Bruce Springsteen is Democratic Party royalty. Is he also a symbol of its decline?

One day in 1968, Bruce Springsteen received a draft notice from the Army, summoning him to join the Vietnam War. Springsteen was 19 and had dropped out of community college to focus on the two things he loved most: singing and playing the guitar. He didn’t want to join the Army, not only because it was far from the rock clubs of the Jersey Shore but also because he didn’t believe in the war.

The previous year, civil rights protests in Newark, N.J., had spread 40 miles south to Freehold, Springsteen’s hometown. There was “rioting in Freehold,” Springsteen recalls in “Renegades: Born in the USA,” a new coffee table book that features a long conversation he and former President Obama had in summer 2020 about political awareness. (The two share a podcast with the same name.) Springsteen saw how Black men were overrepresented in the Army and had fewer economic opportunities than white people, and he developed “a feeling that the system was fixed and prejudiced towards a lot of its citizens,” he tells Obama.

In the book, Springsteen, 72, also explains the background of his political awakening. He describes Freehold as “your typical small, provincial, racist” American town, an insular, ur-American hamlet of Memorial Day parades and VFW marches. His parents didn’t talk about politics; they were more concerned with whether they could pay their bills. In grade school, when Springsteen asked his mother if the family were Democrat or Republican, she said: “We’re Democrats, ‘cause Democrats are for the working people.” For the most part, it was current events, not his parents, that began to form his politics.

More than just gossip about the toll of her divorce, the singer’s fourth album, ‘30,’ offers deep thoughts on love’s causes and consequences.

Springsteen successfully dodged the draft, he tells Obama, by pretending to be too stupid to fill out his draft papers. He’d recently been in a motorcycle accident that resulted in a concussion, and the Army declared him 4-F. The closest he came to Vietnam was writing “Born in the U.S.A.,” an elegy for a soldier who died in the 1968 Battle of Khe Sanh.

“Renegades” doesn’t continue to describe the progress of Springsteen’s emergence as a publicly political person. But you can see another stage of that progress in “The Legendary 1979 No Nukes Concerts,” a film of Springsteen and the E Street Band playing a flawless, herculean 90-minute set at Madison Square Garden as part of an antinuclear-power benefit concert. (The DVD, as well as a CD, was released Nov. 16.) One of the notable things is that at no point does he mention nuclear power.

For years, Springsteen had “demonstrated considerable unease whenever asked to speak politically,” Eric Alterman writes in his 2001 book “It Ain’t No Sin to Be Glad You’re Alive: The Promise of Bruce Springsteen.” Although Springsteen had performed at a fundraiser for George McGovern, the Democratic nominee for president in 1972, he admired singers like Bob Dylan, James Brown and Curtis Mayfield, who were socially conscious but not expressly political. Though he never declared himself a left-winger, people on the left found liberal themes in his songs. Then again, people on the right heard conservative themes.

In 1982, Springsteen released “Nebraska,” a stark, joyless album about hard times during late capitalism, about “debts no honest man can pay” and the “meanness in this world.” Music critic Greil Marcus, in his review, called it “the most complete and probably the most convincing statement of resistance and refusal that Ronald Reagan’s USA has elicited from any artist or politician.”

Springsteen’s next album, “Born in the U.S.A.,” turned him into the world’s biggest rock star. For more than a decade, as part of its infamous Southern strategy, the Republican Party had been repositioning itself as the party that spoke for the working people, to use Springsteen’s mother’s term. No wonder his stories about small town life attracted the attention of Republicans. “I have not got a clue about Springsteen’s politics, if any,” conservative columnist George Will wrote, “but flags get waved at his concerts while he sings songs about hard times.” Will called Springsteen’s songs “a grand, cheerful affirmation” of American life.

A few days later, while then-President Reagan was campaigning for re-election in New Jersey, he spoke admiringly of “the message of hope in songs so many young Americans admire: New Jersey’s own Bruce Springsteen.”

Did the premonitions of doom in “Cover Me” or the fantasy of “a better life than this” in “Working on the Highway” constitute a cheerful affirmation? Did the dead pal in “Born in the U.S.A.” or the racial violence in “My Hometown” comprise a message of hope? Of course not. But Springsteen used the iconography of the American flag often in the ‘80s, and as he began to realize, iconography isn’t part of the message, it is the message. He’d made it possible for the right wing to co-opt his music.

On the Born in the U.S.A. tour, he raised money for and contributed to local charities, mostly food banks. He felt, he later said, that he could build more credibility by remaining nonpartisan while saving his vision of progressivism for his music. Springsteen denounced Reagan’s embrace of his music, but when asked if he preferred Democratic candidate Walter Mondale, he shrugged: “I don’t feel a real connection to electoral politics right now,” he told an interviewer.

“There was always a political consistency in Springsteen’s songs,” says David Masciotra, author of the 2010 book “Working on a Dream: The Progressive Political Vision of Bruce Springsteen.” Masciotra cites several examples, including the antiwar song “Last to Die” and its companion, “Magic,” about political trickery, both from the 2007 album “Magic,” and “Streets of Philadelphia,” the theme song to “Philadelphia,” which in 1993 was the first Hollywood movie to address the AIDS plague. And in 2000, Springsteen began performing “American Skin (41 Shots),” which commemorates the death of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed Guinean immigrant who was shot 41 times by the NYPD in a case of mistaken identity. This was a song the GOP couldn’t co-opt — Mayor Rudolph Giuliani condemned it, and the president of the country’s largest police organization called the singer a “dirtbag.”

Springsteen’s politics, Masciotra adds, “are in the best of the American progressive tradition: an emphasis on the common ground of class interests and working people’s struggles set against exploitation of labor from the corporate class and the political system that enables it, plus a radical and redemptive form of empathy, whether it’s the immigrant, the Black American or the gay American experience.”

Springsteen wrote about politics without ever mentioning politics. Still, Masciotra says, “he wasn’t comfortable or at least confident expressing his politics in more explicit terminology.”

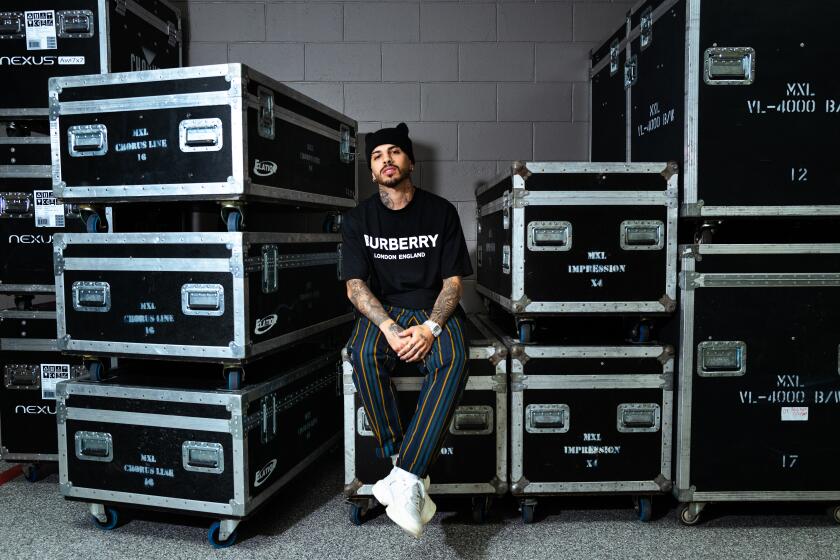

Rauw Alejandro is having himself a huge 2021: A worldwide smash with ‘Todo De Ti,’ three Latin Grammy nominations and a new romance with singer Rosalía.

Twenty years after “Born in the U.S.A.,” Springsteen gave up nonpartisanship to headline the 2004 Vote for Change tour, which featured musicians from Babyface to R.E.M., focused on registering young voters in swing states and advocated for Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry, who was running against incumbent George W. Bush.

“Why did you stay away from being actively involved in partisan politics for so long?,” Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner asked Springsteen in a 2004 interview.

“Sitting on the sidelines would be a betrayal of the ideas I’d written about for a long time. Not getting involved, just sort of maintaining my silence or being coy about it in some way, just wasn’t going to work this time out,” Springsteen replied. This election, he added, “is a time to be very specific about where I stand.”

The issues Springsteen cited in that interview are uniformly prescient: an emerging oligarchy in the U.S., economic inequality between rich and poor, the way politicians erase the line between truth and lies, the toxic influence of Fox News and the media’s devotion to appearing impartial are issues that have only grown in significance. They comprise much of the conversation in “Renegades,” even though Springsteen and Obama mostly avoid referring to Donald Trump, the personification of those issues.

After Vote for Change, Springsteen not only declared his support for Obama during the 2008 race but he also performed at campaign appearances and, later, at Obama’s inauguration. Since then, he’s become Democratic Party royalty. In 2016, he played at an election eve rally for Hilary Clinton in Philadelphia and also endorsed her, while calling her opponent Trump a “flagrant toxic narcissist.” And in the 2020 election, he narrated a TV ad for Joe Biden, allowed his music to be used by the candidate’s campaign and performed at Biden and Kamala Harris’ inauguration event.

Predictably, Springsteen’s advocacy has led to many charges from the right that he’s a “limousine liberal” who’s out of touch with America and who should shut up and sing. (Anyone who thinks his songs are distinct from his politics isn’t paying attention.) During the Vote for Change tour in 2004, Wall Street Journal editor Phil Kuntz wrote in an essay that his experience “as a diehard Bruce fan was about to become a little more difficult, a little less fun.” Increasingly, Springsteen’s conservative fans have struggled to reconcile their love of his music with their disgust at his politics. “I compartmentalize,” former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, a Springsteen fanatic, once said. “I find [Springsteen’s activism] particularly annoying, but I like his music,” Sean Hannity said earlier this year.

When Springsteen played a McGovern benefit, the Democrats were reliably supported by white working class voters, and the Republicans were the party of big business and the affluent. In the last 30 years, there’s been a significant inversion of class affiliation, culminating in Trump’s election; in 2016, white voters without college degrees favored Trump 64% to 28% over Clinton, and 65% voted for him in 2020, when they comprised 42% of the total electorate. The characters in Springsteen songs — the disillusioned Vietnam vet, the guy who makes his money racing in the streets — they’re likely Trump supporters now. If the Democrats lose the House in the midterm elections next year, it will largely be because the people who most resemble his characters no longer believe the same things he does.

Some people inherit their politics as a kind of birthright and join the same party as their parents. But there are families, like the Springsteens, for whom politics feel irrelevant. It’s one thing to embrace liberalism after growing up around liberals, and another to work your way toward it despite never having met a liberal as you were growing up. In “Renegades,” Springsteen outlines the slow but authentic path he took, starting in a small town where patriotism was synonymous with saluting the flag, and moving toward an understanding that patriotism isn’t about the flag, but about the ideals that flag represents.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.