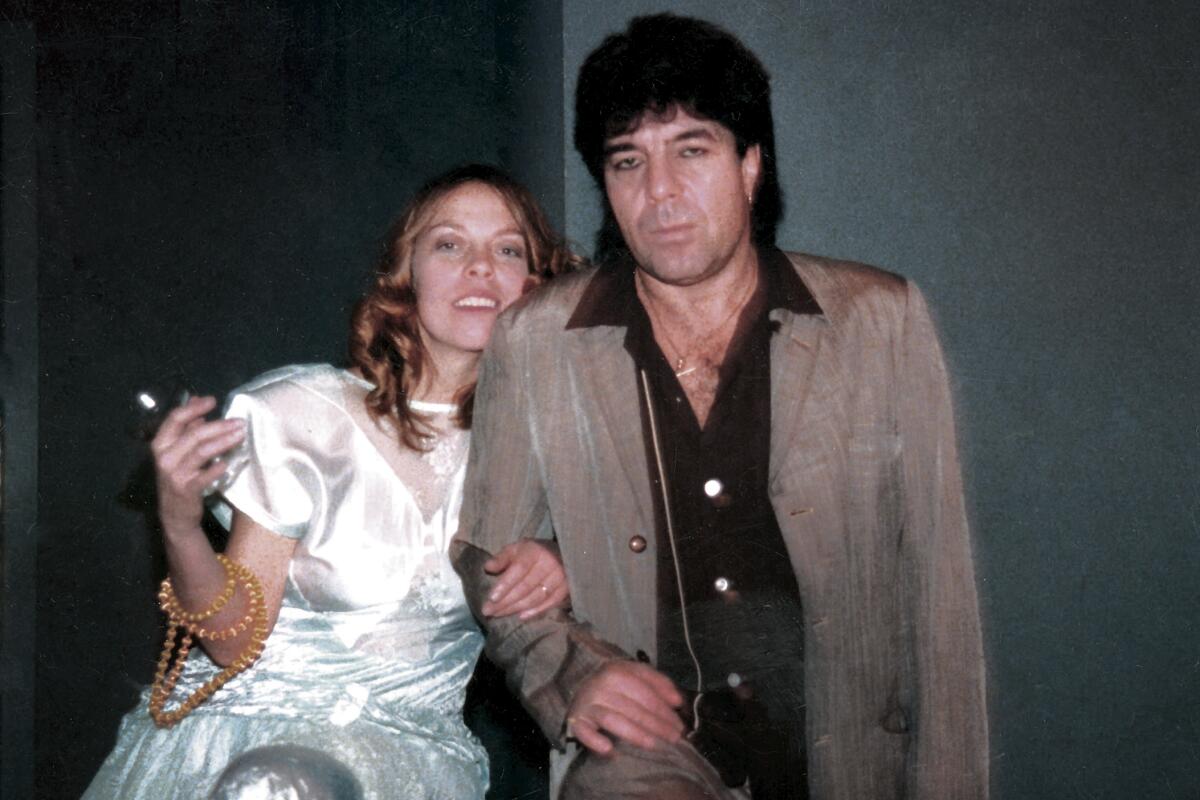

Rickie Lee Jones remembers Chuck E. Weiss: ‘He was a Svengali to Tom Waits and everyone who knew him’

Musician and bandleader Chuck E. Weiss died on July 19 at 76, after an extended battle with cancer. Here, Rickie Lee Jones, who famously name-checked Weiss on her breakthrough 1979 hit “Chuck E.’s in Love,” recalls days and nights spent prowling L.A.’s hipster demimonde with Weiss and his partner-in-crime, Tom Waits.

Chuck Weiss was Tom Waits’ sidekick for so many years that when I met him I could not tell them apart. It was as if he had always been there. They were two of the most charismatic characters Hollywood had seen in decades and without them I think the entire street of Santa Monica Boulevard would have collapsed. They were hipsters long before the word was overrun by very unhipster writers, held it up like hitchhikers hoping for a ride out of their own skins, or like that dilapidated Hollywood sign of 1978, trying to remind people there was still great music to learn from in a time when all anyone wanted to do was get a shag haircut and forget about learning anything. Chuck was a digger of culture and more than once brought up great nuggets of Black music for Waits to mine.

Chuck and Tom shared Lucky Strike cigarettes, they leaned against the wall the exact same way, and on occasion they even shared the same dame who, stumbling out of Waits’ kitchen, ended up in Weiss’ basement.

Forever known as the subject of Rickie Lee Jones’ breakthrough hit ‘Chuck E.’s in Love,’ Weiss was a running mate of Tom Waits and a co-owner of the Viper Room.

Besides those girls, there was little Waits actually shared. Chuck got the scraps, and that’s the truth. And don’t get me wrong, he was not entitled to share Tom’s ascension. Tom had carved his own place among the poets and passersby and was not about to give up one phone number or one poetry night slot.

But there was a love there, something between them, a symbiotic relationship like the fish who cleans the shark. When I met them, and it was them I met, not him, or him, Chuck was the wiser of the two, and given the chance might have been the kinder, but he had already found his way to barbiturates and fooled himself into thinking it was a better way to go than heroin. It certainly did not shake up the A&R guys the way skag did, but the damage was every bit as bad — addicting, debilitating and a sad substitute for respect and love.

Still, he was a Svengali to Waits, and everyone who knew him. While Chuck’s music might have seemed derivative, what he passed on to others was as authentic as it got, at least for people who never experienced the real thing. The music he played live was the music he loved. And for the white kids lining up outside the Central on Sunset Blvd., this was as close to the Black clubs of Cleveland and Memphis as they were ever gonna get.

When “Chuck E.’s in Love” came out in ‘79, Weiss was catapulted to fame far above his mentor’s. He began to imagine having a music career of his own, which he really had not considered before and had no right to. He could not sing, he did not play an instrument. But he could make up a rhyme along the lines of Waits, and eventually so many musicians in town wanted to play with him because if Waits liked him, he must be good, and because, well, he was Chuck E.

The Central gave Chuck legitimacy as a musician, and he kept his job there for a decade or so. It became the place to go in the ‘80s. Actors who wished they were Black or at the very least real guitar players sat in with Chuck regularly. River Phoenix died out in front of the place. Inside the club, Chuck was making paths into Black music that would become as meaningful as any other musician in L.A. for one reason — he had the capacity to engage an audience that would never have been engaged otherwise.

When TikTok gave surprising new life to Surf Curse’s 2013 song “Freaks,” the band had just denied sexual misconduct allegations that nearly ended its career.

I saw him there a few times with Spyder, his sax player and Katey Sagal’s old flame. Chuck and Spyder both wore their bathrobes onstage, though I’m pretty sure Spyder did it first. Chuck just did better. His song selection was outstanding, and great horn players showed up to get paid very little and be seen on stage with Chuck. Chuck E., the spokesperson, became bigger than the product.

Eventually he wrote a few interesting titles, nothing special but true to his love of ‘40s and ‘50s R&B. What he nurtured, what he harvested, were the roots of rock ‘n’ roll. Waits loved it. I loved it. Everybody loved it.

When “Chuck E.’s in Love” passed from the heavens and faded into the “I hate that song” desert, from which it still has not really recovered, he and I became estranged, and everyone fell away from everyone. Waits left, the brief Camelot of our street corner jive ended. I had made fiction of us, made heroes of very unheroic people. But I’m glad I did.

That great hit song was something of a beautiful rogue elephant who, after escaping from the zoo, remained hidden in the Hollywood Hills somewhere near Argyle. Occasionally someone would spot her, still stained with pink and purple paint, the paisley patterns fading down her legs, a vague and beautiful defiance in her eye. She disappeared around the time they tore down Chuck’s old apartment under Waits’ house.

I still hear her, though, on the radio, making this strange noise that almost sounds like singing.

Rickie Lee Jones is a musician and author of the memoir “Last Chance Texaco: Chronicles of an American Troubadour.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.