Harold Budd, ambient composer and Eno collaborator, dies of COVID-19 complications at 84

The minimalist composer and musician Harold Budd, whom collaborator Brian Eno once described as being “a great abstract painter trapped in the body of a musician,” died on Tuesday of complications from COVID-19. He was 84.

His death was confirmed by his manager, Steve Takaki.

Starting in the 1960s, the Los Angeles native drew from Minimalism, free jazz and beatless ambient music — even if he disliked the last term — to craft meditative work that moved like a Pacific breeze.

From homegrown jazz to furious punk to raw hip-hop recorded from prison, these 10 albums highlight L.A.’s creative spirit in a hard-scrabble year for musicians.

Across a 50-year creative run, Budd worked with artists including the visionary musician and producer Eno, Scottish dream-pop group the Cocteau Twins, XTC’s Andy Partridge, producer and musician Daniel Lanois, British synth-pop innovator John Foxx and French producer-musician Hector Zazou. Earlier this year, Budd’s solo work helped score the HBO drama “I Know This Much Is True.”

Living mostly in Southern California — with a career-establishing few years in London — Budd composed, taught and performed works that from the start rejected the jarring, busy approach to then-contemporary experimental music. Such work of the time “seemed self-congratulatory, and for a small cadre of snobs, and I refused to go on with it,” he told L.A. Record.

Harold Budd and Brian Eno, “First Light”

Instead, starting in the early 1970s, “I purposely tried to create music that was so sweet and pretty and decorative that it would positively upset and revolt the avant-garde, whose ugly sounds had by now become a new orthodoxy.” As with one of his avowed inspirations, painter Mark Rothko, Budd explored the way in which subtle tonal shifts affected perception and mood.

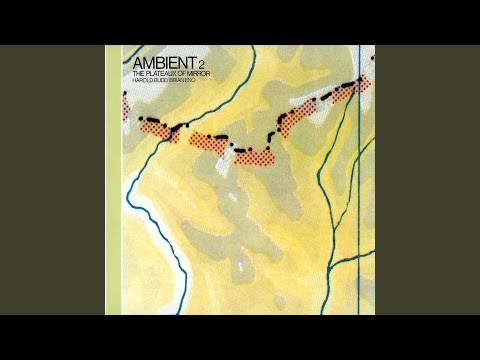

His two albums recorded with Eno, 1980’s “Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror” and 1984’s “The Pearl” (which also features Lanois), are considered pinnacles of the ambient movement and helped establish Budd’s reputation, one that was bolstered by a project he made soon thereafter with members of the Cocteau Twins. Called “The Moon and the Melodies,” it was issued in 1986 by the hip independent imprint 4AD and introduced Budd’s name to a new generation of outsiders.

Budd’s approach expanded on works such as “Abandoned Cities” (1984) to include darker, more foreboding tones, but he never veered into the ugly or confrontational.

Born in 1936 in central Los Angeles to Harold and Dorothy Budd and raised at the edge of the Mojave Desert in Victorville, Budd served in the Army alongside future saxophone skronker Albert Ayler. Both shared an affinity for post-bop experimentation, a connection they discovered while playing together in the military band. Budd’s first instrument was a drum kit, and for a while he made his living playing Los Angeles nightclubs. By the time he started taking classes at L.A. City College he’d been “everything from cowboy to mailman,” he told the composer Carl Stone during a 1998 interview on KPFK. Unlike Ayler, who seemed to revel in injecting chaos into his music, Budd followed cues drawn from nights spent at gigs by more meditative artists like Chet Baker and Pharoah Sanders.

Harold Budd and Robin Guthrie, “After Dark.”

Budd’s first released piece, “The Oak of the Golden Dreams,” was recorded in 1970 on an early model Buchla modular synthesizer at the California Institute of the Arts. Sounding like some primal bloop of the computer age, the work harnessed the instrument’s ability to endlessly sustain drone notes while zapping out scattered, occasionally melodic bolts of midrange texture.

Soon landing a teaching job at CalArts, which was then in Burbank, Budd through the early 1970s devoted his time to teaching while composing in off-hours. His life changed in the mid-1970s with an out-of-the-blue phone call from a fan, Eno, who had heard a recording of one of his pieces. “I owe Eno everything, OK? That’s the end of that,” Budd said with blunt appreciation, of that first conversation with his future collaborator. Eno invited him to London, and Budd didn’t think twice. “I was plucked from the tree, and suddenly I had flowered. I was just waiting. I couldn’t do it on my own. I didn’t know anything.”

He knew his muse, though, and with Eno making his sonic arguments for a more tranquil music with his own series of ambient releases, Budd eased his way into the movement to become one of its standard-bearers. He devoted himself to piano, keyboards and guitar, texturing his recorded work with blurry drone tones until sounds seem to bleed together.

His aesthetic vibrated on a distinctively Pacific Coast frequency. If the sound of California cool jazz as presented by players such as Baker and Gerry Mulligan was informed by a gentler, more stoned approach than the New York center, Budd took that approach to the extreme. “The Pavilion of Dreams,” released in 1978, was a patiently mesmerizing whoosh of gentle sound, featuring saxophone, synthesizer and a willful absence of percussion.

The between-genre approach was so alien to performance spaces and audiences of the era that many critics weren’t having it. One reviewer for The Times in 1985 seemed to completely miss the point, dismissively writing of one performance that Budd “arranged pots of exotic plants and a hanging brass gong and surrounded them with electronically altered keyboard music that sound[ed] like the score for an arty movie.”

Budd was continually composing, releasing both solo albums and collaborations every few years for the rest of his life. His 1988 album for Eno’s Opal Records, “The White Arcades,” was powered by Budd’s “soft pedal” piano technique, which employed one of the instrument’s foot pedals to “soften” the notes while subtly changing their tones. “The Room,” his 2000 album for Atlantic Records, was a conceptually linked project in which he composed distinct pieces for imaginary spaces such as “The Candied Room” and “The Room of Forgotten Children.”

Budd announced his retirement from music in 2004, but apparently he didn’t consult with his creative spirit. In a review of Budd’s short-lived “farewell performance” with Jon Gibson at REDCAT in downtown Los Angeles, The Times characterized Budd as “a willfully mysterious character, musically and personally. He has gone missing from the local scene for long stretches, making each Budd sighting something special.”

A few years later, though, he returned with “Perhaps” and continued to compose for the rest of his life. Along the way, Budd issued a series of albums with Cocteau Twins’ Robin Guthrie; the most recent, “Another Flower,” was released just last week. According to his manager Takaki, Budd had recently finished composing a series of two dozen string quartets.

In his later years, the Pasadena-based artist was the opposite of mysterious, eagerly discussing his work with journalists, podcasters and fellow composers. In Budd’s 2016 conversation with L.A. Record he explored the ways in which he devoted his life to music.

Citing an epiphany he had while listening to a Pharoah Sanders album — “It wasn’t fancy, it was just there” — he explained, “I wanted to be responsible for music that would change your life ... Because it changed my life, and it’s all I could do.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.