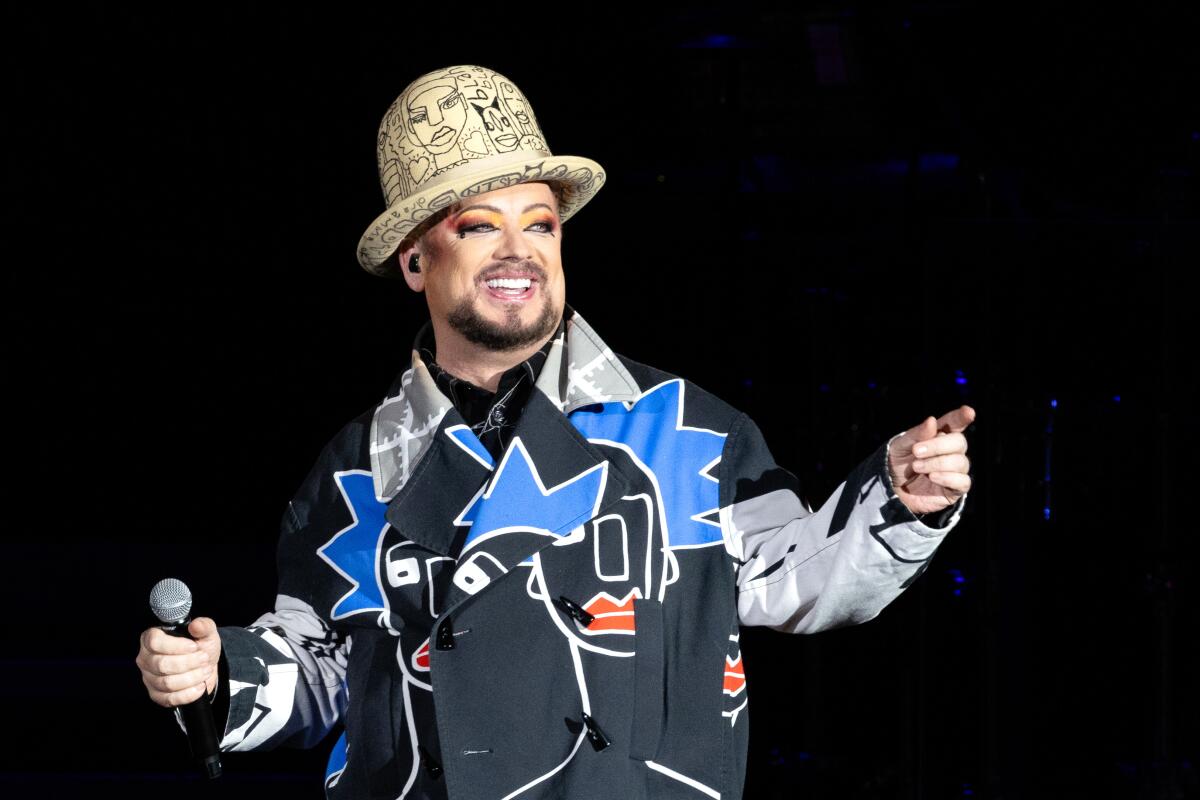

Culture Club’s Boy George: ‘I’m not anti-anyone. I’m not even anti-normal people’

Forty-one years after they hit No. 1 in their native U.K. with “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me,” Boy George and Culture Club will stop at the Hollywood Bowl this weekend for shows on Friday and Saturday nights.

In some ways, of course, the flamboyant pop-soul group — on the road with George, founding guitarist Roy Hay and bassist Mikey Craig, but minus original drummer Jon Moss, who left in 2018 — remains an indelible icon of the early-1980s New Romantic scene that also produced fellow MTV faves such as Duran Duran and A Flock of Seagulls; in other ways, Culture Club’s eclectic sound and racially diverse lineup — not to mention Boy George’s fluid performance of gender — makes it seem now like a harbinger of so much music and art that was to come.

Which isn’t to say everyone got the band’s vision. “The L.A. Times used to write the most stinking reviews of Culture Club back in the day,” Boy George, 62, said with a laugh during a recent phone call from a tour stop in Arkansas. “I remember there was one guy who really just didn’t like us.”

What was the gist of the reviews?

One of the things I’ve always hated in my career is when I read something and the writer’s pretending to understand what I’m thinking or what my motivation is. There was a lot of that in the ’80s — being told what your agenda was when it wasn’t. We had no agenda other than showing up, being creative, entertaining people.

I assume you know Neil Tennant of Pet Shop Boys, who famously started out as a pop critic.

He reviewed us. Culture Club played a gig at this club Heaven, and Neil wrote that I sounded like I’d gone to the Bryan Ferry/David Sylvian School of Vocals. I do have a vibrato, and I love Bryan Ferry and [Sylvian’s band] Japan. But there’s no way you could compare my voice to theirs.

Anyway, in those days we didn’t realize you can’t just kind of go up and attack journalists. We were young. So we saw Neil later — myself and Mikey, because he was the biggest, butchest one — and I said, “Let’s go talk to him.” He said what journalists always say: “Oh, I didn’t mean it, I was on my period.” In person they never just say they hated you. Whatever. It’s funny because obviously he went on to become a fantastic pop star.

You’re playing a show in Arkansas after we talk. Have you spent much time in the American south over the course of your career?

In the early days we never came down here, but there was a turning point in the ’90s where we started to come down to Texas and Dallas and all those places. I don’t feel any kind of weirdness here, but I’m well aware that I could easily upset the crowd by saying the wrong thing. I have that playful energy in me. Sometimes I do say it, but on this particular tour I’m avoiding it.

Why?

I find other things to say that are funnier. Also, I think I’ve developed this very strong radar for the mood of where I am. A lot of my gay friends, particularly the eccentric ones, will say the same thing, because when you’re walking down the street looking weird, you never know who might start in on you. And there’s a mood in the world at the moment. The new enemy is trans people, and because of the internet, people are getting tidbits and just spouting them out as if they’re the truth. It’s dangerous. And as much as I kind of play around, I don’t like being bullied by either side. I joke that I’m a fairy on both the right wing and the left wing. Obviously, I’m a lefty. But I was never asleep — I didn’t need to be woke up.

Before year’s end, rising country star and unlikely celebrity-gossip focus Morgan Wade will release a new album, run an ultramarathon and undergo major surgery.

Are you troubled by the anti-trans legislation that’s been passing in various states in the U.S.?

It’s disturbing, of course. I’ve known trans people for many, many years, and all the ones I know are just trying to get from A to B without getting attacked. I’ve been accused of being misogynistic because I won’t be anti-trans — this whole argument about trans people eliminating women. But I’m not anti-anyone. I’m not even anti-normal people.

We tend to remember the New Romantic scene as an oasis of inclusivity. Was it as open-minded as the legend suggests?

I don’t think it was, necessarily, but it was also a very small corner of the universe. The New Romantic scene that I came from — the sort of post-punk New Romantic thing — was one tiny club. And then little clubs popped up around the country and around the world. I was shocking in the pop realm because I was one of the first people who turned up and said, “This isn’t fancy dress — this is who I am.”

I’m older now. I don’t define myself by what I wear. But at that point everything was about how you looked, how you walked into a room. You treasured your individuality and you liked the fact that people were a little bit uncomfortable. I say onstage every night, “Remember when I was the only weirdo? Now they’re everywhere.”

Do you take pride in that?

I can’t sit here now and say I had a mission. The makeup thing for me started because I’ve got a very plain face — nice eyes, but a plain face — and once I started playing around with makeup I realized I could look like a totally different person. Suddenly I was very pretty, and the boys bought me drinks.

You remember the first time you wore makeup in public?

I remember going to a club with black lipstick and a little coal around my eyes — a place called Madam Louise’s [in London], which was a sort of after-hour speakeasy that was frequented by the Sex Pistols and Siouxsie and the Banshees and all those people.

Did it feel liberating in some way?

Not when you were around other people [like that]. It was when you got on the bus or the train to go home. Do you wipe it off?

Did you?

I don’t think I did. A lot of my friends back then would come out at night dressed up and then they’d have normal jobs. When they saw me coming down the street in the middle of the afternoon like Carmen Miranda, they used to dive into shops to avoid me. At least until I got famous. Then it was, “George! Let’s get a coffee!”

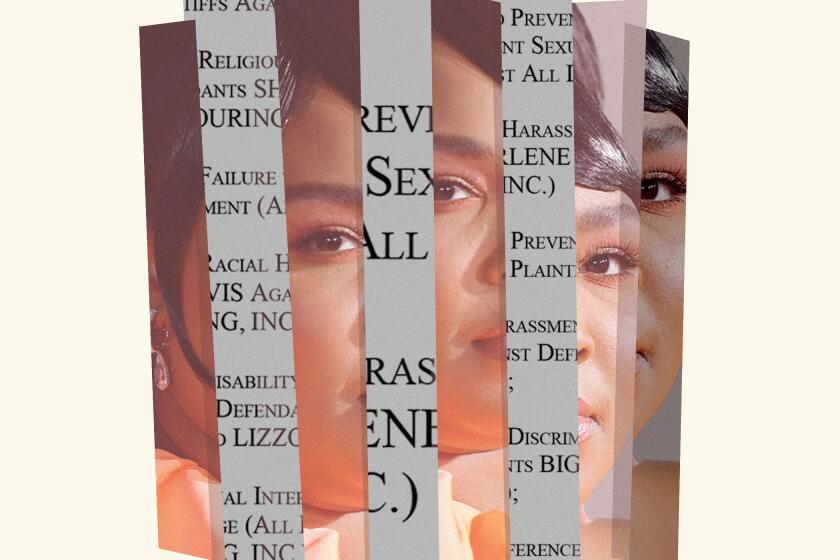

Lizzo is facing a lawsuit from former backup dancers that threatens to undo her hard-won image as a beacon of empowerment and self-acceptance.

I wonder whether having worn makeup from Day 1 has made aging as a public figure easier for you.

I look at some of my contemporaries and I think, Why have you never slapped on some foundation? Newsreaders wear it. Donald Trump wears it. [David] Bowie always wore it when he was older.

Name a famous person slightly older than you who’s aging in a way you admire.

Glenn Close is looking good. She still looks like Glenn Close. I joke all the time that I’m gonna be the only person left with their own face. Every single time I go out, someone comes up to me and says, “Your skin’s amazing. What do you use?” I say, “Nothing.” They say, “You’re lying. You’ve obviously had Botox.” But I have never, ever had it.

Might you someday?

Never. It’s taken me years to get to a place where I can look in the mirror as George O’Dowd and say, “You’re quite a handsome man.” But I’m not making judgments about what other people want to do. I’ve got a few straight friends who are obsessed with Madonna right now because she’s a little fuller, a little more matronly.

This year you and the rest of the band settled a lawsuit with Jon Moss, who says you expelled him from Culture Club and defrauded him out of tour earnings. The two of you were once romantically involved. Think you’ll ever speak to him again?

The important thing is that I don’t hate Jon. I never hated Jon. Jon was the one who went legal. We didn’t go legal. I suppose in a way I was waiting for him to turn up and maybe have a cry and say, “I want to be in the band and I want to listen to everyone else and I want to be part of this and it means something to me.” But instead he took legal action because he couldn’t control the band anymore. He knows me well enough to know that he could have come to me and I would have put him back in the band.

I mean, even now, there’s always hope. But the thing is, when we were putting this tour together, Jon said to us, “Can I come back for the Hollywood Bowl?” I said, “You want to come back for the big gigs, but you don’t want to go to Arkansas or Charlotte, North Carolina?” And it was basically, “Yeah.” I said, “Well, that won’t work.”

What’s the best song you ever wrote?

For me right now it’s two new songs: “Swoon” and “Not Quite Havana,” both Latino kind of tracks. If they’d been out in the ’80s, they would have been on fire.

Of the old songs, I’d say the last track on Side 1 of “Colour By Numbers,” “That’s the Way (I’m Only Trying to Help You),” which I used to do with [singer] Helen Terry. It’s a piano thing, and it’s about my mum — about the way she was sort of suppressed by my dad’s jealousy. My mum was this very creative, talented woman who could make a wedding dress, make you curtains or chair covers. She was very gifted and had a lot of personality, and my dad just couldn’t deal with it.

Did witnessing that shape your ideas about masculinity in any way?

I’m a gay man, so I’m turned on by masculinity — even aggressive masculinity. I like uptightness because it’s part of my experience. Most gay people grow up trapped in this sexual world because no one else is talking about what you are, except for saying it’s wrong. And then you see your parents, who are supposed to represent what’s normal and right, fighting and treating each other badly. So you walk into the world with a very edgy understanding of love. But you definitely become a good lyricist because of that.

What’s the worst song you ever wrote?

Originally we were a bit embarrassed by “The War Song” [from 1984], but it’s kind of turned the corner in the last 10 years. There’s a truth to it — war is stupid. We’ve talked about putting it back in the set. Maybe we’ll do it at the Bowl.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.