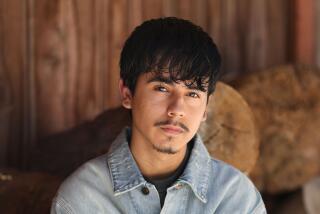

The sublime sadness of Mexican indie star Ed Maverick

At the twilight of his teen years, Mexican singer-songwriter Ed Maverick was well on his way to becoming a bonafide rock star.

Born Eduardo Hernández Saucedo in the sleepy town of Delicias, in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua, the now-20-year-old Maverick never planned to lead Mexico’s new generation of indie-rock romantics. He was only 17 when he began releasing his lo-fi, norteño-inflected love ballads on Soundcloud; it was after the release of “Acurrucar” and “Fuentes de Ortiz” that Universal Music Mexico started to ring his cellphone while he was in class.

By 2018, Maverick had dropped out of high school and released his first mixtape on the major label: “Mix Pa Llorar En Tu Cuarto” (A Mix for Crying in Your Bedroom). After releasing an EP called “Transiciones” in 2019, he rapidly became Mexico’s most viral artist on Spotify — then began to establish a sizable following among Latinos in the U.S., especially in Southern California, where he shared the stage with rising stars Cuco and Ambar Lucid at the Viva! Pomona music festival. By 2020, Maverick was due for an expansive tour across the U.S., where he would have made his very first Coachella appearance.

Christian Nodal and Gera MX’s ‘Botella Tras Botella’ (Bottle After Bottle) has become a viral hit, topping Spotify and breaking big in L.A.

That was all before the pandemic.

“As a general rule, I try not to hope for things,” he tells The Times from his childhood bedroom in Delicias. He instinctively rolls his eyes, in disbelief at the sheer melodrama of his own words, but the sentiment still stands.

“If you’re holding out for something to happen, and it never does, that’s just a bummer,” he explains of his career strategy. “It’s better to expect nothing, so that when something cool happens, you can really appreciate it.”

After spending nearly two years shuttling from city to city on tour, he moved to Mexico City in 2019, where he began to write and record his new full-length debut, “Eduardo,” released April 30 — a reintroduction to the artist, not as the sullen teen with shaggy hair in his eyes but as a more self-possessed young man.

In writing what would become his new album, Maverick mined the work of late Argentine artists like Luis Alberto Spinetta and Gustavo Cerati, prolific singer-songwriters who translated their surrealist visions into timeless rock. Maverick also pulled from the arty, cut-and-paste soul of Frank Ocean, the freak-folk of Animal Collective and the 2018 Arctic Monkeys record, “Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino,” which he admires for its “textured world of sound.”

Grammy-winning producer and keyboardist Milo Froideval and engineer Ricardo Acasuso helped Maverick piece together his official debut while self-isolating in Argentina and New York, respectively, a process that lent itself to the album’s roving spirit. The opening track, “Hola, ¿Como Estás?” — a three-word phrase amounting to “Hi, how are you?”— is the most cursory social interaction one can have in any language, but for Maverick, those three words carried more power than he’d ever anticipated in a time of mass isolation. During the pandemic, the world felt vaster than it did before; “Eduardo” resonates like a haunting satellite message from a faraway planet.

“I was not in a stable place before [the pandemic],” says Maverick. “As soon as I’d meet someone, I’d have to say goodbye.”

In the first area concert since the pandemic, and the first at SoFi Stadium, Foo Fighters, Jennifer Lopez and Prince Harry appear at “Vax Live.”

True to his adopted English name, Maverick, he was an outsider well before he became a hometown hero. At 14, Maverick began playing local bars and weddings as a drummer in regional Mexican bands with his friends, “but I didn’t like being in a band that much,” he says. At home, he taught himself guitar by emulating English indie rocker Jake Bugg and punky Mexican singer-songwriter Juan Cirerol, as well as the traditional corridos and cumbias he grew up with. The prickly strumming of his guitar heroes and the steely-eyed emotionalism of his norteño heritage planted the seeds for Maverick to grow his own rapturous desert soundscapes, which sprawl outward and spiral into the cosmos.

“There is this rugged kind of masculinity [to] corridos,” he explains, “but there’s also a sensitivity there. … It’s not about being aggressive. It’s about being strong.”

Thanks to the internet, Maverick began experiencing the greatest success of his life, but soon his music and his appearance were being mocked online, and strangers even began sending nasty messages about his mother. People also sifted through tweets he wrote in high school, including a homophobic statement, for which Maverick has since expressed regret. Of many negative epithets thrown at him, the phrase “mop head” — a common refrain among old rocker types, aimed at Maverick’s messy bowl cut — is one of the few that are safe for print.

In 2019, during his first show in New York, Maverick broke down crying on stage; he had been test-driving the new “Eduardo” cut, “Gente,” a reflection on how the internet breeds some of humanity’s worst impulses.

“I did not know what the hell to do with that attention; I was a child then,” he says, his brows now visibly furrowed beneath freshly trimmed black curls. Maverick now takes pains to avoid the internet and only posts to social media to promote his album. (Though he still counts on his small circle of friends to share funny memes in private.)

“Why does that attention really matter?” he asks. “Why did I need it? I just wanted people to listen to my music, but I struggled with this idea that ... maybe I’m not the one who should be fronting a project like this. I needed to be more responsible.”

“Eddie is 20 going on 40,” says the artist-producer Wet Baes, or Andrés Jaime, who plays the drums on several tracks in “Eduardo.” Working with Maverick, says Jaime, “is like an eternal game of intellectual ping-pong. I admire his style of songwriting; it is so raw and simple but, at the same time, aligned with the collective unconscious of all people.”

On “Eduardo’s” dusky folk-gone-hip-hop single “Niño,” Maverick sings, “Life is a beast that is killing me slowly,” his voice weathered well beyond his years. With a crashing trap beat, Mexican rapper Muelas de Gallo interjects coolly as the tattooed proverbial angel on Maverick’s shoulder. “What is life about if there is no pain?” he spits in Spanish, “Everything is fine, calm, breathe / Let it fall.”

The horizon seems to brighten in “Nos Queda Mucho Dolor Por Recorrer” (We Have a Lot of Pain to Go Through), a rambling, psychedelic ranchera written with fellow Mexican sad boy Daniel Quién. But the emotional turning point of the album for Maverick happened while recording a lush sound collage he eventually titled “¿Por Qué Lloras?” (Why Are You Crying?). As if trapped in a bathysphere, a man sobs discreetly beneath the hissing of rain sounds and warbling synths — the man, professes Maverick, was himself.

“I just couldn’t figure out why I was living [in] the same loop, over and over,” says Maverick.

“Crying is a vital part of that cycle,” he continues. “I say this like a friend to whoever needs to hear it. ... When you cry after the pain, you feel more pleasant after. You feel like yourself.”

As coronavirus restrictions vary from city to city, Maverick is still finalizing plans to tour “Eduardo” in the United States later this year. Until then, in the quiet of Delicias, he continues to ride out the uncertainty of the pandemic and, more generally, his life.

“The album represents a cycle that I will be living all my life,” he reflects. “You learn things, yes, but you have to let yourself hurt about things too. I had to let myself hurt … to come back stronger.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.