How Playbills became social media must-shares

Uzo Aduba enters the theater minutes before a matinee of “Be More Chill.” An usher directs her to her seat, she sits down and silences the ringer on her phone. But before she puts it away in her purse, she discreetly holds up her Playbill with one hand and snaps pictures.

The still-life Playbill photo shoot has become a routine scene on Broadway and beyond — a preshow ritual that has theater fans posting the photos to social media, flooding the feeds of families and friends.

“I don’t even know how I started doing it,” the Emmy-winning “Orange Is the New Black” actress told The Times. “Maybe it was back when we were still Facebooking and in early-stage Instagram. It feels like I’ve just always done it.”

A photo of a show’s Playbill — the free program that doubles as a performing arts magazine — has become a nearly universal way to digitally commemorate an occasion of theatergoing.

Score tickets to a sold-out show, after months of waiting and saving? Celebrating a special occasion with a night out? Won the production’s lottery for cheap seats? As with any other humblebrag on social media, the Playbill post punctuates the experience. Even theater journalists who receive complimentary tickets to shows participate, whether to inform readers of what’s on the horizon or to boast to one another about their proximity to the stage.

“I honestly think it’s a bit of a status-symbol thing — it makes me seem cool and cultured, even if I’m not exactly rocking the boat and checking out the most adventurous or experimental theater,” said Vox critic-at-large Emily VanDerWerff, 38, who sees shows in Los Angeles and New York and posts Playbill pictures on Twitter. For those who are buying their tickets, she added, “I suppose there’s a whole class thing involved too: I have enough money to afford theater tickets, and here’s a way to low-key brag about it.”

Among regular theatergoers, it’s the online way to showcase the free souvenir. A post on a Facebook wall is a virtual version of a picture frame, and a Playbill-filled Instagram grid is a digitized collection that in an earlier era would have been kept only in boxes or binders.

“I don’t do it for likes — I couldn’t care less — because it’s more for me, a documentation so I don’t have to go back into my box of Playbills to remember what I’ve seen,” says Kelley Blosser, 32, who works in real estate in New York and was one of dozens of theater fans whom The Times interviewed for this story.

In many ways, Playbills emerged as social media stars out of necessity. It’s the best way to share a live experience that, unlike concerts and sports events, largely outlaws photos.

Though venues are decorated with signs and posters, “With the lights and busyness around the front of the theater, it’s not always possible to get a good shot, especially when you need to get in a long box-office queue to pick up your tickets before the show,” said Fiona Scott, 26, a graduate student in England.

Besides, “Anyone can post a picture with a marquee, whether they’ve seen the show or not, but the physical Playbill proves that you were actually part of the audience,” noted Jamie Rogers, 26, a television news director in Wisconsin.

Another reason Playbill pics are preferred over selfies and posed photos: the low, and notoriously unflattering, house lights. “And usually, I’m running to shows after work and I don’t look super glam,” said Michelle Owens, 24, an actress who sees theater in New York and Chicago.

It’s somewhat gauche to post a photo of one’s ticket, as the price is printed clearly, and a generic show curtain or an unfamiliar set doesn’t say enough. Playbills, on the other hand, showcase the name of the production and theater prominently. Even at theaters that don’t use Playbills but distribute other publications — think Performing Arts or Footlights in Southern California, or souvenir programs at West End theaters — the practice is much the same.

“It’s just easy. It’s right there. You don’t need to pose,” noted New York Times culture reporter Sopan Deb, 31. “The Playbill photo is the ultimate combination of laziness and vanity.”

It’s difficult to pinpoint when the phenomenon began. The 135-year-old company prints 3.5 million Playbills per month and distributes them not only among New York’s Broadway and off-Broadway sites but also at venues hosting touring productions (like the Hollywood Pantages), regional theaters (such as the Geffen Playhouse in Westwood) and even schools with student productions.

The signature layout, featuring a yellow banner above the show’s key art, dates to the 1950s and is so widely recognized that it inspired screenwriter Gary King’s 2002 wedding program. “It was a big hit,” recalls King, now in his 40s. “It had the biographies and credits of everyone in the wedding party, just like the actors do.”

Still, the company doesn’t take credit for plotting Playbills’ online prevalence.

“Were we so strategic? Nope!” Philip S. Birsh, Playbill president and chief executive, said with a laugh. “The shows are, like a lot of things in the world, fleeting: You enjoy it, and it’s gone. And what fans have left is this official piece of evidence, this thing that says ‘I was there.’ We love that they’re posting these photos to share that.”

On Instagram, the most common hashtag for Playbill posts is #TonightsBill, which first appeared in August 2016, the platform said. According to Instagram, this hashtag has been used most often in theater-filled cities such as New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and London.

This kind of word-of-mouth endorsement is what companies dream about, according to Ari Lightman, professor of digital media and marketing at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College.

“Brands are trying to figure out how to encourage this kind of promotion — for example, major hotel chains work with travel influencers or food bloggers to capture the essence of their locations — but most of the time, they’re paying for it,” he said. “In this case, it really is happening quite organically.”

Theater producers and advertising agencies are taking note of the trend, and creating their Playbill covers accordingly. Social media promotion has become a top consideration when finalizing a production’s iconographic imagery and signature look.

“In the days before social media, if it looks good on a marquee and in a print ad, it was good enough,” said Stacey Lieberman Prince, vice president and executive creative director of the advertising and branding firm SpotCo. “Now, it’s all about being flexible in terms of scale. It has to work well on a Times Square billboard as well as a tiny social post on Instagram.”

Plays, especially those with limited runs, showcase the star power of a lead actor, mirroring the posters of a blockbuster movie or TV show. But in recent years, producers of musicals — which generally eye open-ended runs — have doubled down on abstract designs that not only outlast their casts but also stand out against the covers of all previous seasons. “Hadestown” — which went on to win eight Tony awards, including best musical — is one of them.

“You want to get to a point where someone can see the symbol without the title of the show and already know what it is, because it’s so unique,” said “Hadestown” producer Mara Isaacs. “When you see the star, you know it’s ‘Hamilton.’ Those eyes, it’s ‘Cats.’ Certain shows have found that a simple visual gesture goes far.”

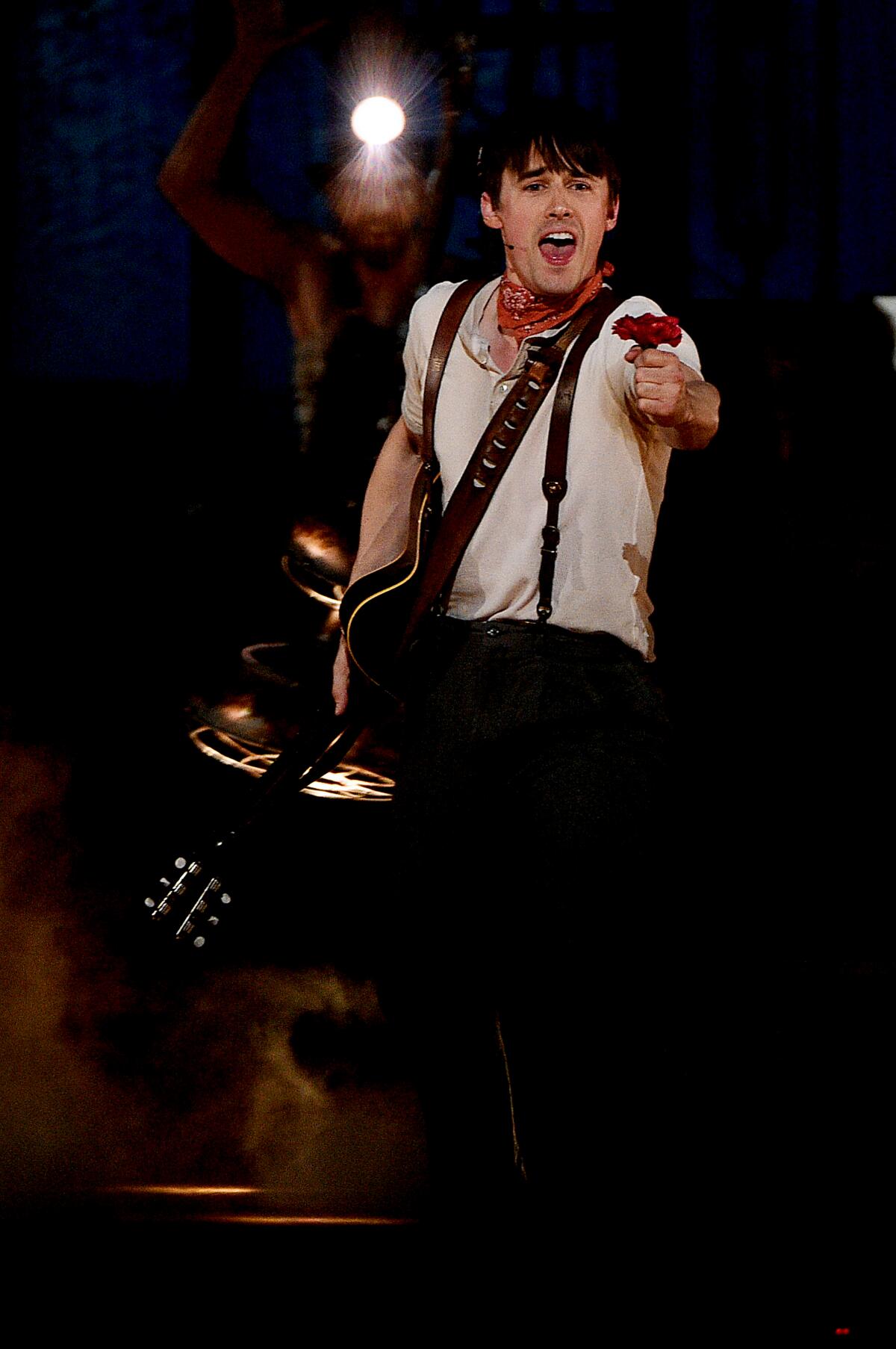

Isaacs worked with SpotCo to derive key art that zoomed in on a specific image from the show. After many drafts featuring trains, trees and trumpets — designs that SpotCo shared exclusively with The Times here — the strategy returned to the red flower, featured on the Grammy-nominated cover of the 2010 concept album (and tattooed on the arm of creator Anais Mitchell). The Playbill now features gritty, industrial fog and a brave hand holding a bright red ranunculus (though ‘Hadestown’ fans call it a poppy).

The marketing decision prompted director Rachel Chavkin to integrate the flower into the show more often and spurred the show to distribute them to the audience after performances.

“It was important to me that anyone looking at the key art could see themselves in it, regardless of gender and age, because I didn’t want anyone to feel left out by showing who was in it,” Isaacs said. “It really took off! Now they’re popping up in all kinds of places, like fan art and graduation caps.”

Though Playbill photos are plentiful online, they’re not exactly that easy to take. Talk to enough theatergoers, and you’ll soon have a list of unofficial best practices.

First, there’s the taking of the photo. Take the photo from your seat, as it’s poor form to walk through the theater for a spot closer to the stage. Hold your program fairly far in front of you, and at a rakish angle, said San Francisco Chronicle theater critic Lily Janiak, 33. “It makes the picture more visually interesting — otherwise you have too many right angles all in a line, especially if there’s a proscenium stage.”

When positioning the program, “I discreetly try to get as much of the set in the shot, even when ushers say not to, while also using the Playbill to block whatever heads are in front of me,” Blosser said.

Feel free to include your thumb holding the program, said Maggie Gilroy, 26, a reporter for the Binghamton Press & Sun-Bulletin in New York State. “If my nails are done, I’ll include it — and sometimes, if I know I’m going to a show, I’ll get my nails done beforehand.”

For the love of God, tap the camera’s focus on the Playbill instead of the stage, reminded Maya Banitt, 22, who works with a virtual reality startup in Seoul, South Korea. “It’s OK for the background to be blurry because it looks artsy,” she said. “What’s important is that we can read what’s on the front of that Playbill.”

Don’t let the house’s dim, warm lights prevent you from getting the shot you want. “Make sure the brightness of your phone screen is all the way up so you can see if there’s too much exposure,” suggested Lennon Tobey, 16, a student in Trinity, Fla.

Different locales might require extra steps. In London, a phone camera’s night settings are best, “as older Victorian theaters are quite dark,” said chartered accountant Sophie Hamlet, 32. Rukaya César, 25, a social media marketer, makes the shoot a team effort: “One person uses the flashlight on their phone to light the [program], while another takes the photo on our phone. It makes the photo look better without having to use direct camera flash.” (That’s another faux pas: A flash will bounce off the cover’s glossy finish.)

Then, there’s the publishing of the photo. Some prefer the fleeting glee of Snapchat or Instagram Stories; others love to cement the memory on their Instagram or Facebook profiles.

“My feed would become a grid of programs if I posted on Instagram every time I was at a show,” said Scott. Added Erica Bahrenburg, 25, who works in publicity in New York: “If it’s a show I’m seeing for a second time, chances are I won’t post about it.”

Sometimes, a specific show requires both. “The thing I’ve seen is, if you’ve gone to see something, maybe it might exist on your IG story, and if you’re super into it and want to show a real intense passion, it gets a post on your feed,” Aduba explained. “It’s case by case, but I’ve noticed that trend, if there’s something more personal to the experience and you want to make it stand out a bit more by writing something about it in the caption.”

Like any online post, the comments section is a place for conversation, and that caption kicks it all off. Some patrons, like Whitney McIntosh, 27, an editor in Brooklyn, publish their post after watching the production, including their opinion within a few sentences. “That way, other people who have seen the show or are interested in it will talk about it and discuss what they thought [in the comments].”

Others, like Katherine Welsh, 36, a taxonomist in Nashua, N.H., prefer to post the photo on Facebook and Instagram with a light, brief caption “while I’m waiting for the show to start, so I don’t know if I like it yet. I might put a little review in the comments later, especially if people ask how it was.” (A few, like podcast co-host Emily Brandwin, will make a key decision after the final bow: “If a show is a real dud, I won’t post.”)

Unlike TV and film fans sharing their thoughts on Twitter and Facebook, theatergoers posting Playbill photos don’t always tag the production’s social media accounts or the show’s preferred hashtags. “I kind of like keeping things private,” said Gillian Kane, 31, an office coordinator in Sylmar. “I’d rather only people I know have that information than anyone on Instagram and the creative teams behind the shows.”

It’s true: Theatermakers do scroll through social media to see fans’ Playbill photos.

“I feel elated every time,” said “Broadway Bounty Hunter” co-producer Maxwell Haddad, 32. “To me, it means that they care enough to share with their followers that they’re seeing the show.”

Before “Tootsie” performances, Tony-nominated actress Sarah Stiles catches posts published in real time by those who are about to watch her onstage.

“I actually love it when you can see the Playbill and the stage in their picture, because when I’m up onstage that night, I totally clock it,” she said. “I know exactly where that person is sitting, and how excited they are to be there. To feel the audience’s excitement so immediately — that’s what every performer wants.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.