Back in March of 2020, the popular Australian dance-music trio Rüfüs Du Sol moved into a Joshua Tree compound for two weeks to write their new album “Surrender.” As COVID-19 descended on L.A., they stayed in the desert for months, with no idea when they’d ever play a show or see home again.

“Every morning before writing, we tried to do a meditation, talk about our feelings and leave everything else outside,” said singer Tyrone Lindqvist.

“We spent a lot more time out there than we intended,” added keyboardist Jon George, “because we were so scared to come back.”

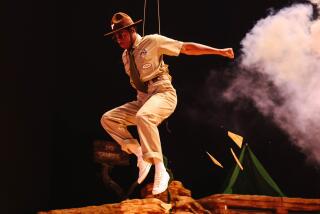

In November of 2021, the band returned to L.A. with three sold-out nights at the Banc of California Stadium. Around 70,000 fans packed the open-air arena for the trio’s first SoCal shows since the pandemic began.

“Walking out onstage, there was a healthy amount of nerves,” said drummer James Hunt. “I remember how intense that energy was. You could feel that people hadn’t seen music in a year and a half.”

Live music in 2020 was a riptide of fear and confusion, dragging the whole business out to sea. 2021 was a desperately needed life raft, but at year’s end, it’s still an unsteady one.

“When things got better and vaccines started to reach 60% of the population, I heard things like ‘Whoa, this will be the greatest renaissance in the history of entertainment,’” said Randy Phillips, the former CEO of AEG Live who produced Kanye West’s feud-breaking concert with Drake last week at the L.A. Coliseum. “But there’s hidden danger in those numbers too. Sales for a bunch of arena shows were soft, and that’s a function of the fact that people aren’t rushing indoors yet. Layer in Omicron, and I’m still cautious.”

Thanks to deep-pocketed streamers with an insatiable need for content and subscribers, music fans enjoyed an unparalleled bounty of documentaries in 2021.

The live industry had gone completely dark for a year and a half: Beloved venues closed, crews lost livelihoods and artists feared for their careers. In L.A., concerts were semiofficially resurrected in May, when the Los Angeles Philharmonic performed a comeback show for essential workers at the Hollywood Bowl.

Next came outdoor festivals, indoor dance clubs and long-delayed arena dates. For a few weeks in summer, from the Greek Theatre to downtown after-hours clubs, live music was a long-overdue joy.

2021 was supposed to be an exhilarating comeback, and in many ways, it was. At year’s end, live music is definitively back in L.A. — but not without notes of worry.

The Delta wave kneecapped any sense that COVID-19 was behind us. Venues scrambled to adapt to fast-changing rules and best practices around vaccine mandates, mask policies and slipping public resolve.

“The live music industry has clearly suffered throughout COVID-19,” said Scott Clayton, co-head of global music for United Talent Agency. “We finally saw daylight with the vaccination rollout, but the road back to live has still been a rough ride. One positive test can derail an entire tour.”

“The live business overall is very healthy,” Clayton continued. “There is no substitute for the communal experience of live shows, and there is a huge demand from fans to see their favorite artists perform. That said, there is still concern around variants and the number of people who remain unvaccinated.”

But after summer’s euphoria, the concert industry was struck fresh with tragedy in November. The crowd-crush disaster at the Astroworld Festival devastated the city of Houston and the career of the fest’s Travis Scott.

And now the Omicron variant, which appears more infectious than even Delta, could dampen the live music business yet again.

“The live business is as healthy as it has ever been, when the shows are able to come off in a safe way,” said Ray Waddell, president at Oak View Group, parent company to the live-business trade publication Pollstar. “This year, we saw that people are willing to put up with a lot of inconveniences just to be able to see shows. How long that will last, we’ve yet to see.”

On paper, at least, the return to stages is already in full bloom. Pollstar’s year-end estimates track a global concert industry that rebounded from a dismal $18.9 million in first-quarter gross revenue to $1.34 billion in the final quarter of the year. Tours from the Rolling Stones, a reunited Los Bukis, Harry Styles and the Hella Mega package tour of Green Day, Fall Out Boy and Weezer drove huge turnout from the summer into winter.

Based on the end-of-2021 stats, Pollstar expects the top 100 tours of 2022 to sell around 65 million tickets, which would put them 12% above even the windfall year of 2019. Adele’s upcoming Las Vegas residency is likely to break records.

“After the tremendous losses of 2020, the industry has no taste for another shutdown. There would be extreme resistance to that,” Waddell said. “There is so much work planned that there are very real shortages of gear, labor, transportation and available dates.”

Even beyond the economics, “I feel like there is newfound respect for the value of the live thing, from fans to artists and those who work in the business,” Waddell added.

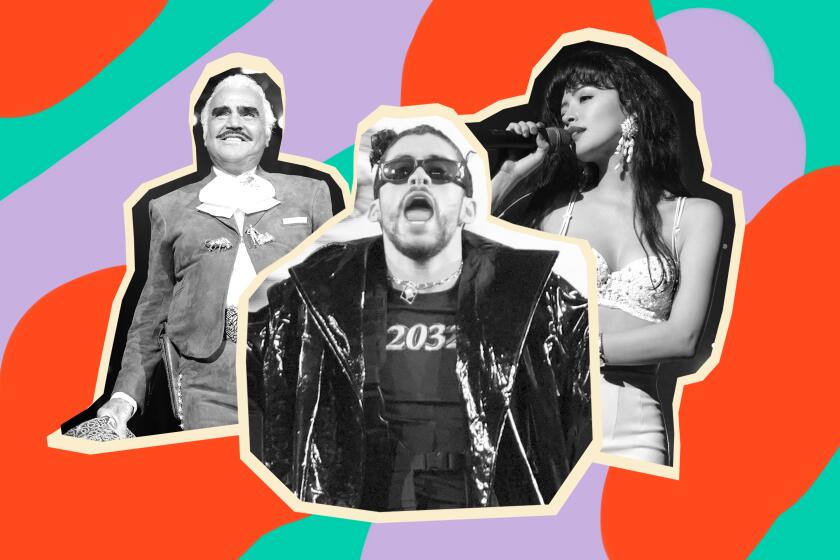

In 2021, Latin music made room for energizing new sounds and faces, while bidding farewell to one of its true icons.

Companies made new bets on live music in 2020, like the opening of YouTube Theater at SoFi Stadium in Inglewood. Closed spaces like the Hi Hat and Bootleg Theater were revived as the Goldfish and 2220 Arts + Archives, respectively.

But fans and artists remain justifiably nervous. Stevie Nicks canceled her 2021 dates out of pandemic-surge fears. Live Nation’s stock, having rebounded from 2020 lows, wiped out most of its fall 2021 gains in just the last month. NBA game cancellations, in a grim echo of 2020’s pandemonium, are again spooking indoor crowds. Some concerts — especially by boomer-friendly acts — experienced no-shows from cautious ticketholders, as much as 20% in some cases.

Outdoor festivals are a bright spot, but Phillips worried that “people are just not rushing back into theaters. That portends to where we are with arena and smaller venue shows. I’m not seeing the strength and resiliency of box office for many headline artists.

“I get why festivals are flourishing, because there’s space outdoors,” he continued. “But you’re starting to see new restrictions in the U.K. Even if isn’t lockdowns again, the fear of it slows growth, and it will take a little time before consumer confidence is restored.”

While the Delta wave initially gave pause to fans and promoters who had hoped for “Summer of Love”-style delirium, outdoor festivals like Lollapalooza and HARD Summer proved to be relatively safe environments for fans to cut loose. It was a build-the-plane-as-you-fly-it kind of scramble for acts to secure tour dates, though.

“We had to rebook dates three or four times,” Rüfüs Du Sol’s Lindqvist said. “It was really challenging to lock in outdoor venues with double the bands going out.” The band required vaccines and masking for its crew. “I can’t imagine the juggling it took for our tour and production managers,” he said.

“The logistical challenges of touring during this pandemic have been massive,” UTA’s Clayton agreed. “We were all figuring out the safety protocols for the first time. It was very difficult for promoters to hire enough stagehands and venue staff, and those issues became magnified for tours that were requiring vaccinations.”

After two years, when even industry giants like Coachella bowed to COVID’s evolving week-to-week threats (it’s now scheduled for an April 2022 return), new events like Goldenvoice’s This Ain’t No Picnic and the inaugural L.A. edition of Barcelona’s Primavera Sound are locked in for next year.

“Relief, that would be the word,” said Alfonso Lanza, the co-director of Primavera Sound, which will make its long-postponed L.A. debut in September at L.A. State Historic Park in Chinatown, with headline sets from Lorde, Nine Inch Nails and Arctic Monkeys. “We tried in 2019, then 2020, then 2021, and it finally looks like 2022 is our year.”

For local acts who waited out the pandemic as beloved L.A. independent venues closed or lost staff, many in the scene desperately sought work elsewhere or reimagined their artistic futures.

When Thea Martre, the singer and guitarist for the local indie-rock act Fox Violet, took the stage for the first time in a year-and-a-half in December at the Troubadour, she was “pretty emotional, but in a lovely way. It was a full-circle moment,” she said. “A lot of sad things happened; we lost a bunch of venues like the Satellite, which was a huge hub for the local scene.”

But into the next year, she added, “I can see massive resurgence too. We know how fragile it is.”

That fragility was made clear this year for nonpandemic reasons as well.

The Astroworld disaster, where 10 fans died in a crowd surge and hundreds more were injured during headliner and festival founder Travis Scott’s set, joins 2017’s Route 91 Harvest shooting in Las Vegas, 2016’s Ghost Ship warehouse fire in Oakland, 2003’s Station nightclub fire in Rhode Island and the Who’s 1979 Cincinnati show as the worst concert disasters in the U.S.

Scott was slated to headline Coachella next year, alongside Rage Against the Machine, but outlets now report he will almost certainly bow out. Lawsuits stemming from the incident seek damages into the billions from promoter Live Nation, security and medical firms, streamer Apple Music and guest star Drake.

“In the wake of Astroworld, we’ll see more emphasis on crowd control and logistics around front-of-house and general admission,” Waddell said. “The industry always responds to tragedy with more safety measures. Nobody wants to see this type of thing happen.”

But Phillips expects insurance and security costs to rise for big events, after two years of heavy income losses. “Even before Astroworld, you couldn’t get COVID-19 liability coverage. You can’t throw more obstacles at an industry than COVID-19 and Astroworld. It’s a perfect storm.”

The new year of live music will likely be neither fully liberated from the pandemic nor as dreadful and unsure as the last two years have been. Omicron is all but guaranteed to bring a new wave to the U.S.; vaccine boosters and new medicines could keep it navigable for the live industry though. Few in the industry or government seem eager to reinstate shutdowns around live events.

No one in live music has any illusions about the possibility that things can go haywire. But even the most grizzled promoters leave 2021 with some cause for optimism for next year.

“We’ll need to adapt to any measures, but the feeling is almost normality. Big fests have happened in the states. Maybe by the time of our fest in September, it’ll be fully normal,” Primavera Sound’s Lanza said. “We’re humans — we went two years without live experiences, and nothing substitutes for that.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.