Essential Arts: The demolition of Tokyo’s legendary Nakagin Capsule Tower begins

It is getting warmer and I’ve been finding myself obsessed with mangonadas. The fresh ones are great, but I’m just as happy eating the frozen ones by Frutifresca I find at my local mercadito. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, arts and design columnist at the Los Angeles Times, with your weekly culture newsletter and essential frozen foods:

Sayonara, Nakagin

One of the great experiments in architecture is being demolished as I write this.

The Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo, designed by architect Kisho Kurokawa (1934-2007) and completed in 1972, is perhaps the most iconic example of Japanese Metabolism, a 20th century movement that sought to create an architecture that was organic in nature: one that could be expanded and rearranged according to need, that could be endlessly customized. After decades of decay, and years of inhabiting a limbo on whether it might be preserved, demolition began Tuesday.

The word “iconic” gets tossed around a lot in descriptions of architecture. But Nakagin truly fit the bill: a building that became a symbol of architecture’s most idealist tendencies and of Tokyo itself.

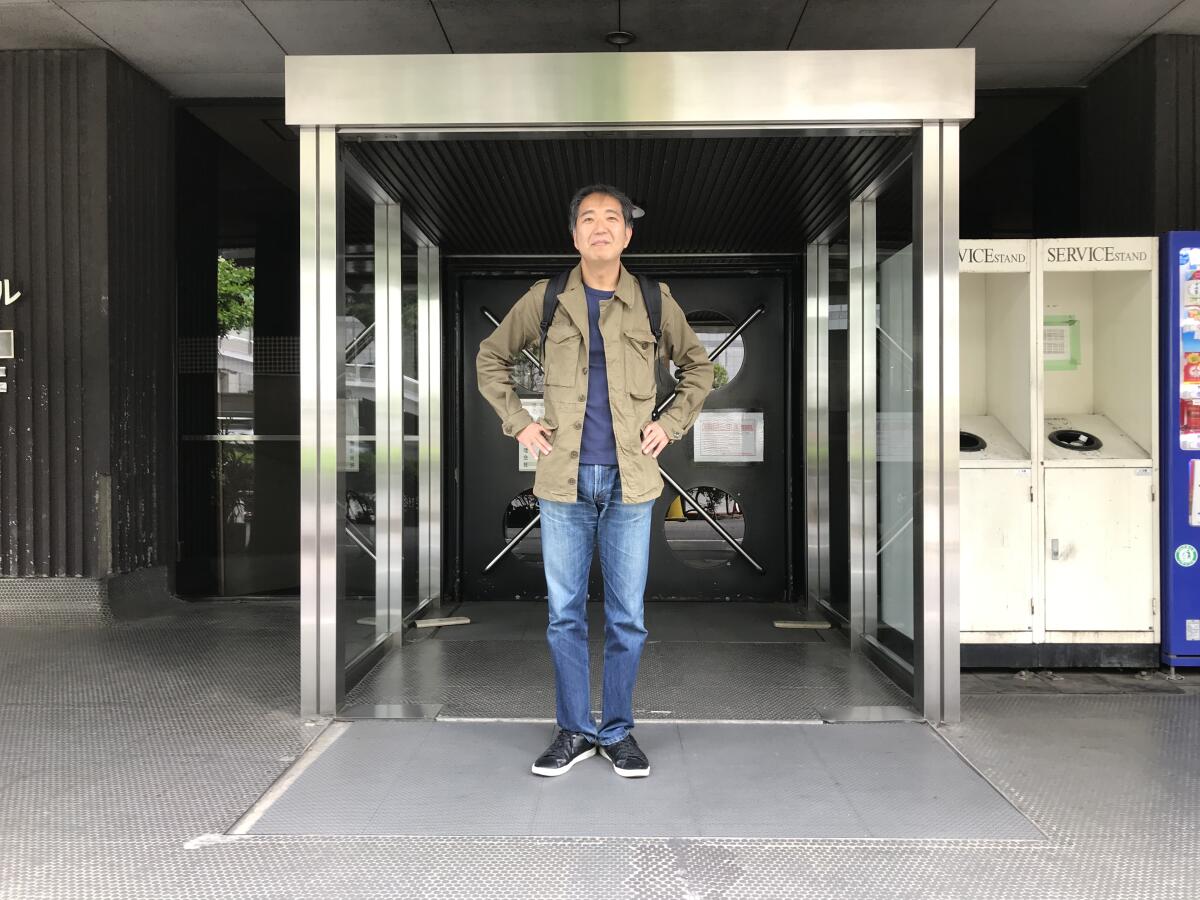

In 2019, I had the good fortune to see the Nakagin Capsule Tower in person, not just from the outside but inside too.

At that point, the building’s future had already been in question for years — aggravated by neglect and the 2008 recession — and preservationist Tatsuyuki Maeda was leading a valiant battle to have it preserved. Maeda had not only acquired 15 of the capsules but had also helped establish the Nakagin Capsule Tower Building Preservation and Regeneration Project, a group that tried to seek protected status for the building, including a possible heritage designation from UNESCO.

But the pandemic got in the way. Maeda had planned an architectural conference to further draw attention to the tower and perhaps find a preservation-minded buyer for the building. COVID-19, however, put an end to that. Last year, the building, wrapped in mesh, its concrete core bearing evidence of continuous leaks, was sold to a developer who prepared to raze it.

The tower was composed of a concrete service core, onto which 140 prefabricated pods were attached — each of which consisted of a 104-square-foot room with a bathroom included. The pods, geared at salarymen who needed a place to crash for the night while in Tokyo, were intended to be replaced every 25 years. But the building’s design made that impractical. (To remove a capsule from the bottom required removing those above it.)

Time and economics also took their toll. Capsules went without upgrades. Water permeated the core. The building took on the aspect of sci-fi relic.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox once a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

It is now too late to save the Nakagin Capsule Tower, but it’s not too late to consider its underlying concepts: a flexible architecture that could be made more resilient through continuous piecemeal upgrades rather than requiring demolition and reconstruction.

The latest (terrifying) report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is critical of the role of architecture — specifically, wasteful new construction — in fueling climate change. Efforts to reuse the buildings we already have will be critical to reducing carbon emissions.

Kurokawa offered another model. Perhaps, it’s time to revisit it.

In the vitrine

I’ll have what Barbara Isenberg is having. The Times contributor is reporting on a new show at the Skirball Cultural Center that is all about the history of the Jewish deli. “The story of American cuisine is the story of immigrant adaptation,” scholar and curator Lara Rabinovitch tells Isenberg. “The Jewish deli within that narrative is a restaurant culture brought here from Eastern and Central Europe and expanded to become mainstream in American life.” I could now use some pastrami and a chocolate egg cream.

At LACMA, the exhibition “City of Cinema: Paris 1850-1907,” which was jointly curated by the museum with the Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, aims to capture life in late 19th century Paris, the milieu that gave birth to film. But Times art critic Christopher Knight isn’t impressed with the framing. He cites an introductory wall text that reads: “This exhibition traces film’s evolution from a disposable entertainment to the twentieth century’s greatest art form.” Knight is not buying: “A great movie is a great movie,” he writes, “a great painting is a great painting. Period.”

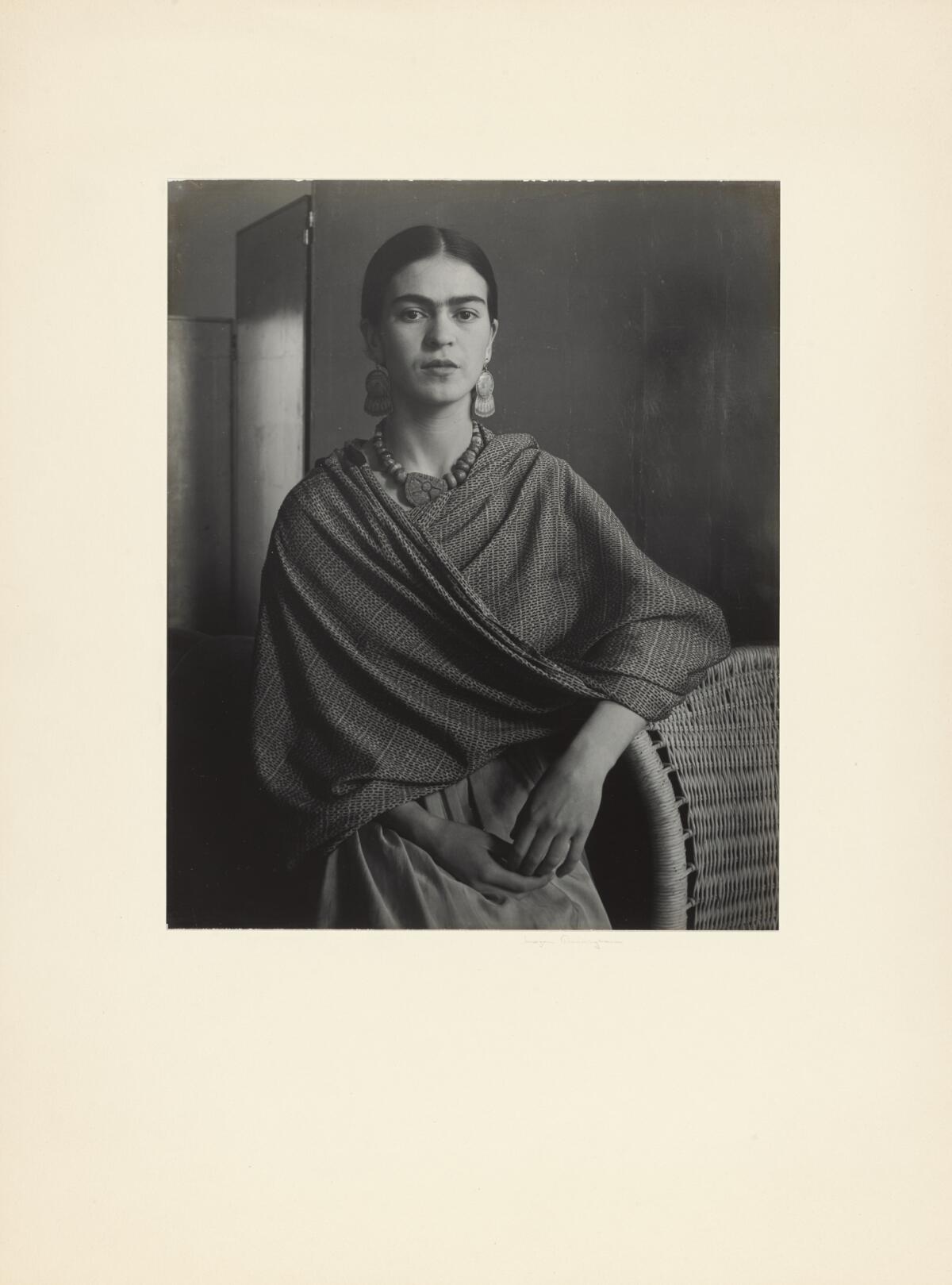

Knight also reviews a show of photography by Imogen Cunningham at the Getty Museum — the first thorough survey of the artist’s work in more than 35 years. “Intimacy characterizes her best portraits, nudes, still lifes, rural and industrial landscapes, street photographs — even an ethereal 1910 view of the iconic fountain in London’s Trafalgar Square,” he writes. “Backlighted by the sun, the tiered fountain of splashing light is a virtual silhouette that fronts the classical base of the famous column to Lord Nelson, hero of a naval victory in the Napoleonic Wars. The lower third of the composition is all water, as if the artist (and, by extension, the viewer) were wading out in it.”

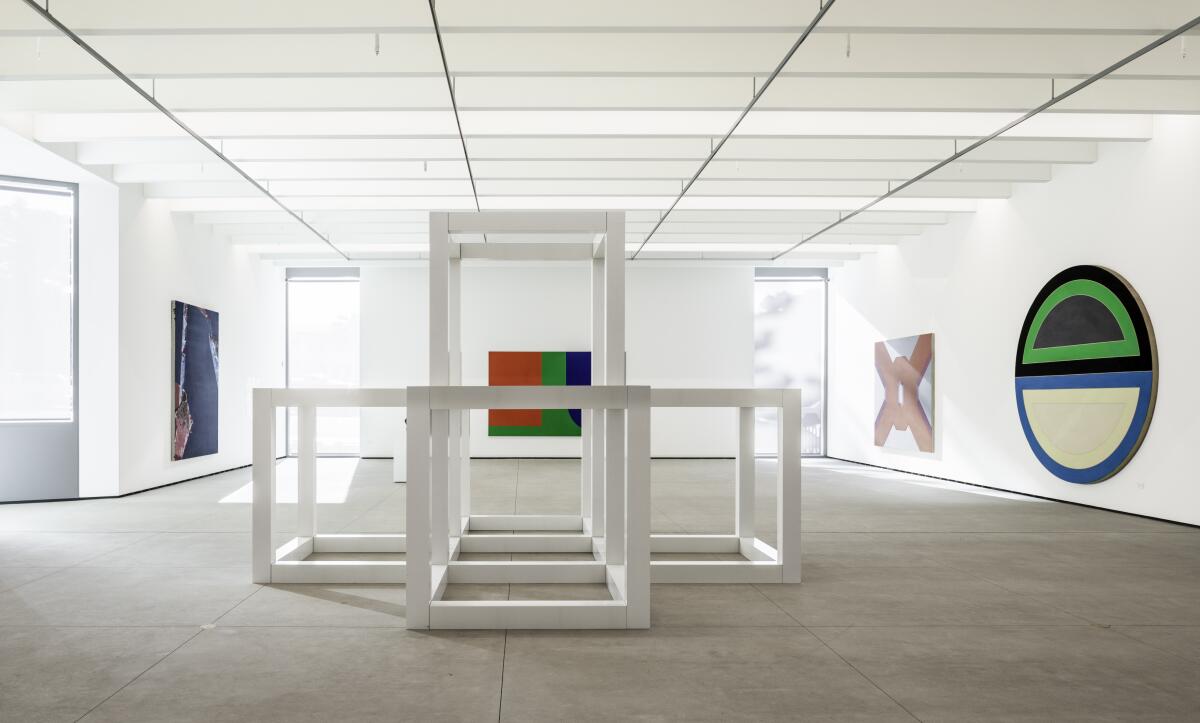

At Regen Projects, Mexican artist Abraham Cruzvillegas has created a show that looks nothing like what he has made before. Titled “Tres Sonetos,” the exhibition features large abstract paintings, small photo-based works and bright geometric sculptures. Inspired by the structure of a poem by Concha Urquiza from which the show takes its name, Cruzvillegas’ pieces grapple with the instability of identity. “It’s very important for me to face myself in a political way that is not literal or didactic or even narrative,” Cruzvillegas tells Times contributor Christina Catherine Martinez. “To construct something that can produce questions.”

Classical notes

The Los Angeles Philharmonic’s 12-hour new-music bonanza made a comeback after a pandemic-induced deep freeze. With so many performances going on, at times simultaneously, classical music critic Mark Swed says that he, like so many other attendees, made his own festival. His standouts included Annie Gosfield’s “The Secret Life of Planets: Heavenly Bodies and Earthly Gossip,” a 37-minute song cycle that returns to the score from her opera, “War of the Worlds,” as well as Chris Kallmyer’s “Song Cycle, Live by Special Request,” in which the composer called forth quotidian sounds such as birds, children, a violin and a chorus. “As he repeated them,” writes Swed, “they developed into increasingly specific and surprising instances.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Swed also reviews a pair of recent shows by pianists Lang Lang and Yuja Wang at Disney Hall. “Both are highly image-conscious,” he writes. “Both have seemingly superhuman techniques. Both enjoy (and encourage) pop-star-style fan bases. Both have tried, with varying success, to overcome the sniffy charges of flashiness. The fact is, they are flashy. But they happen to be exceptional musicians who take themselves very seriously.”

“¡Viva Maestro!” is a new documentary about L.A. Phil musical director Gustavo Dudamel, directed by noted documentarian Theodore Braun. The film captures Dudamel around the time of the 2017 constitutional crisis in his native Venezuela. “What we learn in the end about Dudamel is his exceptional ability to compartmentalize,” writes Swed of the doc. “While he stands in front of an orchestra, his entire being is focused like a laser on the music. But that focus requires an extraordinary responsibility, and the conflicted responsibilities toward the well-being of El Sistema children and the political realities of Venezuela are here seen as the greatest test of Dudamel’s life.”

On an unrelated note: The other day, I caught a short but very intriguing piece of a radio interview about the opera “Omar,” written by Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels and based on the life of Omar ibn Said, a Muslim Senegalese man who found himself enslaved in South Carolina and wrote a memoir in Arabic about it. The opera will be landing in Los Angeles courtesy of L.A. Opera later this year, which inspired me to do a little bit of reading on Said’s life. The Post and Courier in South Carolina has done some extensive reporting on his origins, and it is definitely worth a read.

On and off the stage

Pearl Cleage’s “Blues for an Alabama Sky” recently opened at the Mark Taper Forum, directed by Phylicia Rashad. The play tells the story of Angel (played by Nija Okoro), a nightclub singer going through a rough patch, and the makeshift family-of-friends that surrounds her: Guy (Greg Alverez Reid), a costume designer, and Delia (Kim Steele), a social worker. The play, writes theater critic Charles McNulty, “moves with the languor of a Tennessee Williams drama. The pace can feel sluggish at points, but the relationships of the characters sustain our interest even when their individual storylines seem stalled or muddled. Fate, ultimately, is of less emotional consequence than friendship.”

Design time

I spent some quality time in San Diego recently and paid a visit to two museum renovation and expansion projects that are definitely worth checking out. The first is the $105-million project that has remade the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego in La Jolla, by Selldorf Architects, which added gallery space, smoothed out confused circulation patterns and reoriented the entire complex to face the sea. The second is LUCE et studio’s $55-million renovation of the Mingei International Museum at Balboa Park, which has refreshed the ground floor, added a flexible indoor-outdoor amphitheater and opened up the second-story terraces to the public.

The projects are very different but share a few qualities: difficult sites, the task of preserving historic structures while adding something new, and they both integrate the SoCal outdoors into buildings that are often tombs of HVAC. Plus, go figure, both projects were led by women architects.

Essential happenings

Dance theater from Spain that blends flamenco and traditional ballet. A touring production of “Rent.” And a performance by Complexions Contemporary Ballet at the Wallis. Matt Cooper has the six best L.A. picks for the weekend.

On Thursday evening, I caught a performance of “In Our Daughter’s Eyes” at REDCAT, a new one-man opera by composer Du Yun (who previously worked with the Industry on the groundbreaking “Sweet Land”), in collaboration with librettist Michael Joseph McQuilken. The opera features baritone Nathan Gunn playing a man who is grappling with impending fatherhood, his worst tendencies and a whole host of things that are about to go fatally wrong.

If the beginning scenes leave Gunn’s character a bit poorly defined, everything shifts once inevitable tragedy begins to rear its head — and I found my eyes and my ears glued to the stage. Were those heavy metal guitar licks being used in an opera to convey grief? I believe they were.

In addition, the set design is smartly executed, making much of an architectonic shell.

“In Our Daughter’s Eyes” is playing through Sunday at REDCAT.

Moves

Veronica Roberts has been named the new director of the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University.

Passages

Gail Needleman, a Bay Area scholar who helped get vintage folk music on tape, is dead at 73.

In other news

— In advance of the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, our Books team has put together a comprehensive package on everything literary in L.A. — including a guide to L.A.’s best bookstores (to which yours truly contributed a few entries).

— A new short film by Waldemar Januszczak looks at the attempts to preserve cultural heritage in Ukraine.

— And Alex Marshall of the New York Times reports on how Russian ballet — a point of cultural pride in that nation — has been upended by the war.

— The uprisings of 2020 saw countless colonial monuments around the world come down. But in Santo Domingo, a prominent statue to Christopher Columbus remains. “To displace the bronze statue,” writes Jennifer Baez in Hyperallergic, “would be to destabilize the very idea of nation and surrender the coveted allure of primacy in the Americas.”

— Architect Bjarke Ingels’ firm BIG has designed a building in the metaverse. And I’m not saying that it looks like a Zaha Hadid, but I’m also not saying it doesn’t look like a Zaha Hadid.

— The story of the Peter Bogdanovich / Barbra Streisand flick that messed up a plaza staircase in San Francisco, and remains messed up to this day.

— What is it with the Spanish and their crazy updates of vintage art and architecture?

And last but not least ...

When real life is like the movies. Or why humanity is doomed.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.