L.A. artist Nayland Blake toys with race and queerness, plus a bunny suit

Playful works imbued with darkness, kink and sugary baking scents are part of Nayland Blake’s 30-year retrospective “No Wrong Holes” at ICA LA.

You smell it before you see it.

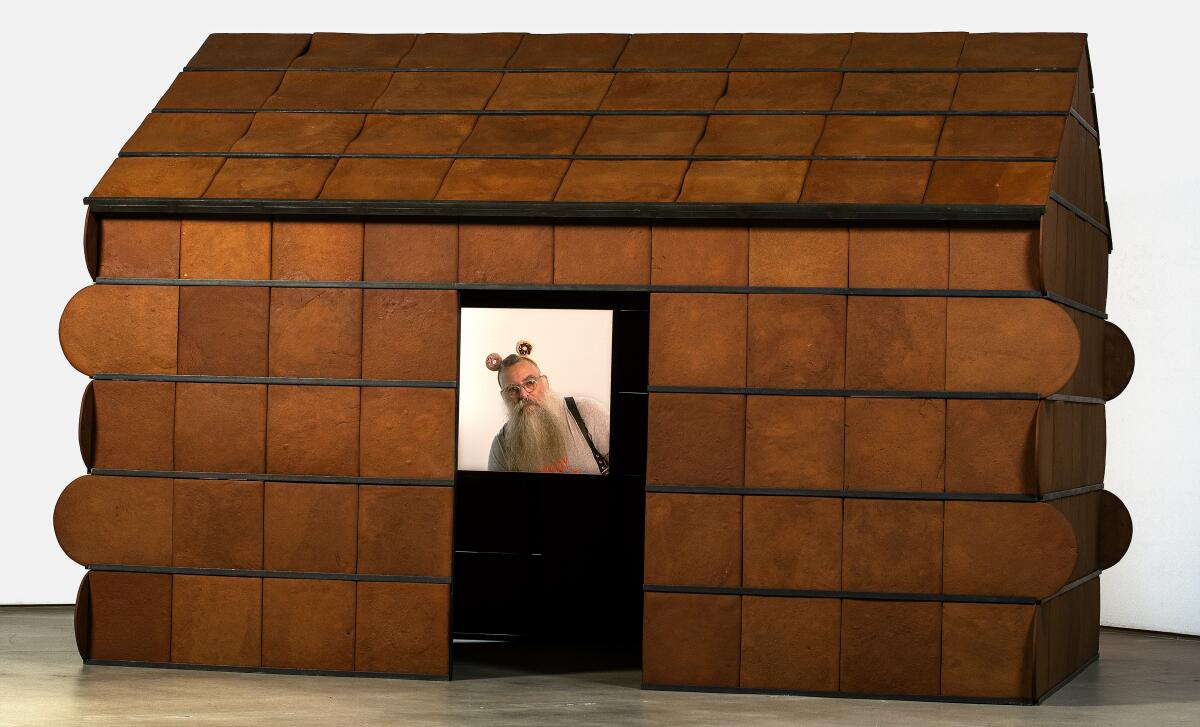

A waft of butter. The sharp snap of ginger. Soon you realize you’re inhaling the earthy sweetness of gingerbread. But you are not in a bakery. You are in the middle of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles — standing before a massive gingerbread house by artist Nayland Blake.

The piece, from 1988, is titled “Feeder 2” and was inspired by “Hansel and Gretel,” the Brothers Grimm fairytale about a pair of siblings who are lured into a tasty gingerbread cottage only to find that it’s a trap set by a cannibalistic witch. Like the story, this adult-sized gingerbread house, which checks in at a height of 7 feet, seduces with its scent and its proportions. But linger too long in its vicinity and the sweetness can begin to overwhelm.

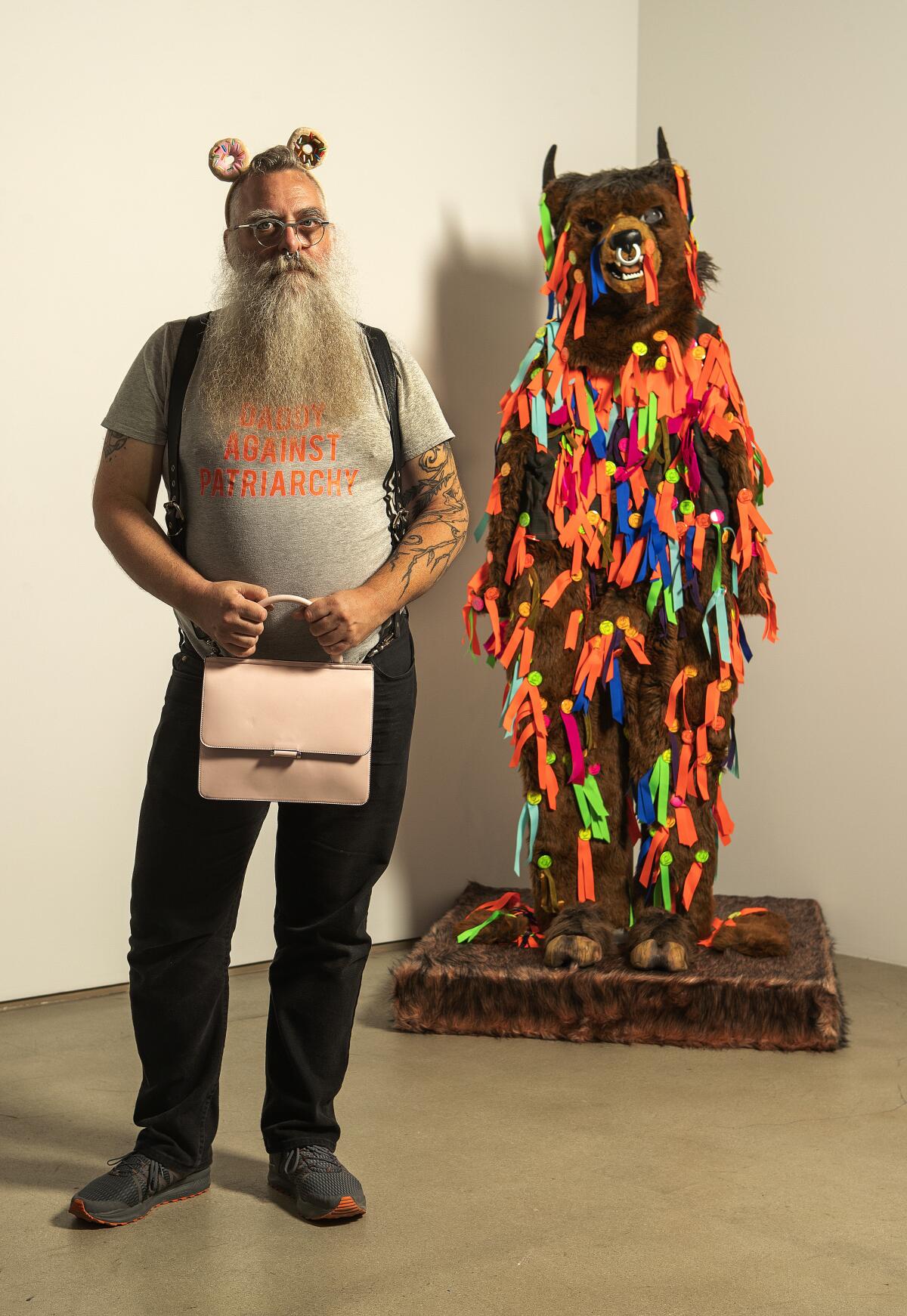

“It’s about what happens when you get exactly what you want,” says Blake, who on this warm Thursday afternoon is accessorized with a doughnut headband and a T-shirt that reads “Daddy Against Patriarchy.” The New York-based artist (who uses nonbinary gender pronouns) navigates around half-opened crates at the ICA LA as they prep for their most comprehensive career retrospective to date, “No Wrong Holes: Thirty Years of Nayland Blake.”

“You can’t spend a lot of time inside of it really,” says Blake of the gingerbread installation. “It’s really intense, the butteriness.”

They originally made the sculpture on a lark, a one-off to be shown at Matthew Marks Gallery in New York in the late 1990s, the commercial gallery that has represented them since 1992.

“It was never going to sell,” Blake thought. Yet it ended up becoming a signature piece. (In fact, it was shown at the Hammer Museum in 2014.)

Blake does not regularly make architectural installations out of baked goods, but with its overtones of temptation, surrender and foreboding, it touches on themes regularly explored in the artist’s work.

Over a career that dates to the 1980s, including formative years in San Francisco and Los Angeles, the influential artist, curator and teacher (Blake chairs a joint master’s program run by Bard College and the International Center of Photography in New York) has become known for visceral works. These include performance, but also sculpture and assemblage that take everyday objects — shoes, toys, record albums, bondage gear — and uses them to pick apart social categories such as gender, race, queer sexuality and the fraught points at which they can meet.

A sculpture in the retrospective titled “Ibedji (Quick),” from 1996-97, for example, synthesizes a number of the artist’s concerns in a single glass case. The assemblage references the ibeji of Yoruban culture (carved effigies of twins) — in this case expressed as a pair of matching Nesquik bunny bottles. Buttons reading “Master” and “Boss” are also included, objects acquired through the artist’s involvement in fetish and BDSM (bondage and discipline, dominance and submission and sadomasochism) scenes, and words that echo the argot of slavery.

“Ibedji (Quick)” conjures the complexities of Blake’s hybrid status: queer and mixed-race, the fair-skinned child of a white mother and black father who is frequently confused for white. Of the piece, Blake says, “I was thinking about being the inheritor of two traditions.”

Like the artist’s larger body of work, the piece tackles difficult ideas with mordant humor and the detritus of everyday life. The modestly scaled piece is a portable altar of sorts, with cork, cigars and beads — a ritual ceremony-to-go. At its heart are the Nesquik bunny bottles: one chocolate brown, the other strawberry red.

Jamillah James, curator of the exhibition, says that Blake, throughout their career, has taken difficult topics such as “racial relations and the history of racial terror” and found ways “to undercut that with an incredible sense of humor and playfulness.”

In conceiving the retrospective, this was something James sought to highlight.

“The way we thought about it is the idea of play and the way that play can be articulated in different ways,” she says. “Play with dolls, but also intimate play, things that are suggested to the viewer, imagining oneself in one of those contraptions that Nayland has made.”

The artist has made frequent use of bondage play in their work, including latex masks, cuffs and restraints. These are objects that address sexuality, but also connect with larger issues of literal human bondage.

“What does it mean,” Blake says, “for a descendant of slaves to be interested in imagery of chains and shackles?”

When installed in pristine, white-box spaces, the works also read as biting critiques of Modern and Minimalist cool — Dan Flavin or Donald Judd through the lens of spanking.

There are cuddlier elements, too: dolls and plush toys, particularly rabbits, an animal that embodies elements of cunning, heightened sexuality, and gender play. Bugs Bunny, after all, was famous for cross dressing.

Perhaps most poignant is the video piece “Starting Over,” from 2000, which shows the artist in a massive bunny costume that has been stuffed with 140 pounds of dried beans — the weight of Blake’s partner, Phillip Horvitz at the time. (Horvitz, a performance artist, died in 2005.)

In this cumbersome ensemble, Blake proceeds to execute a series of dance moves at Horvitz’s command. It is as a reflection on coupledom, dominance and struggle — all in a dancing bunny.

“I like the idea of it being kind of pathetic,” they say. “I like the idea of it being disarming.”

Blake was born in New York in 1960, partly through the vagaries of fate. Their parents were from New Bedford, Mass., but moved to New York City.

“When a twenty-something black man got an 18-year-old white high school student pregnant, their families kicked them out,” says Blake, noting that this was an era in which interracial marriage was still illegal in numerous states. “They basically ran away to New York.”

New York ultimately supplied some of the artist’s most formative experiences: gazing at the dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History, going to the 1964 World’s Fair and standing over the Panorama of the City of New York, a sprawling 3D model of the city that renders all five boroughs at 1:1200 scale. (It’s now on long-term view at the Queens Museum.)

The artist loved the idea of these invented worlds.

“The idea that I could project myself into those spaces,” they say, “that same kind of space as a Joseph Cornell diorama, that I could escape into there.”

Blake came of age in Manhattan in the 1970s. This was a time when swaths of the city were going up in flames and President Ford was refusing a federal bailout of the nearly bankrupt city, generating headlines such as the infamous “Ford to City: Drop Dead.”

“The thing that was amazing about New York in the ‘70s is that no one wanted it,” they say. “So there was this possibility of making stuff out of it.”

In high school, Blake fell in with a group of “art nerds,” attending Fluxus events and happenings staged by the likes of Charlotte Moorman, the avant-garde cellist who was once arrested for playing topless.

“The art world I grew up seeing was not one where anyone was making money or even necessarily having careers,” says Blake. “That was super important.”

A devotee of film (they were a regular at the Anthology Film Archives, which specializes in experimental work), Blake decided to study cinema when they were accepted to Bard College. But they ultimately shifted to sculpture under the influence of artists such as Jonathan Borofsky (of the famous “Ballerina Clown” sculpture in Venice and “Molecule Man” in downtown L.A.) and exhibitions such as “Times Square Show,” the immersive contemporary art show staged by the group Colab in 1980.

“That diorama I’m fascinated being inside? I could do that,” Blake says. “The only name I could give to that was sculpture.”

After Bard, they moved to Los Angeles to complete their master’s in fine arts at CalArts. (They received their degree in 1984.) But the school, segments of which could be doctrinaire, wasn’t a great fit.

“A visiting artist would come and it would be blood sport to see who could be the first person to ask the first question that stumped the person,” Blake recalls. “It was a critical pile-on that was theory-based, and it was very pessimistic about the act of art making.”

The school, however, “did knock me off of presuppositions ... that’s a really valuable experience,” they add. It also put Blake in a cohort that included artists who were also toying with themes of gender and identity, such as L.A. painter Judie Bamber and performance artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña.

It was Blake’s move to San Francisco in 1984, however, that changed everything.

“It was the gay capital,” they say. “And also this place that was off the radar of the serious art world at the time.”

A place that, like the New York of the 1970s, was rife with possibility: “A whole generation of people arrived there and we didn’t have an understanding of why we couldn’t do what we were doing, so we just did it.”

Blake found their voice in San Francisco and became known not only as an artist but a curator. Along with Lawrence Rinder, Blake organized the ground-breaking show “In a Different Light,” which explored LGBTQ experience in 20th century art.

Blake’s own work was inspired by important Bay Area conceptualists such as David Ireland and William T. Wiley, whose “hippie funkiness” bore none of the austerity of East Coast minimalism and conceptualism.

“It was messy and inelegant for people to look at,” says Blake. “That seemed interesting to me.”

In that period, the artist became known for pushing art in San Francisco in new directions. They incorporated gay porn and fetish objects into assemblages and installations, which referenced queer identity, BDSM and San Francisco’s leather daddy scene.

One work from the early ‘90s assembles musical album covers that show the ways in which popular singers have toyed with gender, such as Lou Reed’s 1972 album “Transformer,” which showed a man in both macho and feminine poses and dress.

“I was thinking about that kind of gender performance,” says Blake. “This catalog of sexuality.”

These explorations invariably bumped into the issue of race.

“When I was first around gay men in New York, they would use terms like ‘coal digger,’” the artist recalls. “If you were a white guy into a black guy, you were a ‘coal digger.’ ... This casual racism around, particularly black men, was matched by misogyny.”

Blake’s fair skin has made the artist privy to the things people say when they think a black person isn’t in the room — and how to confront those moments. “For me to be like, well, you’re in the room with a black man,” they say. “The incredulity that I would get from people.”

Themes of race and racism are perhaps most potently sardonic in Blake’s drawings, which they began to produce in greater volumes after moving back to New York City in 1996.

Their imagery includes charged symbols such as chains and nooses, but also cartoonish figures evocative of Brer Rabbit (the folk tale inspired by African folklore) and Krazy Kat, the early 20th century comic created by mixed-race cartoonist George Herriman, who passed for white.

The range of subjects that Blake has addressed in their work, and the range of materials they have occupied, has made it difficult for them to occupy a tidy niche in the art world.

“The art world has very little patience or ability to deal with hybridity, to deal with these things across bandwidth,” Blake says. “It likes to file people in one location.”

But the retrospective at the ICA LA has gathered all of the artist’s concerns under a single roof.

James says they have produced work “in such an elegant way, and in a darkly comic way.”

To see their life’s work in a single space, “it’s really moving,” Blake says. “It was all this stuff that I made relatively quickly.”

With the retrospective, it’s acquired a sense of permanence.

“It’s interesting ,” Blake says, “to see it turned into history.”

"No Wrong Holes: Thirty Years of Nayland Blake"

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.