Ethan Coen is ‘giving movies a rest.’ His focus for now: ‘A Play Is a Poem’ in L.A.

Ethan Coen’s “A Play Is a Poem” is having its world premiere at Los Angeles’ Mark Taper Forum this month. The five one-acts that make up the work represent distinct genres and time periods, and they take place all over America.

So where did the inspiration for these scripts come from? Why are these five pieces being performed together? And the title “A Play Is a Poem” — well, what does Coen mean by that, exactly?

“I don’t know,” Coen said.

“I should have thought about this — you’d think I’d have an answer ready, since it’s the ... title of the play,” the seasoned filmmaker said, seated in the Taper just days before the play’s opening Saturday.

“I’m not being coy or withholding,” he added with a shrug. “It’s just that I’m so unreflective about my own process and unself-conscious about it. These are natural questions, but I don’t think about that. I just … it’s like … I don’t know.”

What Coen does know is that theater seems to satisfy a creative impulse that movies — even Oscar winners like “Fargo” and “No Country for Old Men,” cult classics like “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” and “The Big Lebowski,” or experimental anthologies like “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs” — do not.

Cameron Crowe explains how he’s updated his love letter to the Led Zeppelin and Lynyrd Skynyrd era — and tweaked the key part of a teen girl groupie.

“I feel totally comfortable with movies. My brother and I have been making movies since we were kids,” he said of Joel Coen. “But working on movies is such a piecemeal, technical thing. This is the exact opposite of that — this is a fluid, fragile thing where everything affects the next thing.

“What’s terrifying about that is it can all go to hell in an instant. You make a wrong decision in rehearsals, and it’s just not like making a movie, where you can always retrieve errors and slap stuff together and make sense of it in a different way. This, my God, it’s really different.”

So while Joel is writing, producing and directing his first feature without his brother — a big-screen adaptation of “Macbeth,” starring Frances McDormand (who is also his wife) and Denzel Washington — Ethan told The Times he is “giving movies a rest” and polishing up this play, which runs at the Taper through Oct. 13 and moves off-Broadway in May.

Coen was first exposed to theater as a child but he didn’t actually enjoy it until he moved to New York City. “As a kid, my parents took me to the Guthrie Theater, the big regional theater in Minneapolis,” he recalled. “It was kind of like a temple of art. My parents would get dressed up, I was probably mostly bored. I can’t remember what I saw there.

“It took me a while to get over that, but I’ve recovered in a big way,” he added with a laugh. “It’s funny, I had this total prejudice against the thrust [stage, which extends into the audience on three sides] because the Guthrie Theater had one. I’ve never not done proscenium, but now I’m getting into it. It’s part of what makes 700-something seats seem so connected to the actors.”

In many ways, “A Play Is a Poem” is a tribute to theater itself. Written between film scripts over the last 10 years, the scenes take place across decades and cities in America. Coen clarified that he’s not trying to make any profound comment on the country at large, and that the one-acts aren’t connected by any overarching story line or theme: “It’s just because I’m American, and I like private-eye fiction, I like country music. It’s just the stuff I like.”

Instead, the show directs focus to the immovable parts of the medium. The ability for an actor to play multiple characters in a single production, as its 10-person ensemble does for the five scenes. The rhythm of the spoken language, and how its variations can dictate the comedic or tragic sentiments of an entire story. The audience’s freedom to watch Nellie McKay sing and play the ukulele, piano and xylophone between scenes, or the stagehands, wearing canvas jumpsuits and headphones, change the set props onstage. “It’s kind of like a three-ring circus — you can look wherever you want,” Coen said.

Between vague responses, Coen stared in a kind of awe at the stage, a generously sized semicircle of hardwood floor and faux brick wall that — with just a few strategic props, costumes and special effects — transforms into the hillbilly hollows of Appalachia, a tenement apartment in New York City and a picturesque garden in Natchez, Miss.

“Look, this is not, you know, some version of reality. It’s a desk and two chairs,” he said, pointing to the props left onstage after the afternoon preview’s final scene, set in an executive suite in Hollywood. “I mean, look at it. It’s a different exercise making a story out of that than out of everything you have to work with on a movie, where there’s so much that can pass as reality. That’s not a challenge for me.”

He then pointed to the stage. “That’s interesting,” he said with a smile. “Yeah, I’m interested in that. People think it’s about, like, self-expression or something, and it’s not about that. You do it because it’s involving and stimulating and you like the process of doing it. And damn, there’s something fantastic about it when it works.”

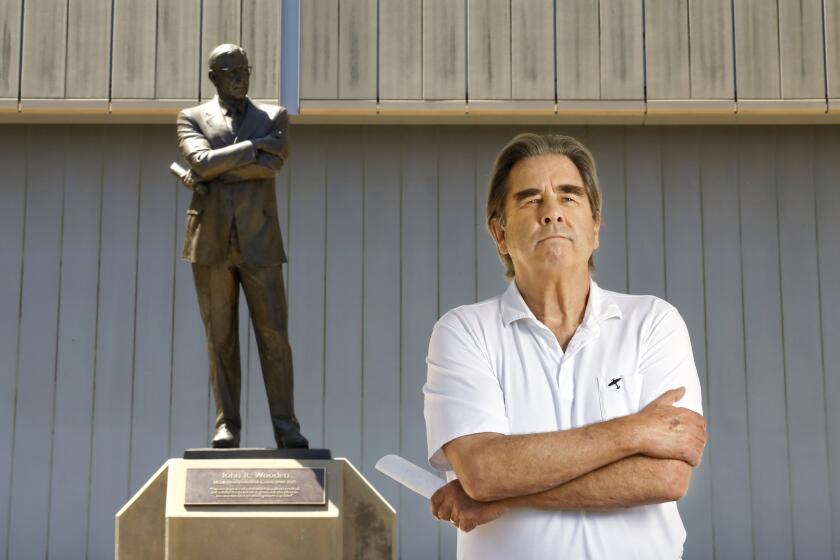

Beau Bridges recalls trying out for the team, embracing John Wooden’s Pyramid of Success and portraying his “funny as hell” mentor in a one-man play.

Coen first tried to get it to work with a 2005 radio play with his brother. He then wrote a trio of three-act plays: “Almost an Evening” (2008), “Offices” (2009) and “Happy Hour” (2011). All were directed by Neil Pepe and unveiled at New York’s Atlantic Theater Company, where Pepe is artistic director and where “A Play Is a Poem” will run next year.

Another of Coen’s one-acts played on Broadway alongside pieces by Elaine May and Woody Allen under the title “Relatively Speaking.”

“That was terrifying. It was 1,000 seats, and I was the youngest person there — that’s a problem,” Coen said, laughing. “It was me, Woody Allen and Elaine May. It did well for a while, because they’re all old Jews, but then we ran out of Jews and then it was just tourists and they weren’t buying that [stuff]. They were just having none of it!”

He opted to debut “A Play Is a Poem” in Los Angeles as a new challenge.

“It’s actually been a pleasant surprise,” said Coen, who stays in Santa Monica when filming in the area. “I’ve never done a play here and I had no idea who goes to theater here, but the audiences have been pretty good so far.

“You know, me and Joel — it’s a strange phenomenon, it happens a lot, where you think the movies are pretty funny, or at least more or less work, and the studio does too, and then you show it to a big audience and people are puzzled.

“Pretty much the exact same thing has happened with my plays, frequently, where you and the actors and Neil think, ‘This will kill,’ and then the audience is just flummoxed. ... And that has not happened, weirdly.”

Though he and Joel famously avoid watching their movies after making them, Ethan plans to check in on “A Play Is a Poem” often, “because I just don’t want to say goodbye to the actors yet.”

He also will sit through Saturday’s opening night, a performance that usually makes him nervous.

“I’ve been weirdly relaxed about this one,” he said. “It’s amazing, I’ve been like a Zen monk in a way, my brainwave is almost totally flat. Everything I was apprehensive about has turned out to be kind of great.”

Fall theater season highlights for Los Angeles include a musical version of “Almost Famous,” Bill Irwin in “On Beckett,” a revival of August Wilson’s “Jitney” and a new stand-up show by comic Mike Birbiglia.

And though we’ve talked about the play for an hour — summarized it, dissected it, explored the spaces around it — our thoughts and conversation about the play are not the same as watching the play itself and experiencing its indescribable theatricality. This is what the title “A Play Is A Poem” means, Coen concluded.

He suddenly sat up to elaborate. “It’s like, if you synopsize the story, you haven’t really described the play. It’s about something other than that, and the ‘something other than that’ is the thing.”

Though Coen has directed dozens of movies, he won’t helm a play anytime soon. “I can see it all, nothing’s done behind a curtain, and yet I don’t quite know how he does it,” he said of Pepe. And Coen will write a musical only “if somebody else will do all the music, sure.”

But he is already months into the writing of his next play. “It’s longer than most of these, but I don’t know if it’s a full-length thing,” he said. “It’s uncategorizable in terms of length. Pain in the ass, in that regard.”

'A Play Is a Poem'

Where: Mark Taper Forum, 135 N. Grand Ave., L.A.

When: Opens Saturday. Performances at 8 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays, 2:30 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 1 and 6:30 p.m. Sundays; through Oct. 13. (Check for exceptions.)

Tickets: $25-$99 (subject to change)

Info: (213) 628-2772 or centertheatregroup.org

Running time: 1 hour, 45 minutes

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.