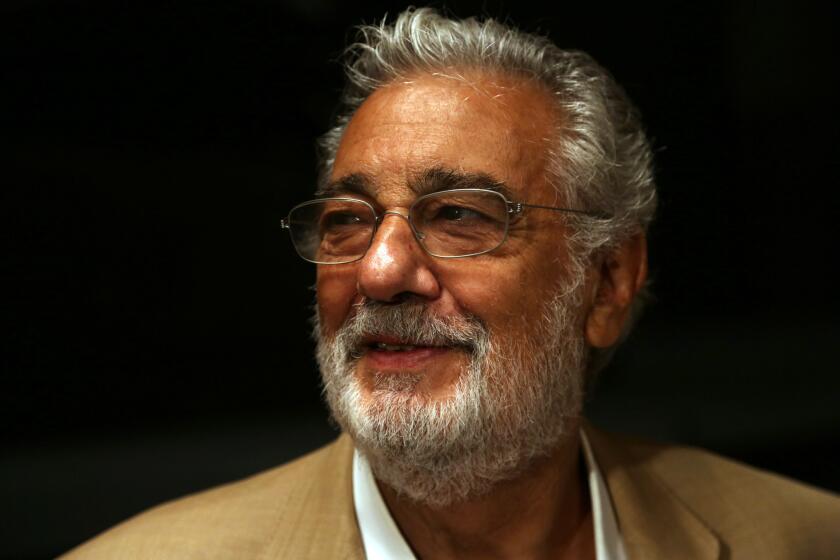

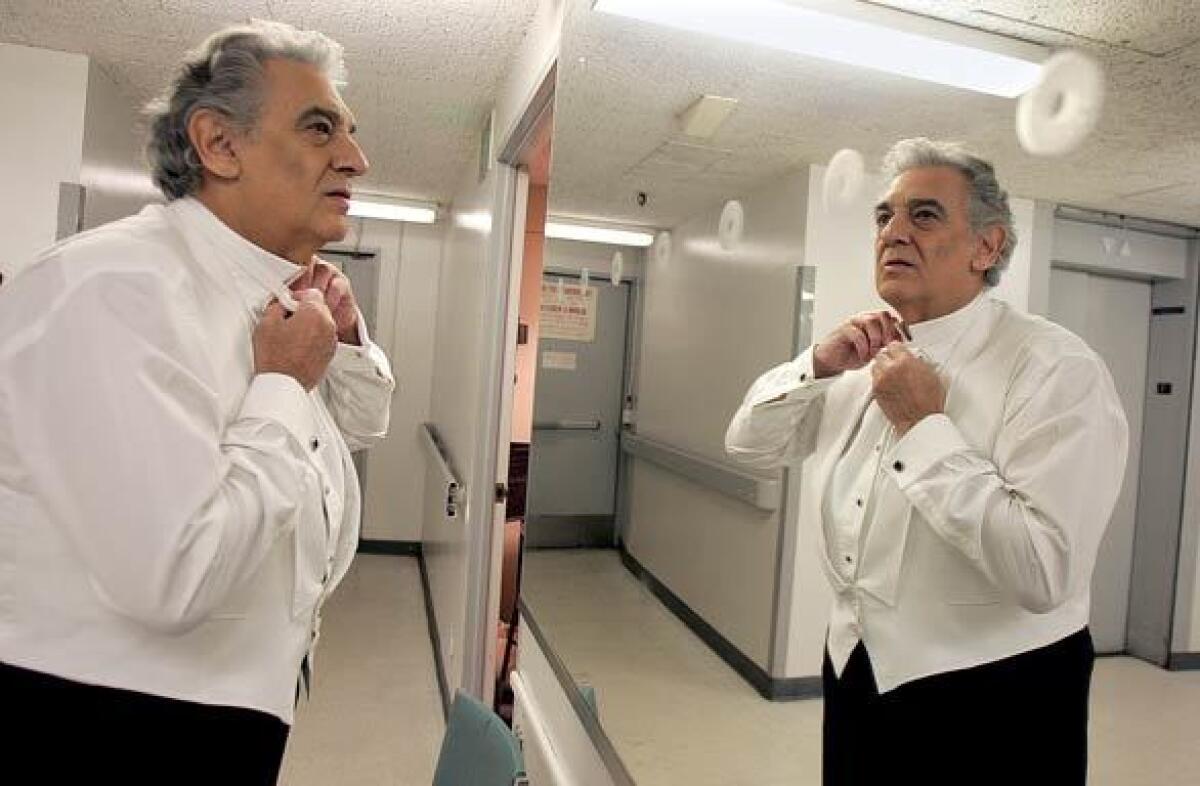

Plácido Domingo faces new sexual harassment reports, and pressure on L.A. Opera grows

As Plácido Domingo faced a second round of sexual harassment allegations Thursday, pressure mounted on Los Angeles Opera to take action against its general manager, and opera-world support for the singing legend began to wither.

Eleven more women told the Associated Press that they were subjects of unwanted touching, persistent requests for private meetings, late-night phone calls and kisses by Domingo. The new allegations follow an Aug. 13 AP article in which nine women accused Domingo of sexual harassment and in some instances damaged careers when the women rejected his advances.

Following the newest accusations, sources close to L.A. Opera operations told The Times on Thursday that Domingo is not involved in day-to-day management while a company investigation remains underway. But with the number of alleged victims hitting 20 and a new, named accuser providing compelling corroboration for her story, L.A. Opera faced growing calls to take more aggressive steps.

Domingo’s personal spokeswoman, Nancy Seltzer, told the AP: “The ongoing campaign by the AP to denigrate Plácido Domingo is not only inaccurate but unethical. These new claims are riddled with inconsistencies and, as with the first story, in many ways, simply incorrect. Due to an ongoing investigation, we will not comment on specifics, but we strongly dispute the misleading picture that the AP is attempting to paint of Mr. Domingo.”

Seltzer declined The Times’ request for further comment.

Los Angeles Opera issued a statement that said it takes the allegations “extremely seriously.”

“We believe all our employees and artists should feel valued, supported and safe. We are, however, unable to discuss any specific claim,” the company said, declining further comment until the completion of work by its investigator, the law firm of Gibson, Dunn and Crutcher.

The new AP report, which cites 10 anonymous accusers, largely focused on the detailed accounts of singer Angela Turner Wilson during the 1999-2000 season of Washington Opera, where Domingo was artistic director.

Wilson told the AP that she, then 28, and Domingo were having their makeup done together when he rose from his chair, stood behind her, slipped his hands into her robe and under her bra straps, and grabbed her bare breast.

“It hurt,” she told the AP. “It was not gentle. He groped me hard.” She said Domingo then turned and walked away, leaving her stunned and humiliated.

Accusations of harassment against Plácido Domingo dating back to the 1980s raise many questions, and generate a statement of denial from the opera legend.

Wilson said she was spurred to come forward after Domingo responded to the first AP articleby saying he believed his actions “were always welcomed and consensual” and added: “The rules and standards by which we are — and should be — measured against today are very different than they were in the past.”

Wilson rejected the idea that such behavior has ever been acceptable.

“What woman would ever want him to grab their breast? And it hurt,” she told AP. “Then I had to go onstage and act like I was in love with him.”

On Thursday The Times reached Wilson, a college voice teacher in the Dallas area, but she declined to discuss her experience further.

Wilson was the only new accuser to speak to the AP on the record. The others requested anonymity because they still work in the industry and said they feared recriminations in a world long dominated by Domingo and other powerful men.

The AP reported that some women said vocal support for Domingo in Europe — and skepticism of the women’s accusations — has made them fearful of coming forward publicly.

Despite the accusations he faces in America, or perhaps because of them, Plácido Domingo is lavished with cheers at the Salzburg Festival in Austria.

Indeed, global opera star Anna Netrebko and singer Sonya Yoncheva, the 2010 winner of Domingo’s Operalia competition for emerging talent, were quick to defend Domingo last month.

The Times talked with several sources connected to L.A. Opera’s past productions over the years who challenged the veracity of the first anonymous AP accounts and recalled different scenarios — ones in which young women, fans and performers alike, sought to establish a relationship with the opera star. Behavior behind closed doors remained unknown, but the sources, who demanded anonymity because they feared not only professional reprisals but also attacks from the #MeToo movement, said they never witnessed the kind of predatory behavior reported by AP.

By Thursday, however, as the second wave of allegations hit, some of those defenders privately expressed less confidence in Domingo’s innocence or were conspicuously quiet.

The Metropolitan Opera in New York, where Domingo is scheduled to sing in “Macbeth” later this month, on Thursday reiterated its previous statement withholding judgment until the results of L.A. Opera’s investigation are in.

Pressure for the results of that inquiry is peaking. L.A. Opera’s season will open with “La Bohème” on Sept. 14. Sources close to the company said Domingo is not scheduled to be in L.A. until the investigation concludes. While some speculate that his absence from the city could encourage more voices within L.A. Opera to speak out during the investigation, skeptics see the move as crisis management — an effort to avoid provoking victims’ advocates and stoking a protest on opening night.

Meanwhile, the hashtag #Opera9 being used on Twitter changed on Thursday to #Opera20 based on the new count of alleged victims. Those using the hashtag, including women and men working in opera, said they had been silent for too long and that the problem of sexual harassment in the opera world is an open secret.

The two singers who spoke on the record to the AP, Wilson and Patricia Wulf, both recounted their experiences while working for what is now Washington National Opera at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. On Thursday, Kennedy Center President Deborah F. Rutter and Washington National Opera General Director Timothy O’Leary responded to a broader implication in the AP articles: that improper behavior was regularly ignored by management.

Rutter and O’Leary cited “zero tolerance policies with regard to harassment and discrimination” and said, “The Kennedy Center did not receive any documented complaints about Mr. Domingo’s behavior prior to WNO’s affiliation with the Kennedy Center in 2011, and has not received any since.”

The AP cited former L.A. Opera employees who accused company administrators of disregarding harassment here.

The AP article quoted Melinda McLain, a production coordinator for the 1986-87 season, saying she had to create elaborate schemes to keep Domingo away from particular singers. McLain said another strategy was to invite Domingo’s wife, Marta, to attend company parties, “because if Marta was around, he behaves.”

One anonymous employee told the AP that she was instructed not to send attractive young women into costume fittings with Domingo because of his reputation for “getting too close, hugging, kissing, touching and being physically affectionate.” A different costume employee recalled having to dodge a kiss so it landed on her cheek and not her mouth. Another staffer told the AP that Domingo backed her against a wall, grasped her hand and whispered in her ear while her male boss looked on.

L.A. Opera and its investigator declined to define the scope of the current inquiry and whether it includes the alleged failure of management to respond to harassment. L.A. Opera board Chairman Marc Stern declined The Times’ request for comment.

Wilson told the AP she was aware of Domingo’s reputation by her third season at Washington Opera but wanted to believe his interest was professional. Over time there were frequent invitations, Wilson said, to come to his apartment to watch a video of a role he wanted her to sing, or to go to dinner.

“I would say, ‘No, maestro.’ I said that a lot. I felt like if I put ‘maestro’ on it, it would still be respectful,” she told the AP.

“I stuck to no — No, I won’t meet you. No, I won’t go with you upstairs to your apartment. No, no, no.”

Wilson said one day she was scheduled to have her makeup done alongside Domingo, which she “thought was strange. ... Usually, big stars, especially headliners, get their makeup done in their dressing room.” But she said was reassured by the fact that the makeup person was also present and the door to the room was open.

Wilson said that after he grabbed her breast, she cried out in pain and asked the makeup person, “Did you see that?” Reached by the AP, the makeup artist said he did not recall the incident.

She said she called her husband and her parents that night — and also the night Domingo tried to kiss her — and all three confirmed to the AP that she was upset and in tears when she related to them what happened.

Wilson provided the AP with copies of a journal she kept at the time that notes rehearsals for the production, “Le Cid,” began Oct. 4, 1999. In an entry a month later, she wrote that Domingo “has told me several times how happy he was with my singing “ but also “he hits on me all the time.” She added, “Please God don’t let it get any worse.”

The next season, she said, she had three roles but Domingo barely acknowledged her.

Though she won the company’s prestigious Artist of the Year award that season, in 2000, Wilson told the AP that the Washington Opera never again hired her, which she attributes to her interactions with Domingo.

Her career lasted a decade longer before she switched mainly to teaching.

Wilson said she realizes it’s hard for many among his legions of admirers to come to terms with stories accusing him of sexually aggressive actions.

“It would be hard as a fan to justify or rationalize how somebody so charming and generous in so many ways could be this person,” she said.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.