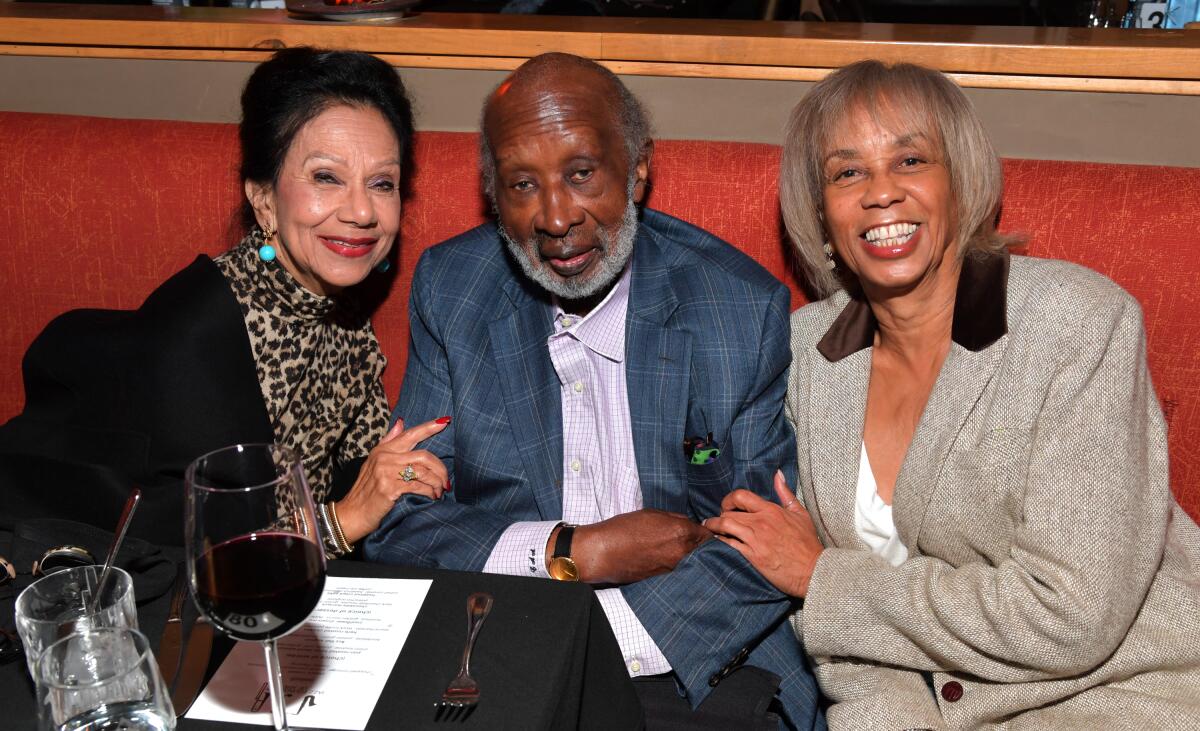

What to know about Clarence Avant, husband of the late Jacqueline Avant

Clarence Avant is a legend in the entertainment industry, known by many as the “Black Godfather,” a revered but limelight-shunning nonagenarian. And he was married for 54 years to Jacqueline “Jacquie” Avant, who was fatally shot early Wednesday by suspects at their Beverly Hills home.

As lionized as he is, including in a 2019 documentary, Clarence Avant is not a household name to many outside the worlds of music, sports, film and politics.

For the record:

1:53 p.m. Dec. 2, 2021A previous version of this story spelled the diminutive of Jacqueline Avant’s first name as Jackie rather than Jacquie.

The 90-year-old music executive, who was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame this year, grew up as a poor kid in Depression-era North Carolina. He rose to become a behind-the-scenes titan of managing, deal-making and problem-solving across the spectrum of Black entertainment.

“Clarence is a guy who wasn’t looking for the job he ended up with,” entertainment magnate David Geffen said in “The Black Godfather,” Netflix’s recent documentary about Avant that was directed by Reginald Hudlin.

Jacqueline Avant, L.A. philanthropist and wife of music producer Clarence Avant, is fatally shot during an apparent home invasion robbery.

After joining the music business in New York in the 1950s, he was mentored by the late, mob-connected Joe Glaser, the legendary manager of Louis Armstrong. Avant started out managing a previous era’s jazz and soul royalty, including jazz singer Sarah Vaughan, jazz musician Jimmy Smith and Argentine composer-pianist Lalo Schifrin. Schifrin was the reason Avant relocated to Los Angeles in the late 1960s.

Avant met his future wife, then Jacquie Gray, who had modeled as part of the traveling Ebony Fashion Fair aimed at introducing new styles to Black communities, in the mid-1960s. By then a player in the New York music business, he wooed her with VIP treatment at such clubs as Birdland and the Apollo Theater.

As the years passed, he became involved in the beginnings of today’s R&B and rap empires, with sports and politics thrown in for good measure. Some name-dropping achievements include working in a promotional role on Michael Jackson’s 1987 Bad world tour and mentoring the songwriting-production team of Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds and LA Reid.

If your currency as a documentary subject lay in the number of heavyweights taking time to sing your praises on camera with twinkles in each one’s eyes, then music industry executive Clarence Avant may be, like George Bailey in “It’s a Wonderful Life,” the richest man in town.

Avant reached out to Hank Aaron to coordinate a Coca-Cola endorsement before the late baseball legend broke Babe Ruth’s home-run record in 1974. He produced a prime-time special that helped Muhammad Ali transition from retiring boxing star to beloved entertainment figure, insisting that the network hire a Black director for it.

He helped pave the way to bring national politicians together with the entertainment industry’s Black community, putting together a star-studded concert for Andrew Young when the civil-rights icon — later named U.S. ambassador to the United Nations by President Carter — was running for Congress in 1972.

Avant launched Sussex Records, the second of his two labels, in late 1969 and launched the career of singer Bill Withers. The singles “Ain’t No Sunshine,” “Lean on Me” and “Use Me” all came out on Sussex, which shut down in 1975.

He created Avant Garde Broadcasting in 1971, and the company — which would go bankrupt in 1975 — bought the license of an Inglewood radio station that was one of the country’s first Black-owned broadcasters.

“Bill Withers summed up his impact by declaring, ‘He puts people together,’” the Rock Hall says on its website.

Avant fought for Black artists throughout the 1970s and 1980s, eventually becoming chairman of the Motown board of directors. He executive produced the Paramount Pictures film “Save the Children,” a documentary about a 1972 concert in Chicago that featured the likes of Sammy Davis Jr., Marvin Gaye and the Jackson family. The concert was interspersed with footage of children, most of them Black, in terrible conditions around the world.

Nicole Avant is a Democratic dynamo, just like her dad. But they split on candidates.

The Avants raised a son, Alexander, and a daughter, Nicole. Alex is an entertainment executive. Nicole, a film producer, was brought up in the family businesses — music and politics.

She is married to Ted Sarandos, co-chief executive and chief content officer at Netflix. Nicole was a fund raiser for Barack Obama when he ran for president in 2008, opposing her father, who backed Hillary Clinton.

“His attitude was, ‘You’re a grown woman. You can make your own decision,’” Nicole Avant told The Times in 2007. She wound up being named President Obama’s U.S. ambassador to the Bahamas from 2009 to 2011.

Music icons Clarence Avant and Quincy Jones paved the way years ago, bringing national politicians together with the entertainment industry’s African American community.

Clarence Avant was honored with a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame in 2016.

In October, at the Rock Hall’s induction ceremony, he was given the Ahmet Ertegun Award, a commendation for executives in the industry. It’s named after the late Atlantic Records co-founder who started the Rock Hall with Rolling Stone’s Jann Wenner in the mid-1980s.

“Beautiful moment last night at the @rockhall for my Dad,” Alex Avant posted on Instagram on Halloween, including video of memorabilia chronicling his father’s career. “So so so happy for you. Yes, long overdue but it’s now official.. Love ya!”

The shooting death of Jacqueline Avant at home brought grief, shock and remembrances from the worlds of politics, entertainment and L.A. philanthropy.

On Wednesday, after the slaying of his 81-year-old wife by suspects who entered their Trousdale Estates home, the elder Avant was said to be “safe” and “currently grieving but resting with his family,” according to a Los Angeles Sentinel statement.

Times staff writer Randall Roberts and freelance writer Robert Abele contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.