History forgot these female composers. An L.A. music writer is helping us remember

American composer Anita Owen wrote her biggest hit song, “Sweet Bunch of Daisies,” in 1894. She was 20 at the time, a student at a convent outside Terre Haute, Ind.

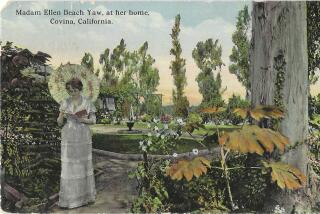

According to a 1910 article on female composers in the San Francisco Call, Owen self-published the song for less than $50. That investment paid off when the song became a hit, selling more than a million copies. According to the San Francisco Call, a “practically penniless convent girl” was transformed into a woman with “fame and fortune” whose bank account “fell only a little short of the hundred-thousand-dollar mark.”

If you’ve never heard of Owen or any of the 200-plus songs she composed during her successful career, you’re not alone.

“I don’t want to call it a conspiracy, because I don’t think it’s done on purpose, but there is this falling away of women artists and artists of color that needs to stop and be corrected,” says composer Laura Karpman.

History may have forgotten many of them, she says, but women and people of color have always composed music.

In what she calls a “small little act of course correction,” Karpman is premiering an overture Thursday night at the Hollywood Bowl that incorporates melodic snippets from patriotic songs by Owen and two other early 20th century American female composers, Mildred Hill and Emily Wood Bower.

The new orchestral piece, commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic and titled “All American,” features percussion instruments crafted out of kitchen tools like baking sheets and meat tenderizers, a nod to the domestic work that historically defined so many women’s lives.

Karpman describes “All American” as big, bold, brash, percussive and propulsive. The traditional sounds of American patriotism are there — brassy fanfares and marching band-style percussion — but they’ve been filtered through a feminist lens.

“It’s about amplifying women,” the composer says. “It’s about wanting to be out loud myself, but it’s also about saying, ‘And here are my sisters. They didn’t get this opportunity.’ ”

A Juilliard graduate who studied with Milton Babbitt and Nadia Boulanger, Karpman, 60, is a film and television composer who also writes for the concert hall and opera stage. She lives in Playa del Rey with her wife, composer Nora Kroll-Rosenbaum, and their 8-year-old son. The couple have transformed the downstairs of their beachfront home into an instrument-filled musician’s paradise, complete with a Steinway grand piano, soundproof recording studio and writing space for each composer. On a shelf across from her workstation, Karpman’s four Emmys mingle with other shiny awards.

Karpman often wears two pairs of glasses — a fashionable oversized pair on her face, and a colorful pair of reading glasses perched atop her head. It’s become a signature look, practical accessories that add to the sense that she is constantly in a state of creating, thinking or preparing to create. (“She writes music every day. Every single day. It’s what she does,” Kroll-Rosenbaum says.)

Sitting on the shaded patio just off her home studio, both sets of eyeglasses in place, Karpman discusses the origin of “All American.” The L.A. Phil commissioned her to write an overture for an all-American program at the Bowl that includes music by Charles Ives, Samuel Barber and Duke Ellington.

“Great! We’ll call it ‘All American’ and I’ll figure out what to write later,” Karpman recalls responding.

That title served as a starting point for the composer, who says she often deals with themes of patriotism in her concert music.

“I always try to write something that has some reflection of social justice or some reflection on how I’m feeling about patriotism at any given moment,” Karpman says.

In this particularly divisive moment for our country, Karpman says she thinks of America as a promise: “It’s an ideal. It’s a dream. It’s a dream that is not at all accomplished, and maybe hasn’t really even started. But it’s a dream that I have, and it’s a dream that a lot of other people have, and we have to hold on to it.”

With patriotism in mind, Karpman’s initial compositional impulse was to “take some Souza and flip it upside down, do something funky, have some fun with it.”

And then she stopped herself: “Wait, what am I doing? Where are the women?”

Karpman is passionate about increasing opportunities for female composers in film, television and classical music. Her lifelong interest in the subject turned to action after she saw research by Martha M. Lauzen, a San Diego State University professor and founder of the Center for the Study of Women in Television & Film.

“Numbers don’t lie and they don’t whine. They just exist. And they’re terribly shocking,” Karpman says.

Inspired to act, Karpman co-founded the Alliance for Women Film Composers in 2014. In 2016, she became the first woman elected to the board of governors in the music branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

And so, after that initial impulse to look to Souza for inspiration, she followed her own advice and switched course, searching for female composers of patriotic music from whom she could draw inspiration. She also added italics to the “All” in her title to emphasize inclusivity.

Just two months after his operation and start of chemo, the British conductor carries on — in fine style.

Karpman found more patriotic songs by women than she expected. She discovered Owen, who wrote “’Neath the Flag of the Red, White and Blue” in 1893, just a year before composing her hit, “Sweet Bunch of Daisies.”

She also came across Hill, the woman who, along with her sister, composed the tune to “Happy Birthday,” the most ubiquitous song in the English language. The upward gesture of a phrase from Hill’s “March On, Brave Lads, March On!” is snagged and reframed in “All American” as the starting point for a new, more modern melody.

Bower’s “Your Country Needs You” was another of Karpman’s discoveries. Bower’s piece contains the line, “Your country she needs you at the front, her call rings loud and clear.” Including that line in her overture is subversive, Karpman says, because she is thinking of a different sort of “front” than perhaps Bower was referencing.

Karpman’s own call to action is clear. She wants to counter the “pervasive invisibility” of women like Owen, Hill and Bower, to reveal their history so that women composing today will know “that we have shoulders to stand on, that we always have.”

Karpman has dreams for launching a sort of musicological Marshall Project some day that would catalog, record and publish forgotten music by female composers from around the world.

In the meantime, she’s using her art as an engine for change.

“Even if it’s a little snippet, even if it’s coming through my filter, these composers will be heard at the Bowl,” she says. “But guess what? Their music deserves to be heard on its own too.”

She encourages other women to take up the same kind of cause. “Let’s find our sisters from the past and see how we can amplify their work.”

'All American'

What: L.A. Phil performing Karpman’s premiere on a program that includes Copland’s “Appalachian Spring”

Where: Hollywood Bowl, 2301 N. Highland Ave., L.A.

When: 8 p.m. Thursday

Tickets: $8-$135

Info: hollywoodbowl.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.