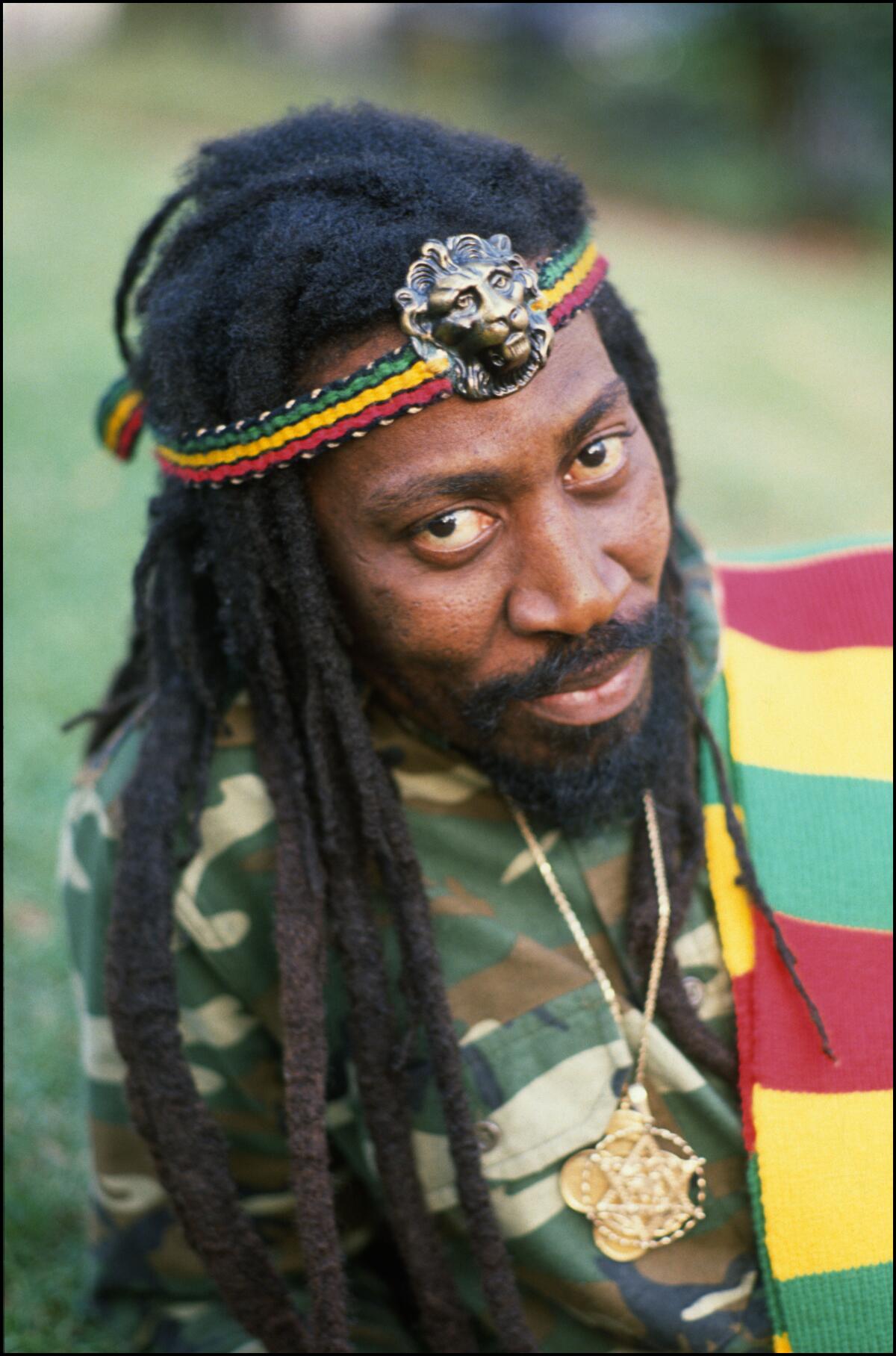

Reggae icon Bunny Wailer, co-founder of famed group the Wailers, dies at 73

Bunny Wailer, one of the most influential singers in reggae music history, died Tuesday at age 73.

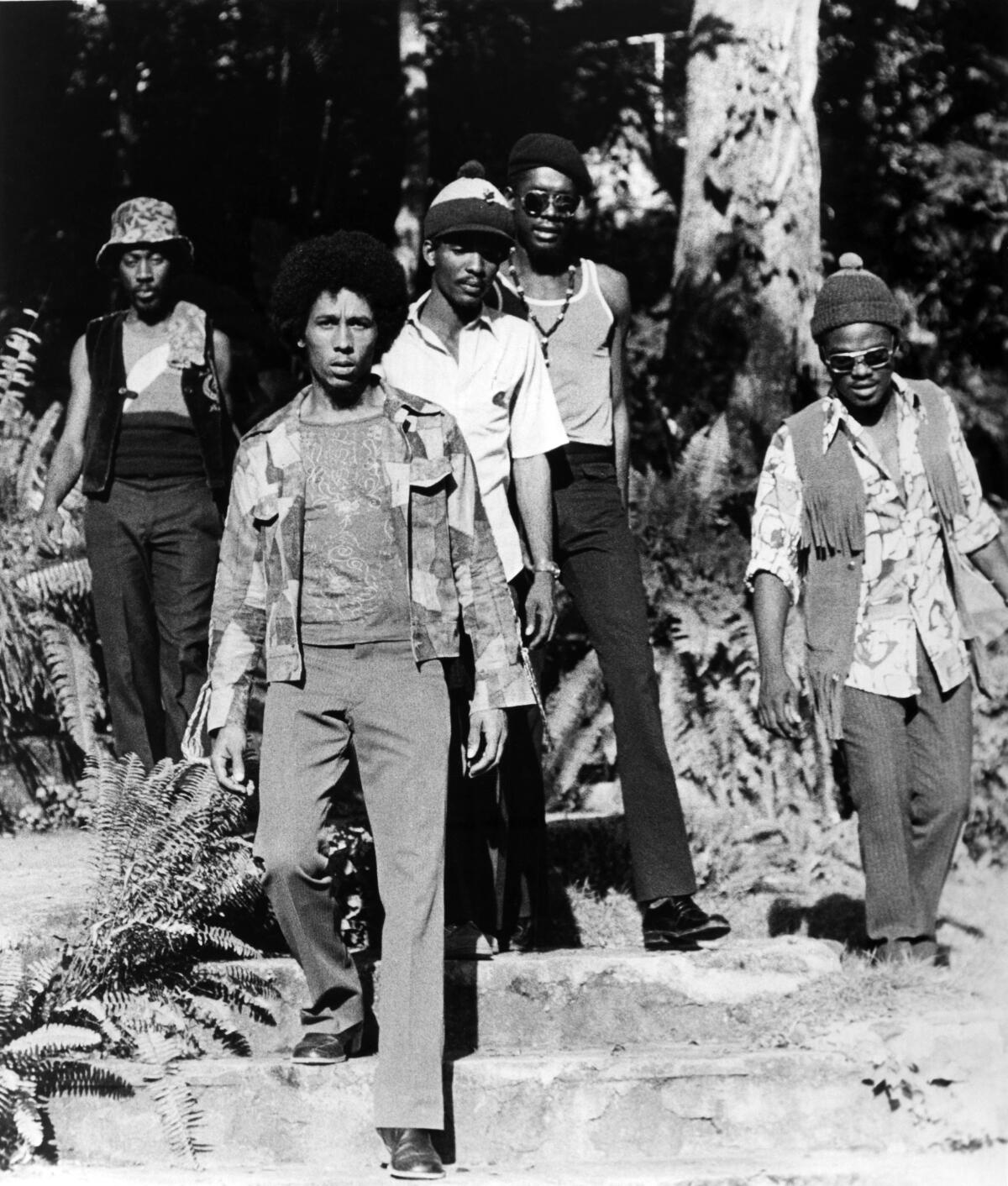

Along with a young Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, the artist born Neville O’Riley Livingston co-founded vocal trio the Wailers, who played a crucial role in transforming early 1960s ska music into rocksteady and ultimately reggae.

Wailer’s death was confirmed by his manager, according to the Associated Press. The cause of the death was not immediately known. Jamaican newspapers reported that he had a stroke about a year ago.

Best known for his work in songs including “Simmer Down,” “Rude Boy,” “Get Up, Stand Up,” “I Shot the Sheriff,” “Stir It Up,” “Blackheart Man” and dozens more, Wailer’s Zen-like approach to music creation, to say nothing of his vocal tone, helped manifest a new language focused on groove and vibe. After leaving the Wailers in 1973, Wailer carried on as a solo artist, releasing more than two dozen studio albums.

“The United States vs. Billie Holiday” tells the tale of the FBI’s targeting of the jazz singer, whose “Strange Fruit” became a protest anthem.

An epochal moment in Caribbean cultural history occurred by happenstance when in 1963, Wailer moved into the same Kingston apartment complex as a young Marley. Originally a quintet, the Wailers were schooled in harmony singing by influential vocalist Joe Higgs. A year later the group released “Simmer Down,” a bouncy dance song that became a building block for a movement.

Wailers, Downpresser

By 1965 the Wailers had pared down to the trio of Wailer, Marley and Tosh and continued to make hits. Whether with three or five members, early Wailers singles offer a wild lesson in the borderless power of music. In the early 1960s, the island had reason to dance. It had finally achieved independence from British colonial rule.

Still, cultural and familial ties endured. Simultaneously, Jamaica’s location in the Caribbean allowed it access to New Orleans radio stations, some of which could be heard as far south as Kingston. Coupled with the influence of calypso music broadcast from Trinidad and Tobago, the Wailers and peers including the Heptones, the Maytals, Ken Boothe and Delroy Wilson homed in on tones and textures that combined those and homegrown elements to light up dance floors. Not just in Kingston, but London too.

The Wailers’ “I Need You” was a candlelit ska-and-soul song that reverberated with as much intensity as anything in Phil Spector’s catalog. “Rude Boy,” about the booming generation of young toughs running the streets of Kingston, has since become shorthand for “ska fan.” Although Marley made the song famous on his smash album “Live!,” the trio version of “One Love” rolls with a more uptempo R&B rhythm.

In 1969, the Wailers — who, in general, harmonized with Tosh singing low, Marley in the middle and Wailer wailing up top — entered Lee “Scratch” Perry’s Black Ark studio to create “Downpresser,” a riff on the song “Sinnerman.” Slowing ska and rocksteady’s tempos by a third, it and the early dub remix B-side, “Downpresser Version,” helped transform Kingston’s club and sound-system scene.

The albums that followed, “Catch a Fire” and “Burnin’,” blew up in Jamaica, then in England, Europe and America. Co-produced by Marley and Island Records’ Chris Blackwell, they also solidified Marley as the “leader” of the group. Were it not for those Wailers albums, fans of all nationalities, races and fraternity-house affiliation would never have sung along, forearm-sized spliff in hand, to “I Shot the Sheriff,” “Get Up, Stand Up” and “One Love.”

The Wailers embarked on international tours to spread the message, which was both explicitly political and fueled by a desire for universal peace. Their success fomented a 1970s roots reggae explosion, one that informed hits by non-reggae artists of the era including Stevie Wonder, the Rolling Stones and the Clash.

When Wailer left the Wailers, he cited frustration with touring — he didn’t like to fly — and Marley’s increasingly dominant role. A longtime Rastafarian who put his religion above all else, he spent his creative life in a vast compound and received callers when he desired.

“Music is based on inspiration and if you’re in an environment where you are up and down, here and there, that’s how your music is going to sound,” Wailer told The Times in 1986. “People get taken away in getting themselves to be a star and that is a different thing from getting yourself to be a good writer, musician, producer and arranger.”

Wailer chased that goal across his life. He wrote and produced all of the tracks on his first solo endeavor, 1976’s “Blackheart Man.” A sonically dynamic roots reggae album that informed Kingston’s first-generation dancehall records, it added curious studio elements including backward-tracked guitars, haunting church organ, electric piano and Wailer’s own percussion playing. Conjuring images of reincarnated souls, armageddon, oppression, conviction and devotion, the artist maneuvered between protest songs and anthems on the power of dancing, moving and loving.

His 1979 album “Roots Radics Rockers Reggae” found him teaming with the Roots Radics, a tight Jamaican for-hire band. For Wailer’s 1980 album, he drew from his past. Called “Bunny Wailer Sings the Wailers,” it was recorded at Wailer’s longtime Kingston studio of choice, Harry Js, with Wailer singing work written by Marley and Tosh.

Unfortunately, many of his best records are unavailable on major streaming services. The three albums for which Wailer won Grammy awards in the 1990s — “Time Will Tell: A Tribute to Bob Marley,” “Crucial! Roots Classics” and “Hall of Fame: Tribute to Bob Marley’s 50th Anniversary” — are absent from Spotify and Apple Music.

Wailer was the last of the original Wailers. He was preceded in death by Marley, who died of complications from cancer in 1981; and Tosh, who was murdered in Kingston in 1987.

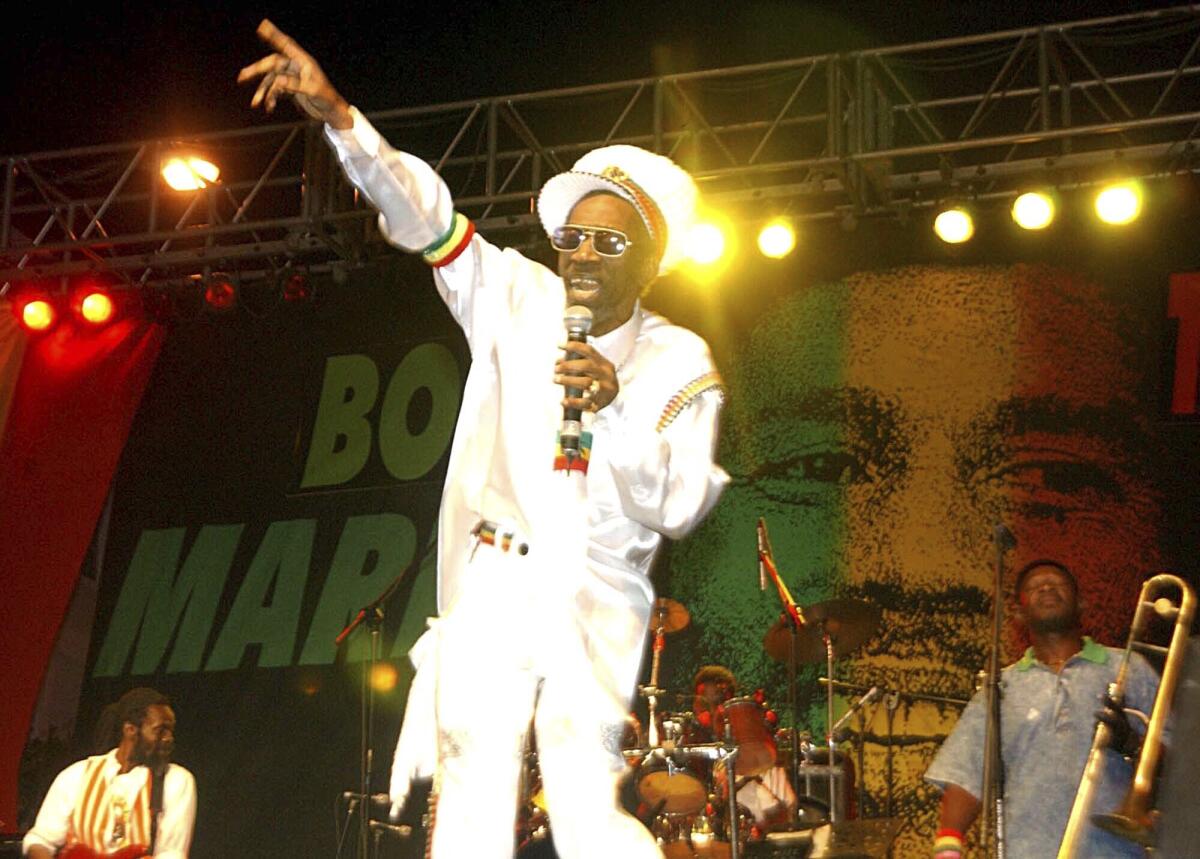

As the decades passed, Wailer pushed through his discomfort with air travel and started touring. Crowds enthusiastically greeted him.

Asked what had changed by the NME in 1984, Wailer said that “if you’re not doing it for the people it doesn’t make sense.” Adding that reggae artists should be in front of crowds, he concluded that his role was to “soothe the stress and the tension by letting them know that their feelings are shared. It’s like sharing a weight — that’s what reggae does.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.