the Curtis Institute of Music, where he studied with Rudolf Serkin, or as the first black composer to win a Pulitzer. He lived haunted by what his grandmother said it was like to have been slave: “They did everything but eat us.”

All of that is in his music, with its celebration of identity, its heartbreak, its elegance, its thrill of being, its honesty. But Walker buries his ego. He doesn’t give away easy emotion. There are no easy outs in Walker’s music; what he has to say is too important for that. He insists that listeners enter into expression rather than be told how to feel. Good places to start with Walker are his piano and violin concertos. When you get under their skin, they will get under yours.

They, along with a whole host of solo, chamber, orchestral and vocal works, are just waiting for major soloists and conductors to discover them. Thanks to Albany Records, which has made a cause of Walker’s music, and other labels, discovery is not all that difficult. Yet, as with the BBC composer of the week, we have to turn to Europe, the only place where many of the orchestral pieces could be recorded.

It doesn’t have to be that way.

Beethoven mashed up with Philip Glass? Christian Schmitt’s ode by organ? A loud walkout at Monday Evening Concerts? The Year of Beethoven has begun.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.