In only 2021 concert, an ambitious Kendrick Lamar reestablishes his generational greatness

To answer the most pressing question: No, Kendrick Lamar did not use his first concert in two years to reveal that he’d completed his long-awaited new album, much less play anything from it.

But what a satisfying victory lap he ran instead.

Headlining the first night of this weekend’s second Day N Vegas festival — the inaugural 2019 edition of which served as Lamar’s last big show before the COVID-19 pandemic — the celebrated Compton-born rapper made clear that he knows he’s been missed: “Three hundred sixty-five days / Times two / Since I seen you,” he told the crowd at the top of his 1½-hour set, repeating the chant to escalating cheers from the crowd at the Las Vegas Festival Grounds. (Other acts at Day N Vegas, which runs through Sunday night, include Tyler, the Creator; Lil Baby; SZA; Doja Cat; and Post Malone, who stepped in for Travis Scott after Scott pulled out in the wake of last weekend’s Astroworld tragedy.)

Lamar understands too that fans’ patience is running thin for the follow-up to 2017’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “Damn,” which given a recent swell of activity — guest verses on tracks by Terrace Martin and Baby Keem, a booking for February’s Super Bowl halftime show, a much-discussed change in his Spotify avatar — feels tantalizingly close to dropping.

“Vegas, till next time,” Lamar said at the end of Friday’s concert. “And when I say ‘next time’ — very soon.”

Before he moves on, though, the 34-year-old took this opportunity — his only scheduled gig of 2021 — to look back over his groundbreaking work from the last decade, starting with his debut studio album, 2011’s “Section.80.” The concert was divided into four sections, with songs from each of his LPs in the order they were released; each section began with a few lines of text on a video screen behind Lamar describing his thoughts on the album: 2012’s “Good Kid, M.A.A.D City” was all about “real stories,” for instance, while “Damn” pondered his “relationship with fame and fortune.”

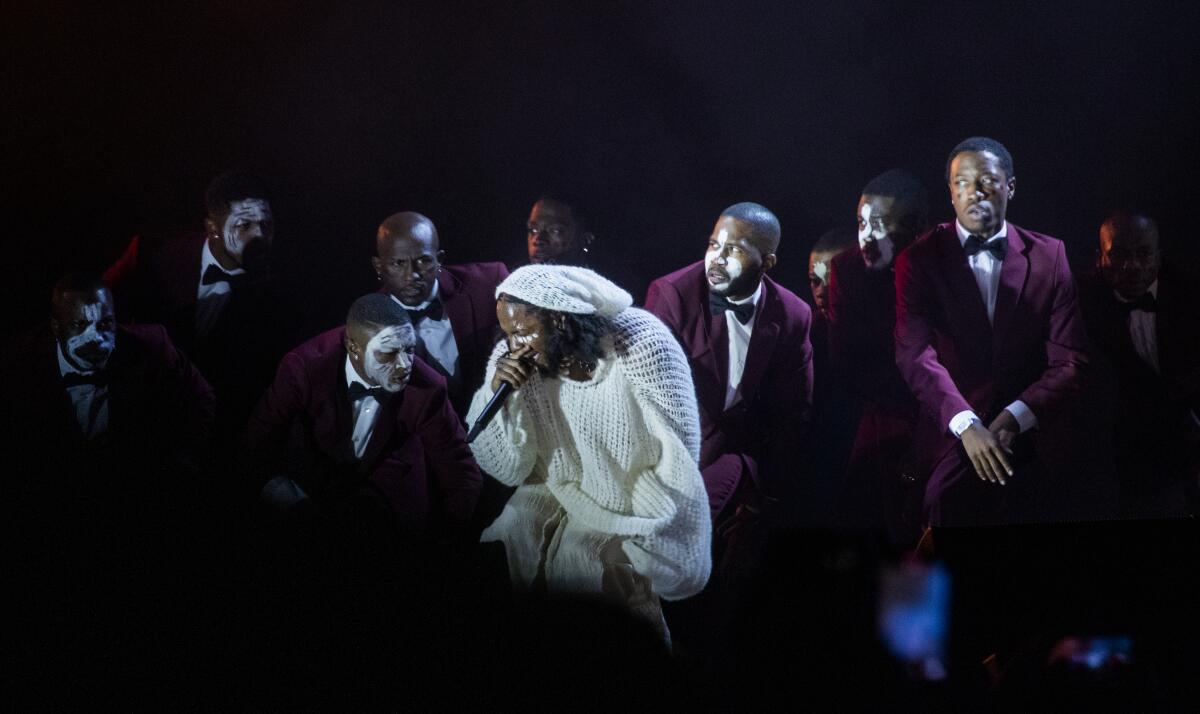

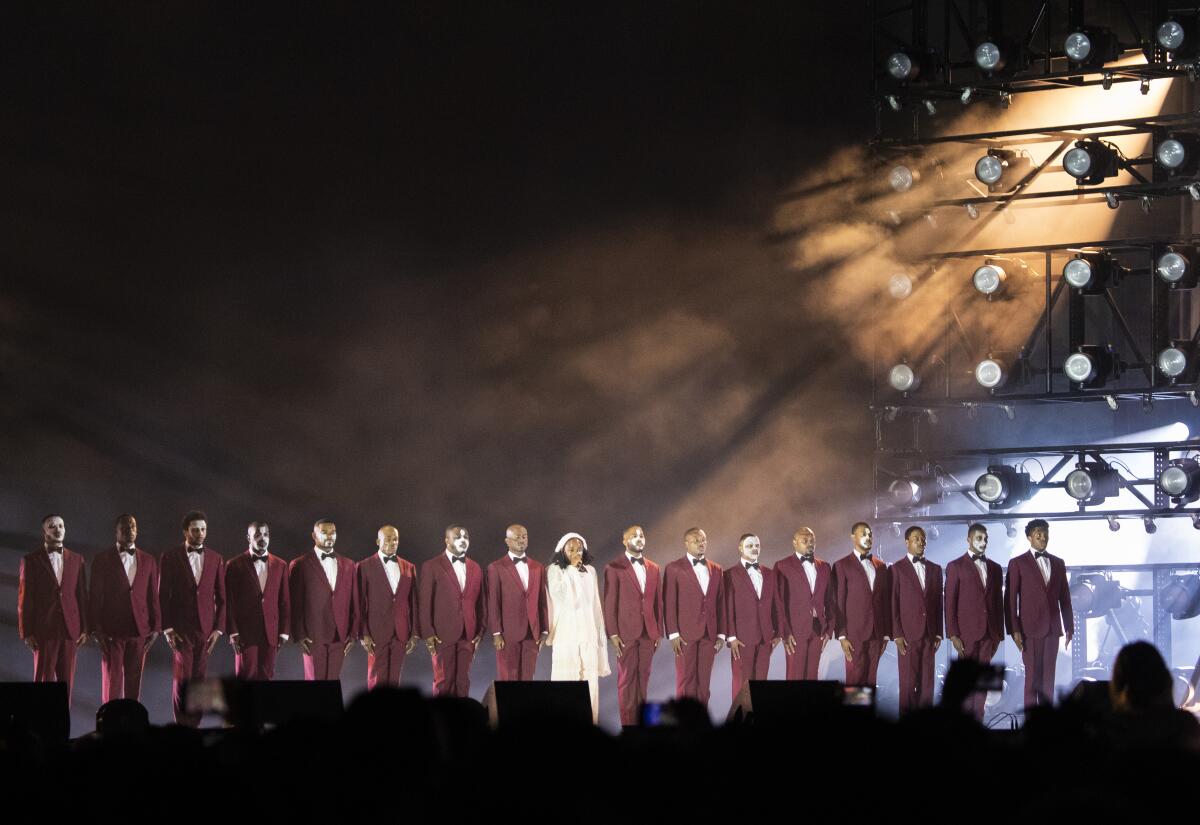

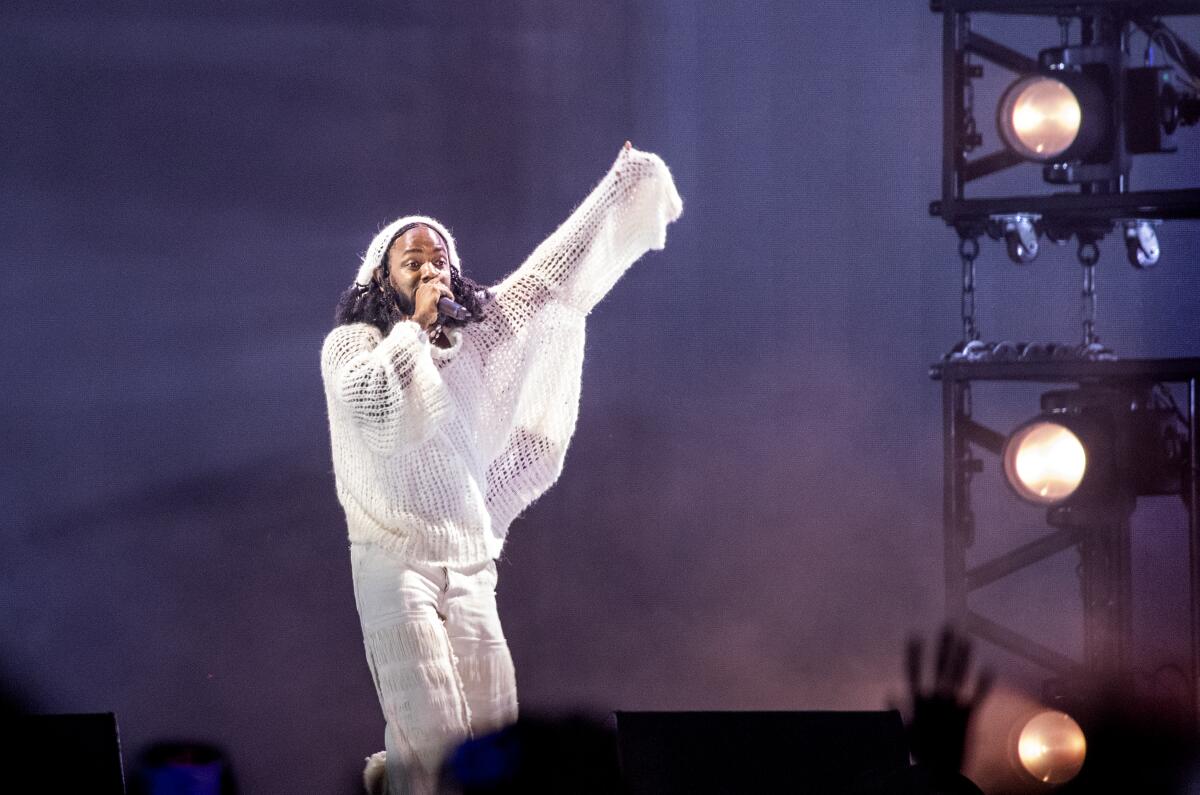

The approach made sense for the festival setting, in which audiences crave recognizable hits, yet Lamar — something of a scene elder at a moment when hip-hop has strayed from intricately plotted wordplay — brought new dramatic and emotional flair to his well-loved oldies. Dressed all in white, in an oversized crocheted sweater and loose-fitting cap that gave him a prophetic, Bob Marley-ish air, he performed alongside several distinct dance crews: a troupe of men in dark red suits, a group of ballerinas and a dozen or so children, including one boy who threatened to steal the show as he swiveled around a chair during “Swimming Pools (Drank).”

As the civil lawsuits against Travis Scott and Live Nation pile up, legal experts say that Scott could also face arrest for his part in the Astroworld tragedy.

Lamar himself did more dancing than he has in the past, suggesting (if not quite acting out) the narratives of entrapment and release that course through many of his songs. In “M.A.A.D City,” about the cyclical nature of gang warfare, he scampered playfully among the kids before they gave way to the men in suits, now equipped with flashlights that evoked a police raid; in the tender yet hard-nosed “Loyalty,” Lamar did a kind of pas de deux with a female dancer whose long braids swung behind her.

Throughout the show the performers were backed by strong visuals: scenes of everyday Black life in Compton during “Money Trees,” Lamar’s silhouette filled with images of fire and water for “Element,” a live-video recreation of “Damn’s” stark album cover in “DNA.” For the swaggering “Humble,” a stagehand with a Steadicam hovered behind Lamar, feeding images of the rapper’s view of the crowd to the giant screen — until Lamar turned around, that is, and growled the rest of the song down the camera’s lens.

No band was visible onstage, but the music sounded live, with frequent instrumental elaborations on Lamar’s recorded arrangements, as in “Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe,” which had a wild horn outro, and “Loyalty,” whose bridge got a lush ’70s-soul makeover. The rubbery bass line in “King Kunta,” from 2015’s “To Pimp a Butterfly” — which Lamar’s preface framed as a meditation on the connections between Compton and South Africa — was somehow funkier than on the album; “I,” built on the ebullient groove from the Isley Brothers’ “That Lady,” kept hurtling forward.

Lamar’s rapping was crisp even at its densest, which made songs like “DNA” and “The Blacker the Berry” — knotty, impassioned explorations of African American identity — go over like pop anthems. For “Alright,” which is a pop anthem, the audience more or less took over for the MC, shouting every lyric as he rocked his body to the propulsive beat.

Many Britney Spears supporters hope the justice system will dig deeper on the larger apparatus they say enabled her father in controlling her estate for 13 years.

Hearing his best-known songs in this rat-a-tat fashion demonstrated how solidly Lamar has established himself as a generational figure, especially to Southern Californians, who regard him as both an inheritor and an interrogator of the West Coast tradition pioneered by the likes of Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg, both of whom he’ll appear with at the Super Bowl.

Yet the historically rooted sound and the intellectual ambition of his music — not to mention his impulse toward community-building — also set him apart from rappers only a few years younger than he is, including most of those at Day N Vegas. Hip-hop in 2021 often drills down into personal experience; Lamar seeks to illuminate the cultural and political systems that shape those experiences, which in a funny twist can make him seem like a man on his own.

Before his farewell promise of a quick return, Lamar brought out his cousin Baby Keem (who’s set to perform his own set at Day N Vegas) to do their “Family Ties” and “Range Brothers.” Then he finished on a contemplative note with a dreamy “Love” and “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst,” during which his many dancers slowly assembled into a striking, family-portrait-like tableau. Taking a seat in the middle of the group, Lamar crossed his legs calmly as he delivered the song’s complicated thoughts on kinship and legacy — an artist long since grown comfortable with the demand for his talent.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.